Racism appears to be as Canadian as hockey. Does this mean that racism has been with us forever, in all parts of the world, that it is somehow part of our genetic makeup? What can we learn from the responses to racism that have arisen over time?

A pessimistic view would say that racism is part of human nature and there is nothing that can be done to eradicate it. A liberal view sees racism as mere ignorance, which can be educated out of existence. A reformist view sees racism as a result of bad policy that can be fixed through an electoral strategy and better legislation.

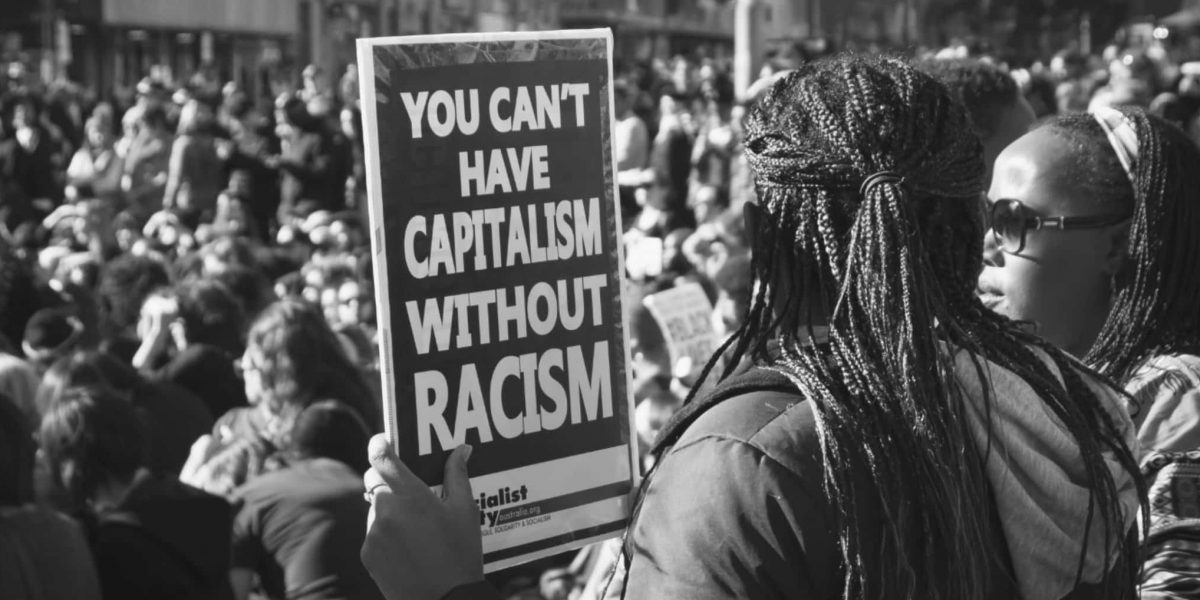

But in a socialist view, racism is not just the result of bad individuals or bad policies: it is central to the way that capitalism emerged and perpetuates itself. As a result racism is not timeless and can be eliminated along with capitalism, but this is only possible through a revolutionary strategy that centers anti-racism.

Modern racism

Women’s oppression dates to the emergence of class societies thousands of years ago (and was absent from egalitarian Indigenous societies prior to recent colonization). But racism, which intersects with other forms of oppression, is a relatively modern phenomenon—first manifested with the trade of slaves from Africa to the West Indies and the territories that would become Canada and the US. This expansion was critical to, not simply coincidental with, the emergence of capitalism as a world system in the seventeenth century, and for its subsequent development as the dominant social and economic system.

There was xenophobia (fear of strangers) before capitalism, but this is not racism. In early self-contained villages, someone from another village might be defined as a “foreigner”. But this distinction was applied to all outsiders and reflected an attitude to someone who is merely different, not biologically inferior, as is the claim of racism.

There was military conquest and slavery before capitalism, but this is not racism. The Roman Empire invaded territory they defined as “barbarian”, regardless of the ethnic makeup of the inhabitants. There were slaves of all skin colours, the transition from freedom to slavery was fluid rather than fixed, and at one time there was a Black emperor.

There was Anti-Semitism before capitalism, but the early form was based on religious and not racial grounds. In the Middle Ages in Europe, the main form of social oppression was on the basis of religion, specifically Catholic vs. non-Catholic. Many groups, therefore, who were not Catholic, felt the wrath of the Catholic Church. An important difference, then, between racism and earlier forms of social oppression is that, with racism, there is no possibility of a person changing their race in the same way that one could change one’s religion, or even become educated so as not be considered “a barbarian”, in order to escape persecution. Anti-Semitism as we have come to know it today, based on the racial notion of being Jewish, did not appear until the nineteenth century, when the Jew was no longer treated as a religious outsider but as a member of a biologically inferior race. As the Jewish political theorist Hannah Arendt notes: “Jews had been able to escape from Judaism(religion) into conversion; from Jewishness(race) there was no escape.”

What this means, therefore, is that racial differences were invented relatively recently. What is striking about slave and feudal societies of pre-capitalist Europe is the absence of ideologies and practices which excluded and subordinated a particular group on the grounds of their inherent inferiority. There was no ideology of biologically distinct races, because it has no scientific basis. As the scientists Richard Lewontin, Steven Rose and Leon Kamin explain in their book Not in our Genes: Biology, Ideology and Human Nature, most genetic variations are between individuals within the same local population, tribe or nation:

“This means that the genetic variation between one Spaniard and another, or between one Masai and another, is 85% of all human genetic variation, while only 15% is accounted for by breaking up people into groups…Any use of racial categories must take its justifications from some other source than biology.” This source was the emerging socioeconomic system of capitalism.

Capitalist slavery

The enslavement of African people brought to the West Indies and the Americas differed radically from its ancient predecessor. Slavery in ancient Europe served to support the leisured lifestyle of a landed ruling class. Slavery as it developed during European colonization of the Americas, on the other hand, was an essential element in what Marx called “the primitive accumulation of capital”, the concentration of wealth in the hands of a new capitalist class oriented on production for profit. As Marx explained in Capital,

“The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signalised the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production…The treasures captured outside Europe by undisguised looting, enslavement, and murder, floated back to the mother-country and were there turned into capital.”

In was in this environment that racism was formed, as an attempt to justify the most appalling and inhuman treatment of Black people in the slave trade and the plantation slavery of the New World – in the service of the greatest accumulations of material wealth the world had until then seen. As the Guyanese historian Walter Rodney explained in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, anti-Black racism was intertwined with capitalism and accompanied Indigenous genocide:

“Occasionally, it is mistakenly held that Europeans enslaved Africans for racist reasons. European planters and miners enslaved Africans for economic reasons, so that their labour power could be exploited. Indeed, it would have been impossible to open up the New World and to use it as a constant generator of wealth, had it not been for African labour. There were no other alternatives: the American (Indian) population was virtually wiped out and Europe’s population was too small for settlement overseas at that time. Then, having become utterly dependent on African labour, Europeans at home and abroad found it necessary to rationalise that exploitation in racist terms as well. Oppression follows logically from exploitation, so as to guarantee the latter. Oppression of African people on purely racial grounds accompanied, strengthened and became indistinguishable from oppression for economic reasons.”

This was a gradual process. The first wave of colonization was driven by xenophobia, military conquest and Christian conversion, and the first sources of labour included Indigenous and Black slaves as well as white indentured servants. But Indigenous people were on their own land, which they defended against genocidal attacks, and there were insufficient white workers for both indentured servitude in the Americas and for industrializing Europe. The alternative was the exploitation of Black slaves, along with an ideology that shifted from religion to race. There was a possibility that slaves could convert to Christianity, much as many Jews (including Karl Marx’s father) had done to avoid discrimination and persecution. But the new ideology of racism was different: it was permanent and inherited, so it provided a justification for enslaving certain people, along with their children and their children’s children. As with Indigenous genocide, this was not just an American institution but was the foundation of the Canadian state. As historian Afua Cooper reminds us: “Slavery was the dominant condition of life for Black people in this country for well over 200 years. So we have been enslaved for longer than we have been free.”

Racism’s ideological origin was thus as a justification for the trans-Atlantic slave trade beginning in the seventeenth century, and it continued as a central method for capitalist expansion. This was important both to justify the inhuman exploitation of Black people, and to divide the solidarity between Black slaves and white indentured servants. It was only after a series of revolts that racist laws came into effect to divide Black from white workers. This dual purpose of racism—to increase the exploitation of racialized workers and to divide the working class—continued even after slavery ended. As Angela Davis explained in Women, Race and Class,

“The colonization of the Southern economy by capitalists from the North gave lynching its most vigourous impulse. If Black people, by means of terror and violence, could remain the most brutally exploited group within the swelling ranks of the working class, the capitalists could enjoy a double advantage. Extra profits would result from the superexploitation of Black labor, while white workers’ hostilities toward their employer would be defused.”

The ideology of empire

By the mid-nineteenth century racism became the ideology of empire. It was paternalistic, “scientific”, and nationalistic.

Christ taught “Thou shalt not steal, Thou shalt do no murder”. So Christendom had to justify robbery and murder, and developed the theory of the inferiority of Black people. The mass murder, robbery and rape carried out in Africa, Asia and the West Indies were written up as “civilizing missions” and a paternalistic “white man’s burden.”

Racist “science” developed when anthropologists measuring bones, particularly skulls, started with an assumption of the superiority of European people. Darwin’s Origins of the Species appeared in 1859, and he demonstrated that Europeans and Africans belonged to the same species, all descendants from apes, thus disproving the old racist belief. But this was conveniently ignored by the “Social Darwinists” who believed that whites were “naturally” superior.

The third characteristic of nineteenth century imperialism was its link with nationhood. The view that a nation was a body of people related in blood, with a common history and common destiny was a powerful means of mobilizing the masses in times of war. Comte de Bobineau wrote Essay on the Inequality of Races, expressing hope that the future of the world was with the Teutons, whom he called “Aryan”. Although he could only find a handful of pure Aryans in Germany, and that Germany was no more Aryan than a number of other countries, Gobineau’s theories were later taken up by Hitler.

Labour migration

The “double advantage” described by Davis remains central to capitalism, both within countries and for movements of workers between countries. Capitalist expansion goes through periodic booms and busts, with rising and falling need for labour. Labour migration is therefore essential to the capitalist system. The purpose of immigration policy is to regulate the flow of labour across borders and to control the workers themselves. States use border policies to create precarious working conditions, stoke racist divisions and exclude migrants from health and social services. Capitalists then use precarious working conditions to superexploit migrant workers and pit them against other workers and drive down wages. Racism is both a permanent feature of capitalism, and a malleable ideology that can shift over time according to the needs of capitalism. As Marx wrote, at a time when Irish people weren’t considered white,

“Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself. He cherishes religious, social, and national prejudices against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the ‘poor whites’ to the Blacks in the former slave states of the USA. The Irishman pays him back with interest in his own money. He sees in the English worker both the accomplice and the stupid tool of the English rulers in Ireland. This antagonism is artificially kept alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organisation. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power. And the latter is quite aware of this.”

In other words, while bosses and workers alike can perpetuate racism, its origins and ongoing role is to exploit and divide workers. So all workers need to fight racism, including the racism coming from the bosses and the racism that infects fellow workers.

Racism, resistance and revolution

As long as anti-Black racism, as a systemic ideology developed under capitalism, has existed, so too has there been resistance—from the slave revolution in Haiti that began in the late 18th century, to the abolition movement in the 19th century, to the Civil Rights and Black Power movements in the 20th century, to Black Lives Matter today.

Because racism is central to capitalism, anti-racism crucial for all movements—for decent work and paid sick days, which are disproportionately denied to racialized and migrant workers; to climate justice, which is intertwined with Indigenous liberation; to abolition, which shows that divesting from police and prisons could empower real community safety.

The ultimate solution to racism is to end the system which created and sustains it and other forms of oppression, namely capitalism. This cannot be left to the NDP, to trade union bureaucrats, to race relations or human rights agencies. Real power lies in mobilizing rank and file activists in the working class and in other movements whose struggles take on the system. This can turn the anger, the despair, the sense of powerlessness that gets turned into scapegoating, into anger that is directed against the government and against the corporate ruling class. We can show that working people—Black, white, Asian, immigrant and Indigenous—have the same interests.

Not only do we need socialism to eventually eliminate racism and other forms of oppression, we first need working class unity in order to reach the goal of socialism. Racist ideology is pervasive and affects us all, which requires a constant struggle against racist divisions within the working class. Struggle is the arena where racist ideas are challenged and break down, and through the process of building working class unity we can raise workers’ confidence about a better world. A socialist society based on our common human needs, and not on the need for profit by a few at the top, is the only way we will see an end to racism and a society which no longer has a need to have us divided from one another. As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor concludes in From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation,

“Solidarity it not just an option; it is crucial…Success or failure are contingent on whether or not working people see themselves as brothers and sisters whose liberation in inextricably bound together. Solidarity is standing in unity with people even when you have not personally experienced their particular oppression. The reality is that as long as capitalism exists, material and ideological pressures push white workers to be racist and all workers to hold each other in general suspicion. But there are moments of struggle when the mutual interests are laid bare, and when the suspicion is finally turned in the other direction—at the plutocrats who live well while the rest of us suffer. The key question is whether or not in those moments of struggle a coherent political analysis of society, oppression, and exploitation can be articulated that makes sense of the world we live in, but that also champions the vision of a different kind of society—and a way to get there.”

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate