“Far from being marginal to the struggles of Black people, socialists have always been at the centre of those movements–from the struggle to save the Scottsboro Boys in the 1930s, to Bayard Rustin’s role in organizing the 1963 March on Washington, to the Black Panther Party’s organizing against police brutality.” — Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation

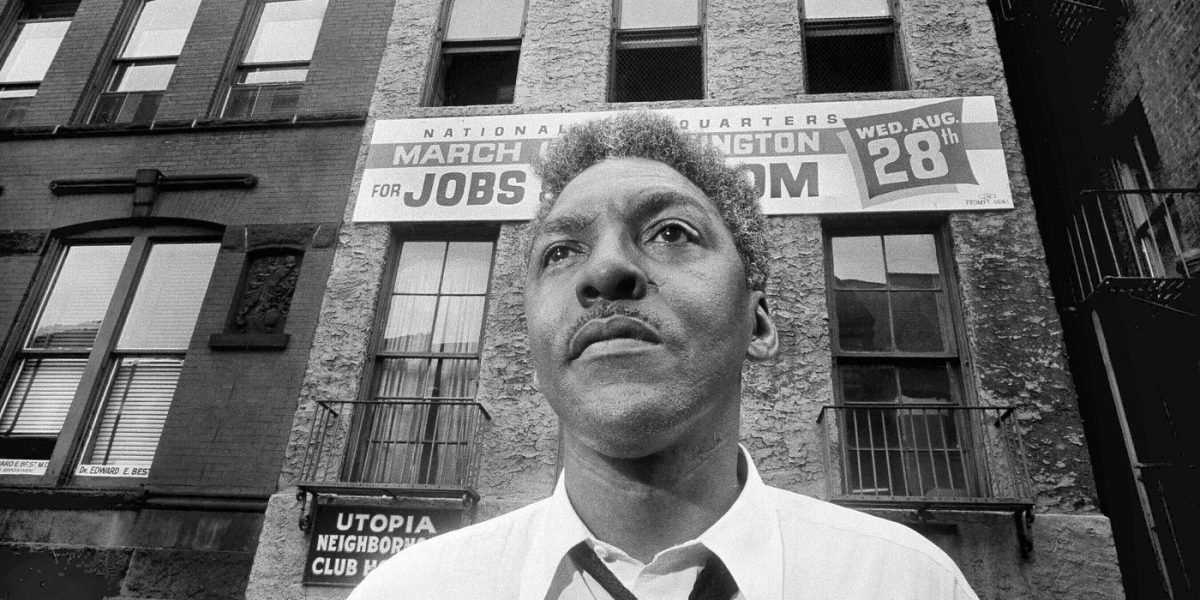

August 28 is the anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington, where Martin Luther’s King delivered his famous “I have a dream” speech. But the march’s main organizer, Bayard Rustin, has been largely written out of history—for being gay, a socialist, and a war resister. Now, as movements for social and economic equality rise again, his life and politics have a new relevance.

From Depression to Civil Rights

Rustin was born in 1912 to a Quaker family active in the early NAACP, where he derived his pacifism and quest for justice. He developed his class politics and organizing when he moved to Harlem in the 1930s and joined the Communist Party. The Depression disproportionately affected Black Americans through job losses, evictions, racist violence, and racism within the trade union movement. The Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA) helped lead multi-racial campaigns against evictions, job losses and lynchings (including the first march on Washington in 1933, as part of the Scottsoboro campaign), and to organize Black workers in the North and the South who had been ignored by the American Federation of Labour. As Rustin recalled, “I learned many of the most important things I learned about organizing and writing clearly from my experience as a communist.”

But when the increasingly Stalinized CPUSA abruptly switched from opposing WWII to supporting it over civil rights, Rustin left along with many others. Instead he worked with the Black trade union leader A Philip Randolph and the white Christian pacifist AJ Muste. Randolph was a socialist who had organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1925, the first Black trade union the in the US. Together they began organizing a march on Washington in 1941 to pressure Roosevelt to ban discrimination against Black workers in defense industries and Black workers in uniform during WWII. Randolph called off the march when Roosevelt banned discrimination in defence industries, and another threat of a march on Washington in 1948 pushed Truman to desegregate the armed forces. Rustin went to jail for refusing to fight in WWII, and then organized with the War Resisters League.

With Muste, he worked with the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). Along with Ella Baker—another unsung hero of the civil rights movement—they organized multi-racial civil disobedience to Jim Crow. The Civil Rights movement is presented as a spontaneous outburst, but was built on years of prior experience. As Rustin recalled: “That period of 8 years of continuously doing this prepared for the 1960s revolution. I do not believe Montgomery would have been possible nor successful except for the long experience people had about reading about sitting in buses and getting arrested, so that people had become used to hearing this.”

When the Montgomery bus boycott began, Rustin brought his two decades of experience and contacts to advise its new leader, Martin Luther King. His account humanizes King and explains how he was not a born leader but developed through the course of the struggle:

“The fact of the matter is, when I got to Montgomery, Dr. King had very limited notions about how a nonviolent protest should be carried out. He had not been prepared for the job either tactically, strategically, or in his understanding of nonviolence. The glorious thing is that he came to a profoundly deep understanding of nonviolence through the struggle itself, and through reading and discussions which he had in the process of carrying on the protest.”

Rustin helped King launch the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to advocate mass action and provide a counter-weight to the legal strategy of the NAACP; similarly, Ella Baker helped launch the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the student wing of the civil right movement. Rustin also organized a youth rally in Washington that inspired future Black leaders. As Stokely Carmichael recalled, “The first time I saw Bayard Rustin I said ‘that’s what I want to be’. When I saw him I said, ‘that’s it, a black man who’s a socialist, that’s the real answer’. He was like superman. At that moment in time, he appeared to be the revolution, the most revolutionary man.”

Brother outsider

But Rustin was repeatedly marginalized, both in wider society and within the movements. In Jim Crow America he was Black, during the height of McCarthyism he was a socialist and a war resister, and a generation before Stonewall he was openly gay. He was beaten by police for sitting in a white-only section of a bus, beaten for being gay and Black while in jail for resisting the war, and arrested for being gay. Homophobia within the movement and resistance to his politics also undermined his work. Muste fired him and King dropped him as an advisor. As Rustin recalled, “Martin Luther King, with whom I worked very closely, became very distressed when a number of the ministers working for him wanted him to dismiss me from his staff because of my homosexuality.” When Rustin and King planned to march on the Democratic Convention, Harlem’s Democratic Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr called Rustin an “immoral element” in the civil rights movement and drove a wedge between him and King.

Rustin’s FBI file called him an “ardent pacifist and is considered to be the foremost Negro exponent of the doctrine of ‘passive resistance.’” But he was sidelined and written out of history. As his biographer explained in Lost Prophet: the Life and Times of Bayard Rustin:

“The arrest trailed Rustin for many years afterwards. It severely restricted the public roles he was allowed to assume. Though he fought his way back from the sidelines, he did so at a price. As both the peace and civil rights movements grew dramatically over the next decade, as a philosophy of nonviolence became familiar to millions of Americans, Rustin’s influence was everywhere. Yet he remained always in the background, his figure shadowy and blurred, his importance masked. At any moment, his sexual history might erupt into consciousness. Sometimes it happened through the design of enemies to the causes for which he fought, sometimes through the machinations of personal rivals, sometimes through the nervous anxieties of movement comrades. But underneath it all was the unexamined, because as yet unnamed, homophobia that permeated mid-century American society.”

Jobs and Freedom

In 1962 Rustin debated Malcolm X and outlined his strategy of multi-racial non-violence, both to challenge those in power and to fight racism within the ranks of the working class: “As we follow this form of mass action and strategic non-violence, we will not only put pressure on the government but we will put pressure on other groups which ought by their nature to be allied with us. And they will have to stand up and be counted in their own interest.”

Then in 1963 Randolph and Rustin planned their third march on Washington to push for civil rights legislation. The march brought together the major civil rights organizations (NAACP, SCLC, CORE, SNCC, the National Council of Negro Women, and the Urban League) as well as trade unions. While the AFL-CIO didn’t endorse it, the United Auto Workers was one of the main organizers and there was also support from steelworkers, ladies garment workers, packinghouse workers, electrical workers, and labour councils. Segregationist Senator Strom Thurmond tried by undermine the march by attacking Rustin for being gay, socialist and a war resister, but this time the other civil rights leaders came to his defence. The march mobilized a quarter of a million people and helped win civil rights.

But as Rustin anticipated, the end of legal discrimination did not mean social and economic equality. The goal of the march was not only to win civil rights to set the stage for the next phase of the movement for racial and economic justice. It was called the March for Jobs and Freedom, with a strategy to put Black liberation at the heart of the movement for economic justice. As Rustin explained:

“Integration in the fields of education, housing, transportation and public accommodation will be of limited extent and duration as long as fundamental economic inequality along racial lines persists…When a racial disparity in unemployment has been firmly established in the course of a century, the change-over to ‘equal opportunities’…does not wipe out the cumulative handicaps of the negro worker… The dynamic that has motivated negroes to withstand with courage and dignity the intimidation and violence they have endured in their own struggle against racism may now be the catalyst which mobilizes all workers behind demands for a broad and fundamental program of economic justice.”

From protest to politics?

But Rustin’s uncompromising multiracial non-violence, which sustained him from the 1930s to the 1950s, became a barrier between him and new movements in the 1960s. While he had inspired Black Power leaders he criticized them and the ghetto uprisings of the late 1960s, as well as the National Liberation Front in Vietnam. Instead, Rustin called for a shift “from protest to politics”, with a focus on the trade union bureaucracy and the Democrats, and supported President Johnson while the Vietnam war raged on. A generation later we can assess the results of this shift. As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor explained:

“Rustin was suggesting that the shift into formal politics marked a sign of political maturity and could deliver much more substantive change to black communities than protest alone. He had in mind an expansive social-democratic program pursued by a fresh wave of politicians. (There were barely a hundred black elected officials in 1964.) We got the politicians (ten years after Rustin’s call, there were several hundred black elected officials) — culminating in the 2008 election of Barack Obama — but not the welfare state… Of the many problems in US society Black Lives Matter has exposed, the sharp division within black politics stands out. The political rancor partly reflected a generational divide, but it also showed a schism between the class anger of black workers and the class optimism of a tiny black elite.”

Black workers matter

While Rustin shifted from radical to moderate, King broke with him other civil rights leaders and spoke out against the Vietnam War and the “giant triplets of racism, militarism, and economic exploitation.” As Rustin’s biographer put it, “the pupil had surpassed the teacher”. King planned a Poor People’s March on Washington, and went to support 1,300 Black sanitation workers on strike, saying that “you are reminding, not only Memphis, but you are reminding the nation that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages”. Mainstream history has caricatured King as a simple dreamer and frozen his politics in 1963. But it was King who condemned the war and supported Black workers striking for higher wages and unionization, where he was assassinated on April 4, 1968.

A generation later are new movements against anti-Black racism and other forms of oppression, carrying on Rustin’s legacy. Whereas homophobia and sexism within the Civil Rights Movement marginalized Rustin and Baker, Black Lives Matter is led by Black women and centers Black trans and queer voices. A generation later there are new movements for economic justice like the Fight for $15, which are also led by Black and racialized women.

In 2017 the Fight for $15 and the Movement for Black Lives joined together in a national protest on April 4: “Nearly 50 years ago, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated while standing with striking sanitation workers in Memphis fighting for The Dream of fair pay and racial justice…On April 4, we’re carrying on that dream – because economic and racial justice are two sides of the same coin. You can’t have one without the other.” This convergence has continued through the pandemic. Following Rustin’s vision of Black liberation as a catalyst for economic justice for all workers, the Strike for Black lives mobilized in 160 cities across the US on July 20. As it explained, “Justice for Black communities, with an unequivocal declaration that Black Lives Matter, is a necessary first step to winning justice for all workers. To win higher wages, better jobs, and Unions for All, we must ensure that Black workers can build economic power.”

Similarly in Canada there are movements for Black liberation and defunding the police, and for higher wages and paid sick days. As human rights lawyer Anthony Morgan writes, these are not separate issues but two sides of the same coin:

“I believe now is the time to revisit, reform and or reintroduce stronger employment equity legislation. The root of almost every mass movement, and the source of so much social unrest, is economic exclusion—a feeling of being devalued, of not belonging. Black and other racialized people in Canada were already discriminated against in the workforce before the pandemic. They are now overrepresented in the lower-paid and precarious frontline jobs that pose the highest risk of contracting COVID-19. The feeling of social exclusion is acute among far too many Black populations in Canada. It’s in conditions like these that pernicious police-community relations thrive. So, if we really want to make Black Lives Matter, we have to make Black Jobs Matter too.”

On August 29 join the day of action for paid sick days and for defunding the police.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate