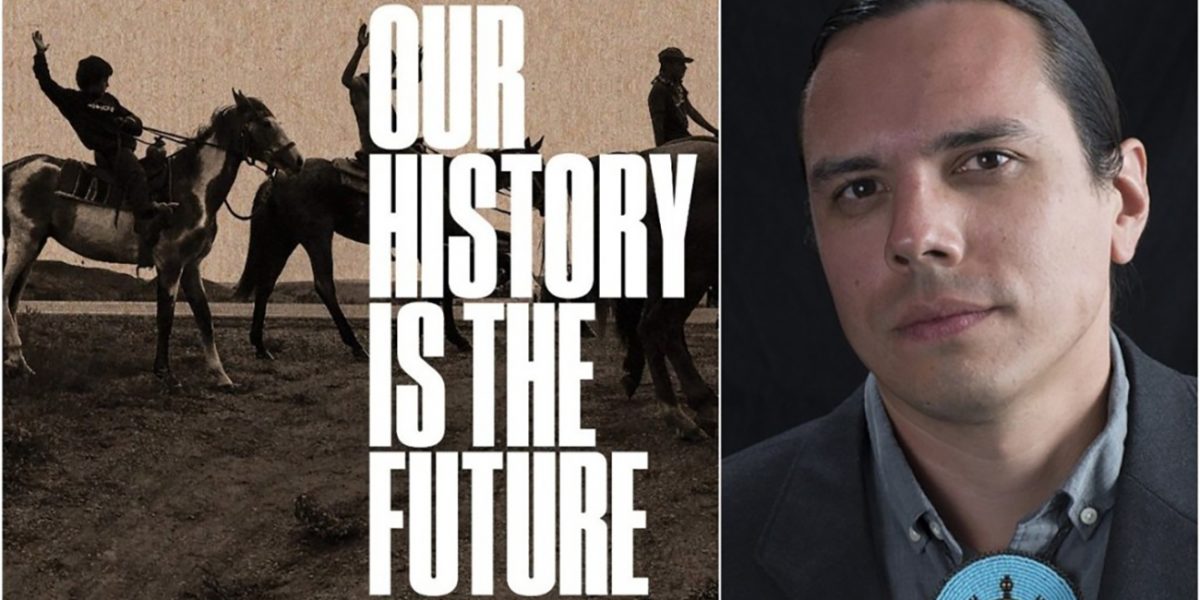

The resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) at Standing Rock was one of the most highly publicized stories of Indigenous-led resistance to the global fossil fuel industry. Indigenous water protectors defending their lands against heavily militarized police sent a powerful message across North America that Indigenous peoples will not stand idly by as their lands are desecrated for profit. In Our History is the Future, Lakota historian Nick Estes challenges the perception that these protests were a spontaneous modern phenomenon. He instead powerfully situates them in their historical context as the newest manifestation of resistance by the Oceti Sakowin peoples against the never-ending U.S. invasion of their lands.

The Oceti Sakowin are a federation of seven nations consisting of Lakota, Nakota and Dakota speaking peoples. Throughout this book Estes thoroughly and accessibly details how the invasion of their lands is part of the ongoing structure of settler-colonialism that aims to eliminate Indigenous ways of life.

Settler colonialism and capital accumulation

A central argument in this book is that the U.S. settler state’s ongoing efforts to eliminate Oceti Sakowin and other Indigenous nations is because they serve as barriers to capitalist accumulation, which is antithetical to their ways of life. In the second chapter Estes details how their lives as self-determining people were centred on principles of mutual solidarity and kinship. These values required economic and political customs that focused on collective well being instead private property and exploitation. Their social structures where women played prominent leadership roles in community and economic decision-making were at odds with patriarchal relations integral to the capitalist system. Land and non-human life such as Mni Sose (water) and Pte Oyate (Buffalo) were and continue to be viewed as kinship relations rather than exploitable commodities. These explanations help readers understand how the various eras of settler-colonial invasion and occupation described in following chapters are part of an ongoing violent imposition of a foreign capitalist system.

The third chapter that focuses on the fur-trade wars of the 18th century outlines various brutal and tragic methods the U.S. military used to impose colonial and capitalist structures. This includes the systematically planned annihilation of much of the plains Buffalo population to force Oceti Sakowin peoples into dependency on the emerging U.S. capitalist economy. This continues in the next chapter where Estes describes how dams created under the 1944 Pick-Sloan plan led to further mass displacement of Oceti Sakowin communities and the elimination of much of their remaining land-based economies. This demonstrates how post-war “prosperity” for the U.S. settler state was built at the expense of sovereign Indigenous nations, which Estes argues was mirrored in the 2008 revival of the oil economy.

Indigenous resistance

However, Estes is clear that the reason Oceti Sakowin nations have survived these ongoing attempts of elimination is because of their capacity to continuously resist. There are many examples throughout the book that demonstrate the creative ability of their resistance movements to shift between various tactics appropriate to their immediate conditions. A prominent example is how their fight for a de-colonial future was revived in the form of the non-violent Ghost Dance movement in the 1890s, in the wake of the defeat of their decades long armed resistance to the U.S. military.

Estes describes this array of shifting tactics as part of the continuously growing revolutionary theories of Oceti Sakowin and other Indigenous nations. Marxist readers should note that Estes, himself a Marxist, heavily foregrounds these Indigenous theoretical and tactical contributions to revolutionary thought. This sends an important message that anti-capitalist and anti-colonial programs on stolen Indigenous lands cannot overlook the unique revolutionary ideas of Indigenous nations.

It also must be noted that Estes presents this history through an Indigenous feminist lens. While popular male Oceti Sakowin leaders are given prominent mention in these resistance struggles, he highlights the contributions of female and two-spirit leadership in both contemporary and past movements. This is presented as a crucial part of building a future for Oceti Sakowin peoples that is free from the hetero-patriarchal structures that have been imposed on them by colonization.

This historical context effectively makes the point that the NoDAPL protests were far more than just a single-issue campaign against one pipeline. They are evidence that Indigenous resistance to capitalism and colonialism is not a remnant of the past, but an ongoing struggle that will continue to re-emerge as long as their lands are occupied by the United States. However, Estes does not limit his conception of Indigenous resistance to a negation of colonial oppression. His descriptions of day-to-day life at the Sacred Stone and Oceti Sakowin camps detail the power of the 400 Indigenous nations and allies who came together to form a community governed through the caretaking and kinship relationships that colonialism has tried to erase. Estes describes these moments as glimpses of a future where Indigenous nations take control over their own lands in order to build a world beyond the capitalist and colonial systems that are destroying the planet.

Important lessons for contemporary movements

While the book describes experiences relevant to Indigenous nations across North America, it is primarily a history of the resistance of Oceti Sakowin peoples. This is a reminder that all Indigenous nations have their own unique histories of pre-colonial life, experiences of settler-colonial genocide and anti-colonial resistance. Solidarity with Indigenous decolonization movements must be based in the recognition that they are all rooted in their unique national histories. Non-Indigenous peoples should take the effort to learn about the histories of the specific nations whose land they occupy if they desire to be serious allies in their struggles.

However, this local history is also placed within a firm internationalist lens. Estes describes U.S. settler-colonialism as form of territorial expansion that is closely related to global imperialism. The book contains important examples such as how the fur-trade wars in the 1800s informed U.S. military tactics in their later invasions of Vietnam and Iraq, as well as the ongoing U.S. support for Israeli occupation of Palestinian land. This analysis is complemented with examples of how anti-colonial and Black liberation movements around the world have acted in solidarity with Indigenous resistance movements in North America. This shows that a global system of imperialist domination can be most effectively challenged by international solidarity among colonized and oppressed peoples.

Settler readers must comprehend the fact that settler-colonialism has not exclusively been implemented by the ruling classes. Estes describes the early European peasants who encroached onto Oceti Sakowin lands to claim them as private property as part of the “vanguards of invasion.” There are various instances in which white settlers are shown to be both beneficiaries of and active participants in settler-colonial violence. While all settlers are inheritors of this dark legacy, Estes also recounts class-based alliances that can serve as examples for building solidarity. This includes the 1980 Black Hills alliance where members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) allied with white working-class people and farmers to oppose Uranium mining in the black hills. This is used to demonstrate how working-class settlers can build meaningful solidarity with Indigenous peoples by uniting under common interests to oppose corporate exploitation and protect the land they depend on for existence.

Though, as the final chapter shows, settlers cannot have an ethical connection to the land or its original peoples if it remains stolen. This is a reminder that talk of a just future in socialist and climate justice movements can only be genuine if they lead to stolen lands being returned to their Indigenous caretakers. While Estes says there is no clear path for how to move forward, he states that “whatever the answer may be, Indigenous peoples must lead the way. Our history and long traditions of Indigenous resistance provide possibilities for futures premised on justice.”

An example of this leadership is evident in the Indigenous socialist organization, The Red Nation, which Estes co-founded in 2014. They provide a preliminary outline for a radical program in their document, “Four Principles of the Red Deal.” The Red Deal builds off of popular Green New Deal proposals by ensuring that Indigenous liberation and anti-capitalism are centred, along with the reality that only mass movements from below can achieve radical change.

Our History is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance is published by Verso Books

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate