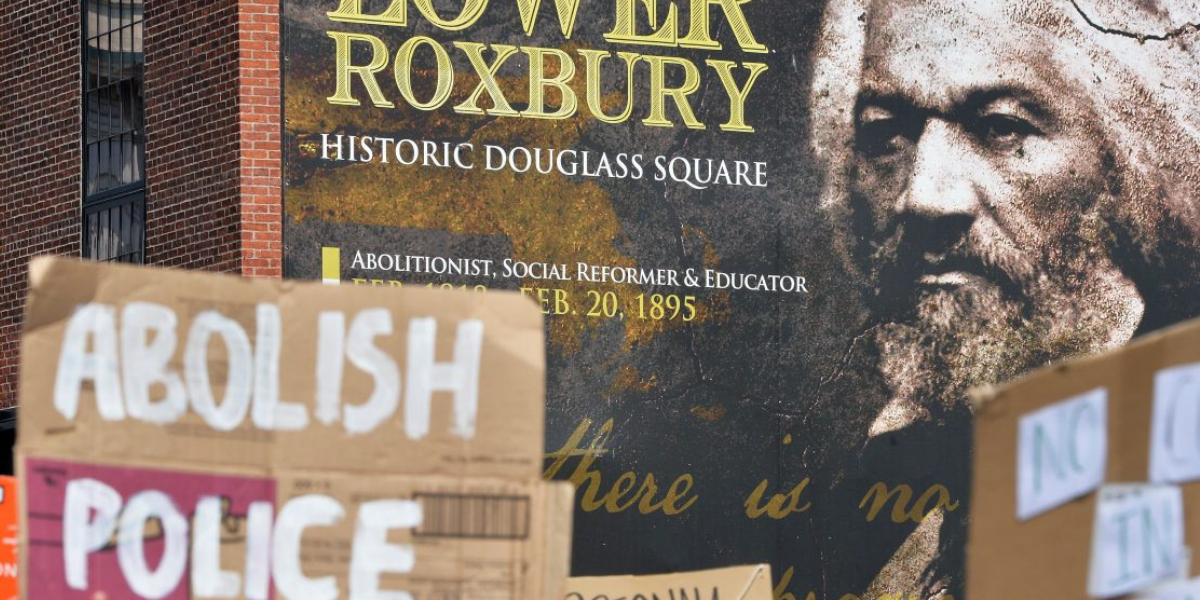

The renewed Black Lives Matter movement and efforts to defund the police that have blossomed since last summer’s global wave of racial justice protests has put the question of abolition back in the spotlight.

Frederick Douglass, the foremost abolitionist of 19th century America, waged a tireless struggle against the institution of slavey and white supremacy. His life and times were revolutionary in every sense of the word and contain valuable lessons for today.

From slavery to self-emancipation

Douglass was born enslaved in Maryland, most likely in 1818, and his childhood was full of the trauma that was unique to the institution of slavery. He never knew his father and only had a fleeting memory of his mother. In his autobiographies, he described his childhood as a world of “Eden-like” beauty and evil, a playground and a prison. At six years old he was separated from his grandmother and moved to the Wye plantation. Reflecting back on his childhood in 1855 he noted, “I was just as well aware of the unjust, unnatural, and murderous character of slavery, when I was nine years old, as I am now.”

At nine years old, he became property of the Auld family and was sent to Baltimore. It was here that Douglass began to learn to read and write. The Aulds discouraged Douglass’ reading, which caused Douglass to work even harder in secret to educate and teach himself. When he was a teenager Douglass was hired out to two plantations in the Chesapeake Bay area, forced to do brutal, back-breaking labour. But he mobilized his new found education to preach and organize his fellow slaves. After one escape plot was foiled, Douglass finally emancipated himself in 1838, heading north with his wife Anna Murray.

They ended up settling in the whaling town of New Bedford, Massachusetts. It was here that Douglass encountered and was eventually drawn into the organized abolitionist movement. Working as a labourer on the docks and other odd jobs in the new boomtown of New Bedford, Douglass eventually joined the small African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, where he started to preach to the small congregation.

But it was his chance encounter with a newspaper agent from William Garrison’s abolitionist Liberator that connected Douglass with the abolitionist movement. Douglass became an avid reader of the Liberator, noting “it took its place with me next to the bible.”

Abolitionist movement

Through the Liberator Douglass learned about the breadth of the abolitionist movement, its notable figures, its tactics and strategies, its debates and burning questions. He was enlivened by the fiery language of the paper and enthralled by the spirit of the movement. When the Liberator’s editor came to New Bedford in 1839, Douglass attended and was struck by the passion and fervour of the movement.

Douglass, now connected to the organized abolition movement, continued to give sermons at his local church about the evils of slavery by focusing on his powerful personal narrative. He also started to address white audiences in New Bedford via the Bristol County Anti-Slavery Society. In 1841 he attended the convention of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society and his address to the convention made such an impact he quickly became a featured speaker on the abolitionist circuit.

Douglass’ entry into the abolition movement coincided with a major schism developing in the movement over the question of strategy. Founded in 1830 by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan, the American Anti-Slavery Society was the preeminent organization of the abolition movement of its time. But Garrison’s strong moral stand against slavery developed into an anti-political crusade of disunionism. Garrison and his followers rejected any formal engagement with the U.S. political system. Instead, abolitionism for Garrison became a moral crusade, steeped in Christianity, preaching a revolution in moral values to move beyond the sin of slavery. Garrison’s strident and Christian anti-slavery rhetoric appealed to Douglass and many African Americans in the movement. But by the 1840s Garrison’s strategy was being questioned by some in the movement who looked to political advances to further the abolitionist cause.

Douglass was a devoted follower of Garrison’s wing of the movement and toured relentlessly with other abolitionist speakers across Northern states, facing violence and racism. About six years after his emancipation Douglass published his first of three autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. The book was popular and he soon toured Ireland, Scotland and England for nearly two years to promote it and forge international links for the abolitionist movement.

His experience outside of the U.S., where he was accepted and treated with a level of dignity he had never experienced in America, reinforced Douglass’ anger and contempt for American patriotism. As he noted in a speech soon after his return, “I have no love for America, as such. I have no patriotism. I have no country…The Institutions of this country do not know me, do not recognize me as a man, except as a piece of property.”

Revolutionary journalism and the shift from moralism to politics

Douglass returned to the lecture circuit, but soon decided to found his own newspaper, against the wishes of Garrison. Douglass thought it strategic to found a paper for and by Black people, and launched The North Star in 1848. A few years later Mary Ann Shadd, who corresponded with The North Star, became the first Black women newspaper publisher in North America when she launched The Provincial Freeman, an abolitionist newspaper in Ontario. Though both papers struggled financially, they helped build the Black abolitionist movement on both sides of the border.

As Douglass noted, The North Star “was the best school for me. It obliged me to think and read, it taught me to express my thoughts clearly.” The process of producing a weekly paper, responding to political events — like the Mexican American War, the formation of the Free Soil Party and the Fugitive Slave Act — helped clarify Douglass’ political positions in regards to the burning strategic questions facing the abolition movement. As Douglass wrote, “but for the responsibility of conducting a public journal, and the necessity imposed upon me of meeting opposite views from abolitionists outside of New England, I should in all probability have remained firm in my disunion views.”

Douglass increasingly rejected the political abstentionism of the Garrisonian wing of the abolition movement. Garrison advocated for moral suasion to win Northern voters to boycott elections and wait for a morally righteous government to supersede the institutions of tyranny. This was a strategy that was based on persuading the South to voluntarily end slavery in order to unite the union. Douglass realized that it would require force and a political movement, not simply moral suasion, to crush the institution of slavery.

In breaking with Garrison, Douglass looked to involve himself in political parties and movements that could advance the anti-slavery cause. He also now looked upon the Constitution as a potential weapon in this struggle. Douglass was keenly aware of the limitations and imperfections of political parties and legal tools in fighting slavery, but viewed them on balance as positive instruments.

The 1850s were a decade of increased political and social tensions over the question of slavery. The Fugitive Slave Act, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Dred Scott Decision and the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin radicalized the Northern opinion on the question. It was during this period that Douglass gave what is perhaps his most well-known speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, a searing indictment of the celebration of American “democracy” and “liberty”. His speech, which blended the secular and sacred to lay bare the hypocrisy of the United States, was greeted by rapturous applause by the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society and was quickly printed and distributed across the country.

Douglass was no mere commentator on these questions, he was a political activist helping to shape debates, from anti-slavery to women’s equality. As Angela Davis noted, “Frederick Douglass, the country’s leading Black abolitionist, was also the most prominent male advocate of women’s emancipation in his times.” His home in Rochester became a stop over for many escaped enslaved peoples on their way to Canada. Douglass crossed paths with the radical abolitionist John Brown in 1848, and their political relationship deepened through the 1850s. Douglass was attracted to Brown’s religious fervour and commitment to direct action, though the former sometimes balked at Brown’s lack of tactical acumen. Although Douglass did not take part in Brown’s attack on Harper’s Ferry, he was implicated and was forced to flee to Canada, where he remained exiled for six months.

War against white supremacy

By the mid 1850s Kansas become a bloody battleground over the expansion of the institution of slavery. The country was a powder keg. The Harper’s Ferry incident was a portent of the revolutionary changes on the horizon. The election of 1860 was the most contentious in U.S. history and Douglass supported the Republican party, which formed out of the Free Soil Party in 1854. The party contained abolitionists, but it was not an abolitionist party. Its opposition to slavery was rooted in the free labour doctrine. As Douglass noted, “The Republican Party is only negatively anti-slavery. It is opposed to the political power of slavery, rather than to slavery itself.” He worried that too many Republicans supported efforts to remove African-Americans from the United States, a persistent vein in the anti-slavery movement that Douglass long opposed.

Douglass had an initially positive view of Lincoln, thinking he was a radical who was committed to laying siege on the forces of slavery. But he disagreed with Lincoln and the majority of Republicans that slavery could only be ended constitutionally in places where it legally existed. Over the next three years, Douglass became a trenchant critic of Lincoln and the Republicans’ plodding and hesitant approach to the question of slavery.

The narrow election of Lincoln almost immediately plunged the country into crisis, in the North and South. Stock markets crashed, as northern businesses and workingmen fretted over the potential of disunion. Abolitionists became the target of political mobs in the North, and in late December South Carolina seceded from the union. Douglass, who initially feared that no great political upheaval would arise from the election, vacillated between optimism and pessimism during the three month secession crisis. He feared both that Lincoln and the Republicans would comprise the cause of abolition to avoid disunion, and that they would only wage a conflict over the status of the union not over the question of slavery itself.

This initial fear proved somewhat correct, as Lincoln and the North waged a war to unite the union. Lincoln, aiming to preserve the support of border states that permitted slavery like Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, and Kentucky, waged not a war of abolition but of preservation–even returning fugitive slaves to the South. Douglass worried that public support for abolition and for the war waned as the North’s war efforts went poorly. He aimed all his ire and vitriol on the southern Slave Power. He wanted to remind his readers and the North’s population that the Southern ruling class which defended slavery was treasonous and the ultimate enemy.

Douglass wanted the North to wage a total social war to eliminate the institution of slavery and strip the slavocracy of all vestiges of its power and wealth. He was an early proponent of Black enlistment in the army as both a way to advance the cause of abolition and as a military necessity. Slowly over the next two years the political and military tide shifted to Douglass’ position. By 1862 fugitive slaves were received into union lines and not turned back. This paved the way for the emancipation proclamation and the enlistment of Black soldiers into the union army.

This transformed the war and Douglass seized on the “paper proclamation” so it could “be made of iron, lead and fire”. Douglass organized and mobilized to encourage Black soldiers to enlist and agitated for the Union army to recruit Black soldiers. “Now the government has given authority to… black men to shoulder a musket and go down and kill white rebels.” While mainstream historians glorify Lincoln for “freeing the slaves” it was Black people themselves who fought for self-emancipation. As WEB Dubois later explained in his history of the Civil War, slaves leaving the Southern plantations en mass to join the Union army amounted to a general strike which shattered the Southern economy and its war effort.

At the time, Douglass well understood the revolutionary turn the war was taking and its implications for a post-Civil War future. As he remarked in a 1864 speech, “No war but an Abolition war; no peace but an Abolition peace; the black man a soldier in war, a laborer in peace; a voter at the South as well as at the North; America his permanent home and all Americans his fellow countryman.”

Post-Civil War

Douglass supported Lincoln in his reelection, understanding that what was at stake was the commitment to end the institution of slavery. Douglass was a critic of Lincoln but also a supporter, and came to appreciate his steadfastness in supporting abolition. The momentum saw the waging of a total war that ultimately laid waste to the Southern economy and the slavocracy.

The assassination of Lincoln and the ascension of Andrew Johnson to the presidency saw a great debate unleashed in the Republican party about the nature of Reconstruction. Douglass fell squarely on the radical wing of that debate, advocating for a strong federal government effort to enforce the rights of freed people in the South. But the first year of Reconstruction was marred by brutal racist violence. Douglass strongly supported efforts by Congress to seize control of Reconstruction and backed Grant in the 1868 election. Douglass supported the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments, outlawing slavery, guaranteeing citizenship and voting rights to all. But he was well aware that amendments without enforcement meant little and he was worried there was a growing indifference of white people to the plight of freedpeople.

In an 1875 speech Douglass worried over the fate of Reconstruction, noting “if war among whites brought peace and liberty to blacks, what will peace among whites bring?”. Indeed, it took another 95 years for the Voting Rights Act to enforce the 15th amendment, a victory won by the Civil Rights Movement. Douglass’ path forward was a mixture of inculcating self-reliance and education amongst freedpeople and demanding a strong enforcement of rights by the federal government. He did not look to the burgeoning union movement as a solution to collective power, in part because of his own experiences as a Black labourer being discriminated against by guilds and early unions. Anti-Black racism within unions and guilds of the time strictly enforced racial segregation, and it was only in the 1930s that a wave of strikes by Black workers desegregated unions and could then use them to advance their interests.

Douglass remained a critical but steadfast supporter of the Republican Party in the latter part of his life, despite its abandonment of Reconstruction and the interests of freedpeople. This provoked stern criticisms from other Black leaders such as John Mercer Langston. But Douglass could see no alternative to the Republican Party. Despite some of his political shortcomings in party politics, Douglass was firmly committed to supporting activist causes until his last days. He joined the antilynching crusade with radical journalist Ida B. Wells, was involved in campaigns to desegregate the World’s Fair in Chicago, and even served as an ambassador to Haiti.

Legacy

Douglass lived a revolutionary life. Born into slavery, he was self-emancipated and self-educated. For five and half decades he was a tireless activist and journalist, devoting his life to the abolition movement, the fight against white supremacy, and support for women’s equality. He was an internationalist, forming important links with radical abolitionists in the UK and in Germany via his longtime collaborator Ottilie Assing. He also supported Haiti, the first successful slave revolution, explaining to the 1893 World Fair that “We should not forget that the freedom you and I enjoy today is largely due to the brave stand taken by the black sons of Haiti ninety years ago…striking for their freedom, they struck for the freedom of every black man in the world.”

Douglass was an astute organizer, who effectively used the medium of the newspaper to build a network of radical abolitionists that could infuse, excite and persuade people into action. He used the press as a way to gauge the temperature of the movements and nation and to learn from and sharpen his politics.

Douglass understood the relationship between fighting for reforms and the necessity of revolution. Having been initially attracted to the ideas of moral suasion, he came to view that defeating the entrenched powers of the slavocracy would require more than moral arguments, it would require movements and self-activity. Abolitionism, to be successful, needed to wage a political fight, advocate for reforms, involve the masses, pressure the courts and politicians but with an eye of ratcheting up a political crisis and then boldly seizing it. Douglass stumped for politicians, but he never fully trusted them. He advocated for legal reforms but recognized that laws were one thing on paper and another thing in practice. He looked to the activity of the masses, to the enslaved Black people in the South and the Black and white workers in the North, to win and enforce abolition.

More than 200 years after Douglass was born into slavery, that institution is gone and civil rights have been won but systemic anti-Black racism remains. Any progress during the past 200 years has not been granted by benevolent governments from below but fought for through struggle, and it is only through self-emancipation and solidarity that future progress will come. As Frederick Douglass reminds us:

“If there is no struggle there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without plowing up the ground; they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters. This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate