Over the last year the pandemic has ripped through prisons like Joyceville Institution in Kingston, Maplehurst Correctional Complex in Milton and the Toronto South Detention Centre. As public health officials urged us to stay home, practice social distancing and wear masks, prisoners have been left to die.

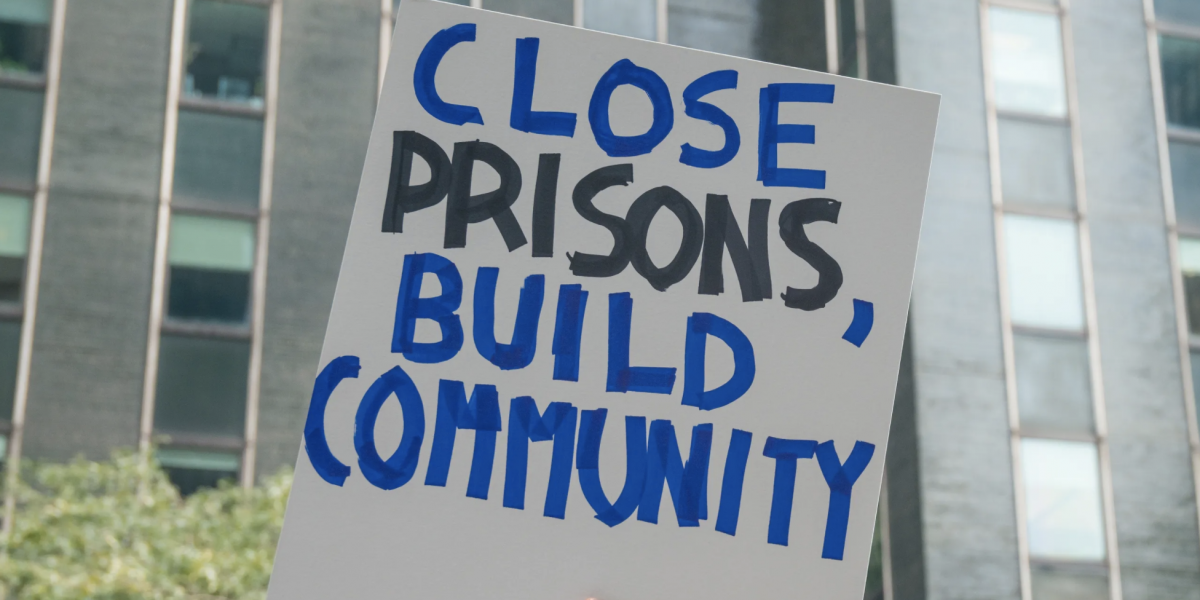

Abolitionist organizations like the Toronto Prisoners Rights Project and the Criminalization and Punishment Education Project have called for the immediate release of incarcerated people from prisons to curb the spread of the virus. But the prison administration’s answer was to keep incarcerated people locked up in their tiny cells. While we sought shelter from the virus in our homes, prisoners were rendered immobile in a storehouse for the virus. Friends and family members told me that they were denied access to the most basic hygienic supplies while guards neglected to wear masks.

Prisons or paid sick days?

The structural inequities that organize our society’s very foundation inside the prison walls are reflected like a mirror in racialized, working-class neighbourhoods. In Toronto, the communities most devastated by the virus are ones like Jane-Finch, Rexdale, and Malvern—home to Black and Brown people and the site of racialized policing for decades. These very same people are denied paid sick days and rent relief while forced to work on the frontlines, hailed as national heroes but left to die in the trenches of the pandemic.

Our communities have been disproportionately impacted by the virus throughout the pandemic. Toronto’s Chief Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Eileen de Villa, revealed that racialized communities constituted 80% of COVID-19 cases in November, and 54% of people hospitalized coming from low-income households. These rates are directly connected to the province’s unwillingness to legislate paid sick days or provide rent relief. The pandemic has exposed pre-existing structural inequities in our society, who must risk their lives for the rest of us to live.

Meanwhile, the Ontario Government decided to invest $500 million over the next five years into expanding Ontario prisons. This new investment does not include the millions of dollars already earmarked for expansion projects across the province, including the highly contentious prison slated to be built in Kemptville.

A different world is possible

As we see a new round of COVID-19 outbreaks inside prisons, we need ensure that our response to this pandemic inside does not continue to harm prisoners’ mental health and well-being. Prison officials must end their reliance on lockdowns and segregation as a means to control the spread of the virus and cope with ‘staff shortages.’

At the same time, we need to improve the conditions of people caged inside prisons by immediately administering COVID-19 tests for all prisoners and staff, providing prisoners with equipment like masks and sanitizer, cleaning supplies at no cost and the daily cleaning and disinfecting of ranges, and ensuring that incarcerated people have access to vaccination as a priority community. People inside prisons are a vulnerable population in a congregate setting. Contrary to the hateful rhetoric espoused by Premier Ford and Conservative Leader Erin O’Toole, incarcerated people need access to the vaccine as a priority community to stop the spread of the virus. Anything less will cause preventable deaths.

But, let there be no mistake: Prisons cannot be reformed, and systemic racism is born into the Canadian Legal State’s very genetic makeup. The incarceration of Indigenous and Black people in Canada is a continuation of settler-colonialism and anti-black racism rooted in the very fabric of Canada’s nation-building project. For instance, behind the prison walls, 30.4% of prisoners are Indigenous, accounting for 4.8 percent of the national population. Black people comprise 8.7 percent of the federal prison population while making up just 3.5 percent of the population. Prisons have little to do with rehabilitation or community safety. These institutions’ primary purpose is to continue to harm Black and Indigenous communities and all other people that the state deems as disposable.

Nothing less than abolition will change this reality.

Imagine the possibilities of defunding, dismantling and abolishing the carceral state? Imagine our resources invested back into life-affirming policies like free public transit, supportive housing, and free post-secondary education. Abolition demands a fundamental shift in how we organize and govern our communities. Defunding police and prisons means investing our resources into building communities instead of destroying them and tearing apart families.

Choosing real safety

In Choosing Real Safety: A Historic Declaration to Divest from Policing and Build Safer Communities for All, a national statement penned by abolition groups and civil society groups from coast-to-coast, we write:

“We wish to stand on the right side of history. We believe we can build a society that values human and other-than-human life and the land, and we commit to shifting away from using badges, guns and cages to manage inequality. Since early winter, rising COVID-19 rates have again made people held in congregate settings like homeless shelters, psychiatric centres and prisons more acutely vulnerable to outbreaks.”

The declaration continues, “We must release as many people that are confined in these settings as possible and start building communities capable of meeting everyone’s needs now. This is crucial from an anti-colonial perspective, a Black liberation perspective, a racial justice perspective, and a public health perspective.”

Indeed, our public funding of policing, jails, prisons and immigration detention vastly exceeds the funds allocated to public housing income assistance, childcare and mental health support. We are organizing to put pressure on the state to reduce police use and prisons with the explicit vision of ending punitive injustice within a generation. How so? Invest into communities–those most devastated by capitalism and racism–by redirecting resources into affordable housing and childcare, healthy food and clean water, public transit and post-secondary education.

One of the authors of the statement, Robyn Maynard, added “it’s time for all facets of society, including labour, harm reduction, the health and education sectors, to commit to ending the anti-Black racism so endemic in this society.” The author of Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to Present continued, “To do so we need to collectively commit to building a future without policing, surveillance, and captivity. In a time of historic Black-led multiracial protests, nearly ten months of hunger strikes led by prisoners, mass evictions and a global pandemic, it has never been more urgent to commit to building safety differently.”

This statement comes at a historic moment. Abolitionist movements have called on us to envision something better for ourselves and our communities. We have shut the door on the status quo through these movements, and there is no going back. Be on the right side of history. Add your voice and sign the historic declaration.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate