“We know our boss will use this virus to enforce rules he wanted already. He’s using the pandemic as an excuse to get control over us. He shouldn’t be allowed to treat grown men this way,” – Joseph, Jamaican seasonal worker.

There’s an active public health crisis on Ontario’s farms, with hundreds of COVID-19 infections and two deaths. A new report by the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change (MWAC) has highlighted how the anti-migrant racism that existed prior to COVID-19 has made the pandemic worse. The report, Unheeded Warnings: COVID-19 and Migrant Workers in Canada, is dedicated to Bonifacio Eugenio Romera and Rogelio Muñoz Santos, two Mexican migrant farm workers who died of COVID-19. It is an urgent call for action to prevent more deaths and to win migrant justice.

Based on the experience of over a thousand migrant workers, the report makes clear that every aspect of pandemic response has been warped by conditions of racism and exploitation—from border closures, to quarantine, to public health advice and corporate bailouts. The dominant COVID-19 response has made life worse for migrant workers, which has in turn worsened the pandemic. But centering migrant justice can help stop COVID-19 and win health and justice for all.

Border closures reduce solidarity, not disease transmission

A global pandemic requires global solidarity. But one of the first pandemic responses from governments around the world was to close the borders—against the advice from the World Health Organization. This, predictably, did nothing to stop the pandemic from spreading—with Italy and the US becoming the global epicentres despite their strict travel bans. But it did succeed in whipping up anti-Chinese and anti-migrant racism, scapegoating racialized communities.

The first impact of Canada’s border closure on March 18 was to strand 74 workers scheduled to arrive from Trinidad and Tobago, who were left without any income or support. The ongoing border closures continued to harm migrant workers and their families, as Gilberto, a Mexican farmworker, reported:

“my flight to travel to Canada on March 31 got canceled due to border closure? My 15 year old daughter has falled sick and needs immediate care including blood transfusion, but I don’t have the money to pay for that. I’m desperate and need income support as my daughter’s life is at risk.”

To add insult to injury, the border closures scapegoated migrant workers for the pandemic. The report explains that “workers also reported increased racism from employers, local shops, and some community members who treat them as if they are ‘disease carriers’ – even in some cases where workers arrived before COVID-19 hit. In all, 209 migrant workers reported increased intimidation, surveillance and threats from employers often under the guise of COVID-19 protocols.”

Repressive quarantine makes pandemics worse

Supporting safe self-isolation is critical during pandemics. But as with border closures, repressive quarantines have historically not worked to stop the spread of disease and have instead served to heighten the health risks for those accused of spreading it. As the report notes, “Under the current regime in Ontario, migrant workers are to be monitored to ensure that if they arrive in Canada infected, those infections do not spread into the community. COVID-19 related measures have not been designed to ensure that migrant workers are themselves protected from risk of infection.”

MWAC pressured the federal government to create guidelines to allow migrant workers to safely self-isolate on arrival, with access to income support, food and shelter, and health information to workers in their own languages. But the report details the routine employer violations of these guidelines: there were complaints from 316 workers of being paid less or not at all during quarantine, or having their income clawed back; 539 reported inadequate access to food, 160 said they couldn’t adequately physical distance, and 109 reported cramped or unclean housing.

Social distancing: the limits of behavioural advice

The main public health response to the pandemic has been behavioural advice, with the mantra of social distancing. But this abstract call is undermined by dangerous working and living conditions. As the report explains, the exploitative conditions for migrant workers directly violate basic public health principles:

“In one incident report, 50 workers from different states in Mexico were placed on one bus from the airport to the local farm for a number of hours. In another instance, nine workers, also from different states, were cramped in one house despite being in quarantine. On another farm, 12 workers were placed in one room with bunk beds. In one incident report, 14 greenhouse workers were placed in one bedroom, sleeping in bunk beds. In many cases, kitchens in particular were areas where workers could not socially distance. In a separate incident, nine workers were made to start work as soon as they arrived at the farm, and were unable to keep distance while working. Greenhouses are some of the worst culprits – we received evidence from eight different greenhouses and 365 workers who were housed in conditions that they were not able to socially distance even during quarantine.”

As with the COVID-19 outbreaks in long-term care homes, the conditions that have created the current outbreak on Ontario farms predated the pandemic by decades. Had governments listened to front-line workers many infections and deaths could have been prevented. As over 100 migrant workers explained in a joint statement two years ago:

“We get sick from the water at our houses as many employers use wells so the water is not suitable for drinking and harms our health. Some of us sleep with up to 10 people to a room with no privacy. Some of us pay up to $360 a month for housing and still share a room with four other people. Also many bunkhouses have no heater or air conditioning or ventilation. Some of the windows in houses are sealed which puts our life in jeopardy as there is no way for us to get out of the house in case of emergency or get some air if it’s too humid inside. We demand a national housing standard system where employers get random inspections, and are not previously informed of inspections as they often hide problems beforehand when they know an inspector is coming. We want to participate without reprisal in these inspections, as our experience and voice has been ignored.”

‘Stay home when sick‘

Similar to the call for social distancing, the behavioural advice to “stay home when sick” is meaningless if you are incarcerated or experiencing homeslessness, or if you are denied paid sick days or forced to live in cramped quarters. Migrant workers experience a combination of all of these—forced to live in unsafe housing controlled by the employer, forced to work in dangerous conditions and denied paid sick days, and threatened with homelessness and deportation if they complain. These conditions threaten health between pandemics, and are magnified during pandemics.

MWAC spoke with migrant workers at Greenhill Produce, where there are at least 100 cases of COVID-19: “Workers confirmed that six workers started with mild symptoms. These symptoms were considered normal, because temperatures inside the greenhouse are very high and with the cold weather outside, workers often get colds. Workers confirmed that they never received any sick days in previous years and this remained the case this year. Only when some workers were sick to the point that they couldn’t get up to go to work, were they tested for COVID-19. Once they tested positive, workers reported being moved into two houses with 20 workers each and just three bathrooms. Each room in the house has six workers in cramped quarter.”

This was not an isolated incident. At Scotlyyn Group, the farm with the largest reported outbreak in Ontario, “We also received a call from workers at this farm who informed us that forty workers were being housed in a single dorm prior to the outbreak with a single shower between them. Multiple workers confirmed that employers instructed workers to keep working in large group settings after testing had begun and before results were announced which many workers believed caused the outbreak to grow.

Government bailouts: for workers or for bosses?

The government has responded to COVID-19 with billions of dollars of bailouts to “support Canadians”. But this has been largely directed at sustaining profits for Canadian corporations, rather that wages for workers—and the nationalist focus on “Canadians” has been used to further exploit migrant workers by denying them access to CERB.

As Winston, a season tree nursery worker explains, “the boss gets money from the government for quarantine costs and still we get a bill for soap and grocery. He’s taking bread from our kids’ mouths—we need to send that money to our families back home!”

From meat processing plants to farming, the government’s response has been to subsidize the very conditions of precarious work that create COVID-19 outbreaks. As the report explains:

“Small and medium sized farmers are being overtaken by large, incorporated farm businesses and the massive multi-million dollar corporations who now control large sectors of the industry… This industrial, highly concentrated model of food production and processing prioritizes economies of scale, output maximization, and speed of production (e.g. drives to increase ‘line speed’) at the direct expense of worker safety, health and well being… Since March 15, 2020, the federal government has given nearly a billion dollars directly to agri-food businesses under the guise of saving family-owned and –operated businesses. But as the Deputy Minister of Agriculture stated, the assistance is not going directly to farmers, but to ‘industry’, who are expected to then support farmers and workers.”

But there has also been important organizing around the bailouts—from tenants organizing rent strikes so CERB doesn’t become a bailout for landlords, to migrant workers organizing to expand access to CERB, and Migrant Students United organizing with the Canadian Federation of Students to expand access to CERB and CESB.

‘We’re all in this together’: Do Black and brown lives matter?

Politicians continue to claim their pandemic response is based on the notion that “we’re all in this together”, a public health version of “all lives matter.” But the worst COVID-19 outbreaks in the country reveal the failures of ignoring the conditions of racial capitalism: denying adequate pay, scheduling and PPE to racialized women Personal Support Workers led to outbreaks in long-term care; enforcing cramped working conditions without paid sick days for Filipino workers led to the outbreak at Cargill; and keeping Caribbean and Latinx workers in dangerous living and working conditions has led to the ongoing outbreak on farms.

“These people are cruel and I’m tired of them,” said Delroy, a season worker for 23 years. “They have no heart for Black people, they use us like slaves.” The pandemic of anti-Black racism fuels the conditions on which COVID-19 thrives, and the racist backlash. Migrant workers reported increased intimidation, surveillance, threats and racism during COVID-19. As the report discovered:

“Critically, while complaints among Spanish-speaking and English-speaking workers are largely consistent, complaints about threats were disproportionately higher for Caribbean workers who are largely Black men (19.7% of Caribbean workers, as compared to 12.8% of Spanish-speaking workers). Racism, and specifically anti-Black racism, underpins workers’ experience.”

Migrant justice now

As the report highlights, “Migrant farm workers have led protests, organized wild cat strikes, marched on their bosses, and spoken to elected decision makers. Throughout this report we have included photos of our members – their faces have been blurred for their safety, but it is their power that guides this work.” The report concludes with 17 calls for change, based on the experience and leadership of migrant workers themselves. These include: permanent status on arrival, health and safety protection, suspending work at COVID-19 farms, ensuring income for all, making quarantine work for workers, creating dignified living conditions, ensuring decent work, and public health not policing.

These would not only help stop COVID-19 but also help ensure health for all, and make the economy resilient to future pandemics. In the context of an active public health crisis these recommendations are urgently needed, and in the context of migrants lives they are long overdue. As Mariana, a single mother of three from Mexico explained, “I want to stay in Canada and continue working, but I don’t have Permanent Resident Status! I have been coming to Canada for 20 years and I believe it is time that we have access to PR.”

- Read the full report here

- Join the June 13 solidarity caravan for migrant workers

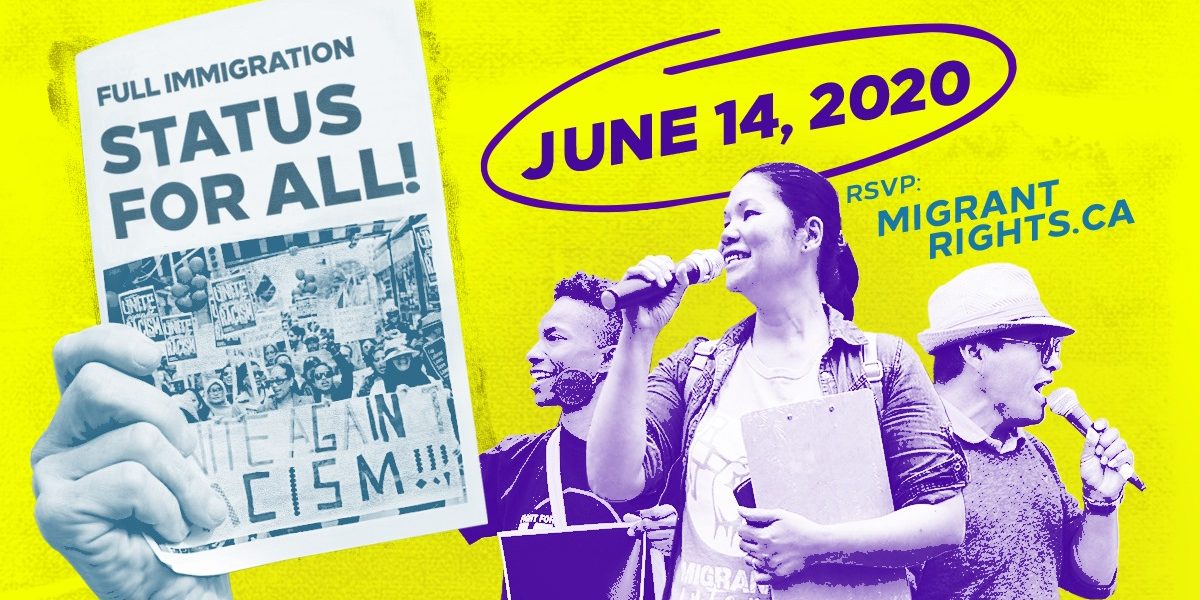

- Join the June 14 mass digital rally for full immigration status for all

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate