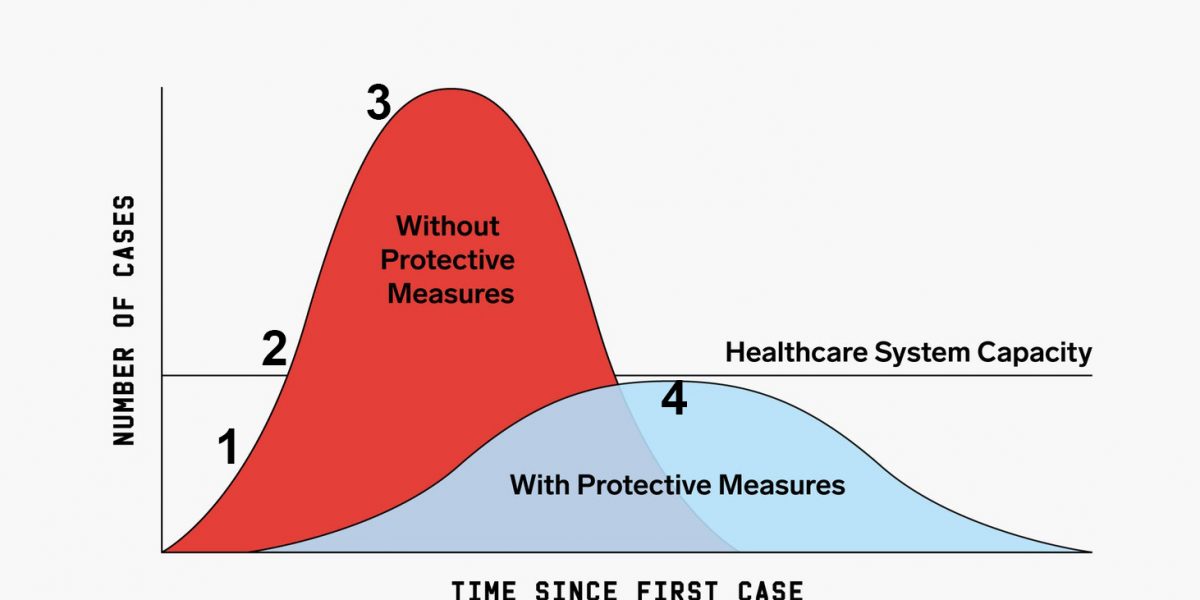

We’re told we need to “flatten the curve” of the pandemic to prevent a health crisis, but how do we do this? We need to consider four basic questions, which address four aspects of the curve: 1) what is the pandemic? 2) why is it causing a health crisis? 3) what won’t work? 4) what do we need?

1. What is the pandemic?

In other words, what is the curve that we need to flatten? If we don’t start by recognizing the nature of the problem we will never be able to address it. We can learn from the history of pandemics that there are actually three inter-related curves. As Jonathan Mann, director of World Health Organization program on AIDS explained in 1987,

“It is useful to consider AIDS as three distinct yet intertwined global epidemics. The first is the epidemic of the HIV infection itself. The second is the epidemic of the disease AIDS…Finally, the third epidemic of social, cultural, economic and political reaction to AIDS is also worldwide and is as central to the global AIDS challenge as the disease itself…AIDS has unveiled the dimly disguised prejudices about race, religion, social class, sex and nationality.”

COVID-19 and AIDS have many differences, but this framework is essentially the same. The first pandemic is the new coronavirus, now called SARS-CoV-2. Thankfully it is not airborne, but it can be easily transmitted by droplets (cough/sneeze), and stays on surfaces. Its incubation is up to two weeks and can be transmitted before any symptoms. This informs basic public health recommendations to individuals: cough/sneeze into your sleeves, wash your hands, clean your surfaces, practice healthy distancing, and self-isolate for 2 weeks if you’re exposed.

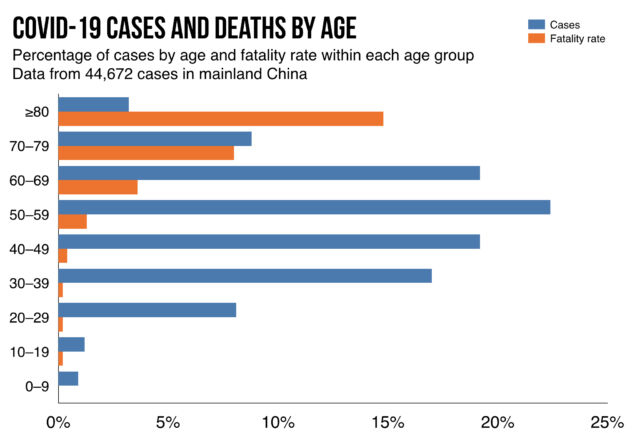

The second pandemic, following the virus’ incubation period, is the disease: COVID-19. It causes fever, cough, difficulty breathing, and potentially pneumonia. Overall 80% of cases are mild, requiring self-isolation and 20% are severe, requiring hospitalization—including 5-10% which are life-threatening, requiring intensive care. But these risks are not evenly distributed: anyone can transmit the virus and get the disease, but the mortality rate rises with age and chronic health problems. The overall mortality rate is 1-2%, which is 10 times that of the flu, but it can be ten times greater for elderly or immunocompromised patients. This reinforces the importance of everyone following public advice, both because anyone can get it, and to protect the most vulnerable.

Then there’s the third pandemic of social, economic and political backlash, especially anti-Asian and anti-migrant racism. To “flatten the curve” we first need to recognize that it includes a pandemic of viral spread, a pandemic of COVID-19, and a pandemic of reaction–all of which need to be addressed.

2. Why is there a health crisis?

In other words, why does COVID-19 overwhelm healthcare system capacity? This is also related to a number of reasons. The first and most obvious is the number of cases and disease severity. If the virus only caused the sniffles then it could infect a billion people, but it wouldn’t cause a health crisis. But because 20% of patients require hospitalization and 10% require intensive care, this contributes to a health crisis.

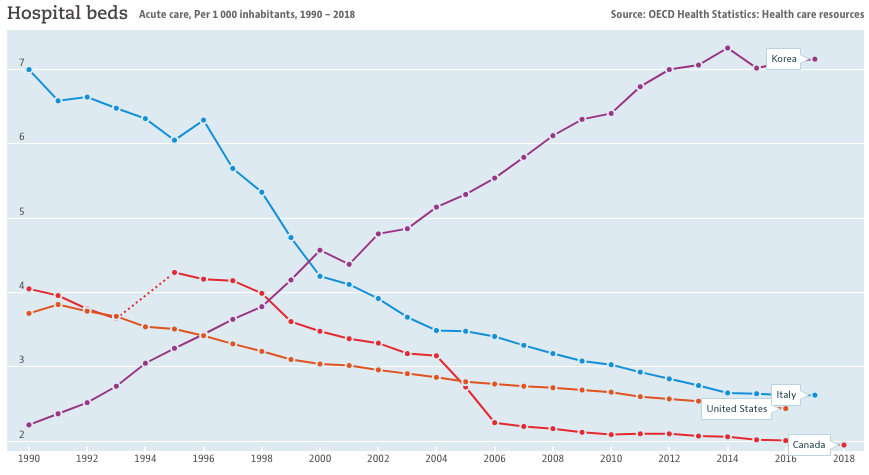

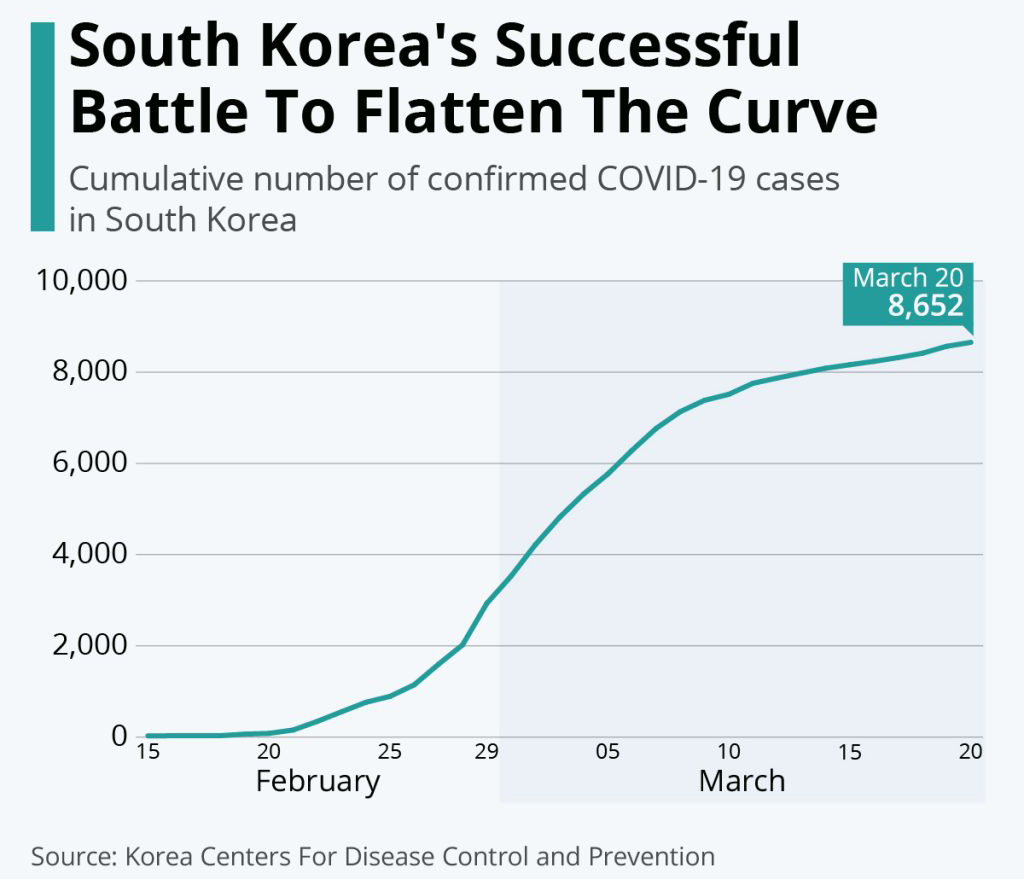

But whether or not a pandemic exceeds healthcare system capacity obviously depends on what that capacity was like before the pandemic, and whether or not it increases during a pandemic. This is the second reason why there’s a health crisis. One of the problems of the COVID curve diagram is it assumes healthcare system capacity is fixed at a level that is not able to deal with surges and which remains fixed even during a pandemic–which is more a reflection of political priorities than biology. If we look at acute care hospital beds per capita in the years before the pandemic we see that Italy, the US and Canada have been cutting for 30yrs, making us less and less prepared for a pandemic, and Canada is the lowest of all of them. On the other hand, South Korea has been expanding hospital capacity for decades.

This directly influences disease severity: the mortality rate of COVID-19 in Italy is 5%, while in South Korea it’s 0.5%. We’re reminded that COVID-19 is serious because its mortality is 10 times that of flu. But COVID-19 in Italy has 10 times the mortality rate of COVID-19 in South Korea, even though it’s the same disease. Part of the reason is because Italy has an older population that are more at risk, but part is also because South Korea has much greater hospital capacity. The lesson is that if Canada doesn’t expand hospital capacity, and expand who has access to this capacity, we could have a mortality rate like that of Italy rather than South Korea—not because of the disease, but because of cuts to healthcare.

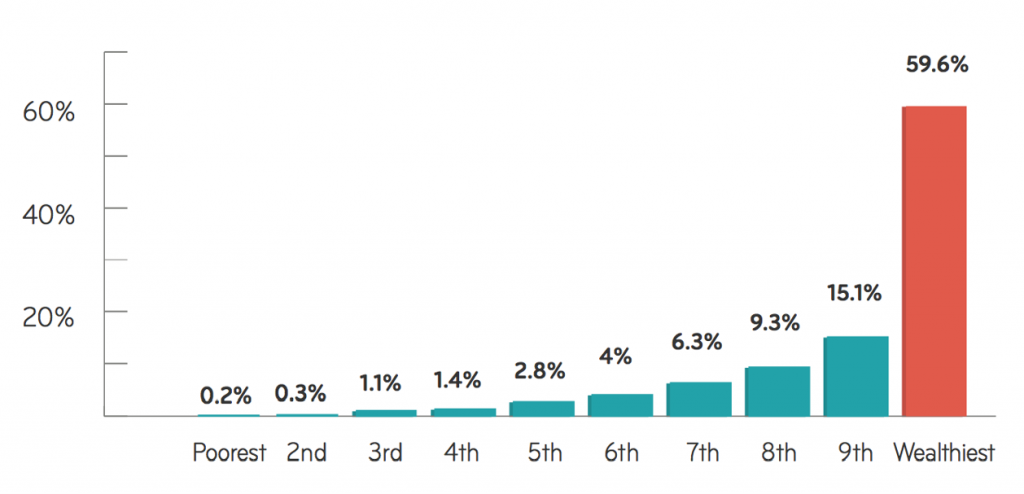

A third reason why COVID-19 is creating a health crisis is inequality. This is directly related for a number of reasons. Poverty and precarious work increases the rate of diabetes, hypertension and coronary artery disease—which are all chronic health conditions that increase COVID-19 mortality and therefore increase the need for hospitalization and intensive care.

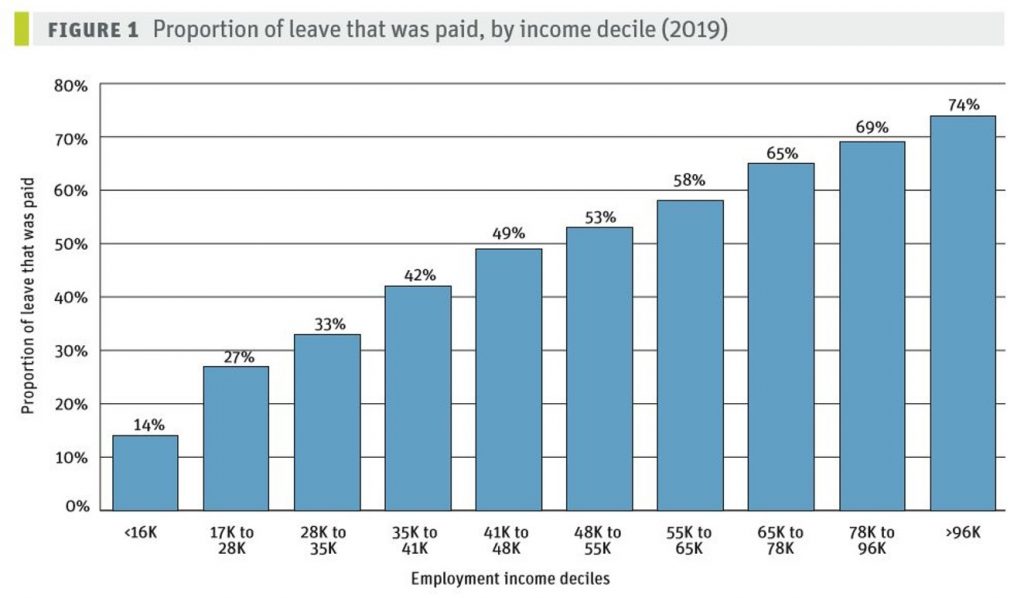

While poverty worsens COVID-19, the layoffs in response to COVID-19 could also worsen poverty, which in turn will worsen health. And inequality denies people access to protective measures. It’s essential that those with mild COVID-19 stay home when sick. But to do this you need a home, which is denied to homeless, evicted and incarcerated people. And you also need the job security and paid leave to be able to stay home. But those with the lowest wages, who are in greatest need of paid leave, have the least access to it. This is not only an economic issue but an equity issue because women, migrants, Indigenous and racialized people are disproportionately concentrated in precarious jobs and denied paid sick leave.

So to flatten the curve below the healthcare system capacity, we need to flatten the curve of inequality that undermines protective measures and expand hospital capacity.

3. What won’t work?

A guiding principle of medicine is to first, do no harm. This is especially important in a pandemic, where we need to guard against policies that not only fail to offer protection, but worsen these intertwined crises.

The first is racism and xenophobia. When it began, the media called it “Wuhan coronavirus” or “Chinese virus”, which led to a racist backlash against the Chinese community and undermined how we understand disease and how to prevent it. As UofT student Frank Ye explained to the media “when we peddle racist ideas, when we peddle xenophobia, that isn’t going to protect you from the virus. Proper public health procedures and precautions will protect you from the virus. Racism won’t.”

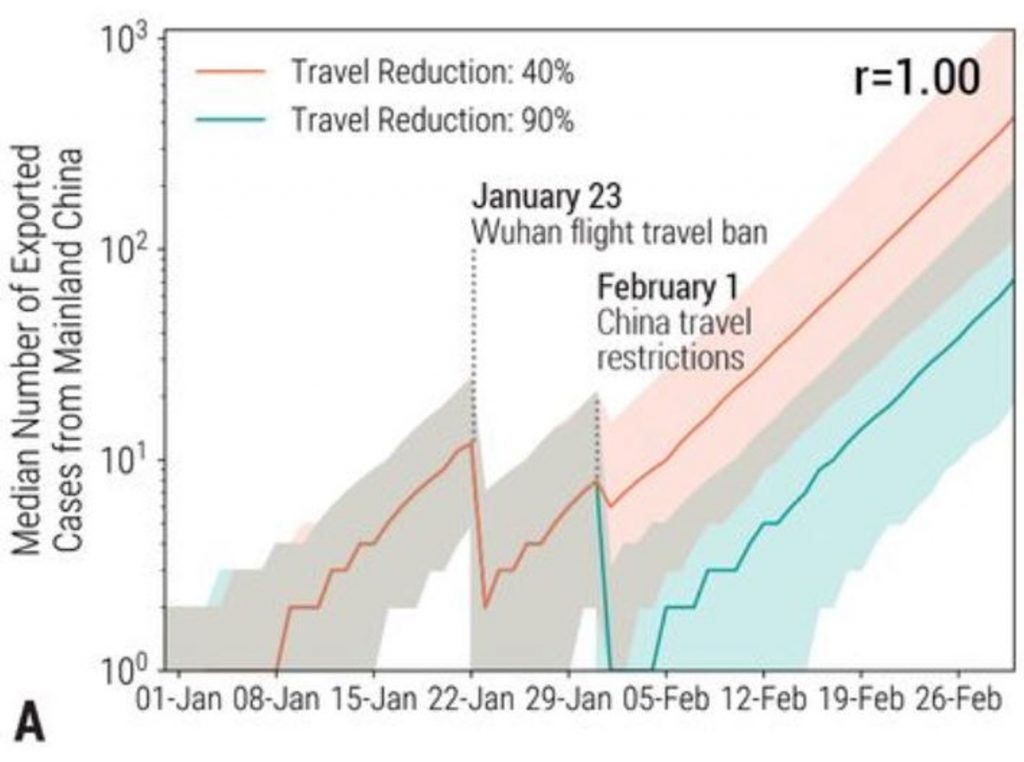

The second response, connected to the first, is travel bans and closing borders. Obviously people should make every effort to limit non-essential travel. But for many people travel and migration are essential for their survival. Travel bans don’t work to stop the first pandemic of viral spread, because of its incubation period and easy transmission. Travel bans didn’t work in China, where Science Magazine found the local travel ban on Wuhan only delayed the epidemic in China by 3-5 days and international travel bans only delayed global spread by 2-3 weeks.

Travel bans also didn’t work in Italy, which was the only country in Europe to ban all flights from China and is now the epicenter of the disease.

Closing borders does nothing to help expand healthcare capacity so we can deal with the second pandemic of COVID-19. Trump makes this clear: he banned travel from China and then Europe and yet can’t be bothered to get enough testing for people in the US, millions of whom are denied healthcare. Closing the borders fans the flames of the third pandemic of xenophobia, making it seem like COVID-19 is a foreign invader and equating it with migrant and racialized people. Trudeau made this clear, with his travel ban which is actually a citizenship ban because it exempts Canadians and Americans from the border closure. The problem is not the exemption, it’s the border control which does nothing to keep us safe, and only medicalizes anti-migrant racism. It’s a victory that the migrant rights movement has partially re-opened borders to international students, farm workers and care workers.

The third strategy that won’t work is forcible quarantine. Quarantine is the act of isolating people who have been exposed to an infection but have not developed symptoms. Because the virus has an incubation period up to two weeks, it’s essential for those who have been exposed to isolate themselves for this period. But to do this on a mass scale we need to empower everyone to isolate themselves, not threaten a minority with forcible quarantine. Throughout history, quarantines have become repressive measures used by states to persecute marginalized communities—from the quarantine of Chinatown in San Francisco in the 1900s, to the quarantine of African migrants in Italy in 2020.

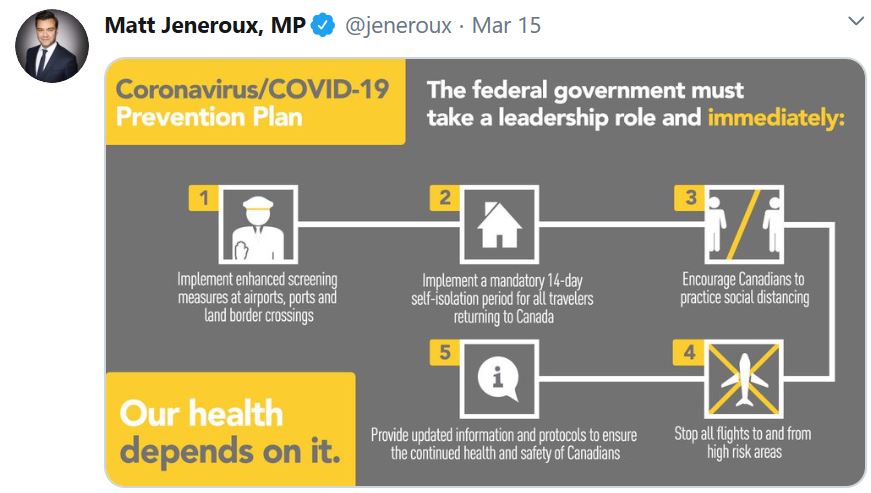

We can see the politics of quarantine from the Conservative health critic:

It starts with border control and leads straight to mandatory quarantine. This implies that Coronavirus is a foreign threat that must be forcibly contained, which spreads the third pandemic of racism/xenophobia. It then says to “encourage Canadians to practice social distancing” without empowering workers in any way to actually practice this. The refusal to provide paid emergency leave will worsen the first pandemic of viral spread. Then it goes back to xenophobia by banning flights from so-called high-risk areas and ends of with vague calls for information and protocols without addressing hospital capacity to deal with second pandemic of COVID-19. So according to the Conservatives, our health depends on border control, travel bans and forcible quarantine, expanding the powers of the police rather than the capacity of hospitals or the financial ability of workers to self-isolate.

4. What do we need?

We obviously need to massively expand protective measures to flatten the curve. But xenophobia, border control and forcible quarantine won’t work. Fortunately there are many policies that will, and that we desperately need—including these three.

First is expanding healthcare, and access to healthcare. South Korea shows that universal healthcare, large hospital capacity, mass testing, and pay for those in isolation can help reduce mortality rates and flatten the curve.

Here in Ontario we have multiple barriers to healthcare, but we’re already starting to address them. Public pressure has pushed Ford to open up hospital beds, open up free testing centres, eliminate the waiting period for OHIP, and cover healthcare costs for uninsured people. We need to expand all these, and make them permanent

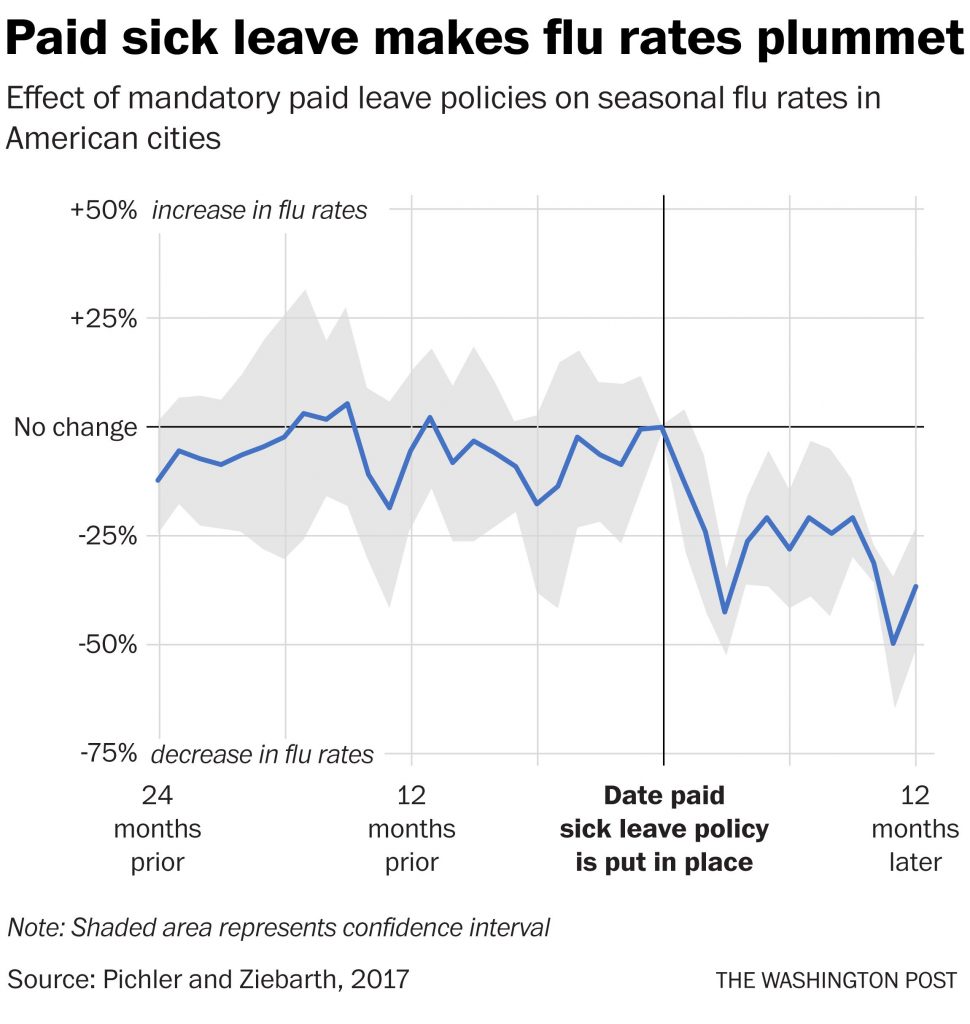

Secondly, we need to expand paid emergency leave for all. We know from influenza that lack of paid sick days leads to greater infections, and that winning paid sick days helps reduce infections.

A number of provinces, from Alberta to Ontario, have won job protected leave but this has to be paid if we want to reduce COVID-19 crisis and associated inequality. As a recent report from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives explained,

“In the five lower-to-middle-income professions where women are most likely to be employed — caring, clerical, catering, cashiering and cleaning — only one type of job (clerical work) could potentially be done from home. The other four are by definition in-person jobs, and workers in three of these professions — caring (in health care, child care and long-term care), catering (food preparation) and cleaning — will be on the frontlines of combatting the virus. The stress on the primary care and long-term care systems will be borne largely by the women who staff these frontlines. Ensuring that sick workers stay home…will be critical in slowing the spread of COVID-19.”

Thirdly, we need to expand employment insurance for all. Otherwise the layoffs associated with COVID-19 will drive more people into poverty, worsening the crisis of inequality, which itself would be a health disaster.

For these reasons the Decent Work and Health Network has been advocating for paid emergency leave, so sick workers can recover at home and protect the public; access to EI, to reduce income inequality which is a key social determinant of health; and for opposition to racism and xenophobia.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate