With the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring the new coronavirus a pandemic, it’s urgent that countries around the world escalate public health efforts. These include both containment (identifying and isolating the initial cases) and mitigation (reducing the spread and impact throughout the community). But how will these be carried out, and in whose interests? While many are siding with state-enforced border control and forcible quarantine, there are much more effective options that are available and long overdue, which would not only lessen the impact of COVID-19 but also make the world a better place. Will we advocate for rights—including Indigenous rights, migrant rights, women’s rights, housing rights, disability rights, healthcare rights, and labour rights—or repression?

Border control: COVID-19 doesn’t respond to xenophobia

In a pandemic it obviously makes sense for people to limit their non-essential travel. But for some, migration is absolutely essential to flee war, persecution and climate disasters. Calling for border control to stop coronavirus both medicalizes anti-migrant policies, and builds illusions that we can stop viruses at the border.

During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, numerous countries imposed travel restrictions, and the WHO summarized the limited results: “Internal travel restrictions and international border restrictions delayed the spread of influenza epidemics by one week and two months, respectively…Travel restrictions reduced the incidence of new cases by less than 3%…Travel restrictions would make an extremely limited contribution to any policy for rapid containment of influenza at source during the first emergence of a pandemic virus.”

Now we’re facing a new coronavirus with a longer incubation period than influenza, so it can spread much further before detection. So it’s not surprising that even severe travel restrictions have had such limited impact both within and between countries. People in China did much to limit the spread of COVID-19—from health providers who identified the virus and treated the first patients, to the expansion of hospitals and public health teams—but the state’s militarized lockdown of Wuhan and other countries’ travel bans accomplished little. As Science magazine summarized:

“At the start of the travel ban from Wuhan on 23 January 2020, most Chinese cities had already received many infected travelers. The travel quarantine of Wuhan delayed the overall epidemic progression by only 3 to 5 days in Mainland China…While the Wuhan travel ban was initially effective at reducing international case importations, the number of cases observed outside Mainland China will resume its growth after 2-3 weeks from cases that originated elsewhere.”

The xenophobic hysteria about a “Chinese virus”, which justified travel bans, were ineffective at stopping the pandemic but were very effective at spreading anti-Chinese racism. Plus these restrictions are illegal under the International Health Regulations (IHR). As an article in The Lancet explained:

“Under no circumstances should public health or foreign policy decisions be based on the racism and xenophobia that are now being directed at Chinese people and those of Asian descent. Many of the travel restrictions implemented by dozens of countries during the COVID-19 outbreak are therefore violations of the IHR…Some countries argue that they would rather be safe than sorry. But evidence belies the claim that illegal travel restrictions make countries safer. In the short term, travel restrictions prevent supplies from getting into affected areas, slow down the international public health response, stigmatise entire populations, and disproportionately harm the most vulnerable among us.”

The most unfortunate confirmation of the failure of travel bans is Italy, which is in the midst of a healthcare crisis with more than 15,000 cases and more than a thousand deaths. As the chair of the European Parliament’s public health committee acknowledged: “The only country in Europe that has banned direct flights from China when the Coronavirus started was Italy. Italy is today the country which is most hit by Coronavirus. So the least I can say is that stopping flights was not an effective response for Italy to stop importing the virus.”

With all the focus on China, an early case in northern Italy with travel from Germany was not detected until too late, which emphasizes the importance of public health screening. But instead local media created a story that blamed a Pakistani migrant worker delivering Chinese food.

Forcible quarantine: scapegoating undermines public health

Obviously those exposed to infection and those with confirmed infections should limit their contact with others, but how is this done? Technically, “quarantine” refers to the isolation of healthy people who have been exposed to and remain at risk of developing an infection but are not yet showing symptoms, as opposed to “case isolation” which is directed at those with symptomatic and confirmed infections.

The Public Health Agency of Canada distinguishes between “voluntary home quarantine (self-isolation)” or “mandatory quarantine” for those exposed to infection, and “isolation” for confirmed cases. The key question is whether this is voluntary of coerced, and from its inception in the 14th century to its resurgence in the late 20th century, the term quarantine has often been used to refer to coercive measures applied by the state, whether or not people have symptoms or confirmed infections. Historically, quarantine is not something people do, it’s something that’s done to them, and there is a long history of its effectiveness not in fighting disease but in scapegoating racialized communities. As Richard Schabas, Ontario’s former chief medical officer explains:

“When I trained in public health, some 25 years ago, quarantine had fallen into disrepute because of the wide-spread perception that it did not work. The term quarantine came back into prominence in the mid-1980s to describe an (inappropriate) strategy for controlling the spread of HIV (really case isolation, not quarantine). In recent years, quarantine has become respectable again. This began in the context of post-9/11 concerns about bioterrorism, although it has never been clear against which bioterror threats quarantine would be useful. Mass quarantine gained further currency when it was adopted as a control strategy against severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003.”

When HIV emerged, it was blamed on the LGBTQ community, Haitians, drug users, sex workers and hemophiliacs–all of whom were labeled as inherent “risk groups” who threatened everyone else. Using the language of quarantine, there were calls to shut down bathhouses and quarantine gay villages, incarcerate drug users and sex workers, detain Haitian refugees and ban children with hemophilia from schools. These repressive measures made the epidemic worse, and it was only by fighting them—asserting LGBTQ rights, sex worker rights, migrant rights, drug user rights, hemophiliac rights, and healthcare rights—that people developed the real tools to address HIV including sex education and safe sex, clean needles and a clean blood supply, and access to medicine.

With SARS, quarantine measures (in terms of the isolation of healthy contacts of SARS cases) consumed many resources, with little impact beyond heightening the sense of panic—which fanned the flames of anti-Chinese racism. As Schabas explained, “SARS quarantine was ineffective because compliance was poor — no higher than 57% and possibly much lower. The costs, in terms of wasted resources and public anxiety and intolerance, were substantial. Travel advisories for SARS, a form of modified quarantine, were also unnecessary. SARS was, in fact, rapidly eradicated by effective isolation of cases in hospitals.”

With COVID-19 one of the first international quarantines was placed on the Diamond Princess cruise ship after 10 passengers developed the infection. But this so-called containment strategy instead became an incubator of coronavirus. After two weeks of forcibly containing overworked staff and elderly passengers in cramped quarters, nearly 700 had infections and seven died. Meanwhile, Canada has begun using military quarantine for COVID-19, which didn’t lead to additional cases but did prove unnecessary. Of the more than 600 people kept for two weeks at Canadian Forces Base Trenton after evacuation from Wuhan and a cruise ship off California, only one has COVID-19—which could have been detected through public health screening like every other case in Canada. But after Trudeau normalized military quarantine, the Conservatives are pushing for greater state-imposed restrictions.

Those calling for quarantine (rather than voluntary self-isolation) should realize where this leads: Conservative Health critic Matt Jeneroux called for “mandatory quarantine and stopping incoming flights from those areas” and asked, “The government has the ability under the Quarantine Act to require all individuals who have visited high-risk areas to be placed in quarantine. When will they use it?” By appealing to the Quarantine Act, the party of “small government” is invoking state repression—including up to a million-dollar fine and three years in jail—and directing it at “those high-risk areas” by which they means China and Iran, but unlikely the US (despite it being much closer, with more travel and and unknown number of cases due to lack of testing).

This is not a hypothetic concern. In Italy, quarantines were used before COVID-19, and have now been rationalized on medical grounds. Last year interior minister Matteo Salvini oversaw the quarantine of 131 African migrants, rescued in the Mediterranean, in insanitary conditions that the coast guard commander called “unnecessary cruelty.” Now Salvini, leader of the far right Northern League, is medicalizing his anti-migrant racism by equating racialized communities with viral infections (a classic fascist tactic): even after the Italian government quarantined 276 African migrants for two weeks to check for coronavirus (and finding none), Salvini declared that “The government has underestimated the coronavirus. Allowing the migrants to land from Africa, where the presence of the virus was confirmed, is irresponsible.”

Mitigation: social distancing, social change

With containment strategies failing there’s a shift to mitigation, from tracking and treating infections to reducing transmission. But those pushing for the most repressive containment measures are also least interested in basic mitigation. Trump imposed a travel ban on China but can’t seem to be bothered to make widespread testing available across the US. The British Tories have empowered the police to enforce quarantine, but refuse to restore their cuts to healthcare–and have even suggested that people simply develop herd immunity, a process that would require the infection of 40 million people.

The Canadian Conservatives are calling for expanding quarantine instead of expanding public healthcare. Canadian hospitals are already over-capacity before COVID-19 (thanks to decades of Conservative and Liberal cuts at the federal and provincial levels), and if both levels of government don’t rapidly expand capacity we could very quickly run out of hospital beds like the tragedy unfolding in Italy. Meanwhile, despite the claims of anti-vaxxers about BigPharma profiting from vaccines, the major pharmaceutical companies are not interested in preventing unpredictable infections. So to mitigate COVID-19 we need to strengthen healthcare rights–including expanding public healthcare, and providing free access to vaccines and anti-virals if they become available.

Meanwhile there are calls for “social distancing” under the banner “cancel everything”. Like non-essential travel, restricting voluntary exposures to large numbers of people obviously makes sense. But any social policy will fail without addressing the factors that prevent people from staying at home or the impacts of canceling public services. Of course people should stay home when they’re sick to avoid close contact with others. But this is impossible for those experiencing homelessness, who have no choice but to sleep in public places or overcrowded homeless shelters. As street nurse Cathy Crowe explained, “Shelters are like a petri dish waiting for COVID-19 to arrive”, with all the problems of The Diamond Princess “except shelters are more crowded, have even worse ventilation, poorer staffing levels and cleaning standards.” So to mitigate COVID-19 we need to strengthen housing rights, like the petition to ban evictions during the pandemic.

This is especially true of communities who are disproportionately impacted by inadequate housing. A month ago the media was railing against Indigenous blockades that called for shutting down Canada, but now the media is calling for cancelling everything—without addressing the colonial conditions that sparked the blockade and that continue to shape the government’s disaster response. During the H1N1 pandemic the only help the federal government sent reserves in Manitoba was body bags; more than a decade later there’s still a lack of housing and clean water, which undermines response to COVID-19, but the government is only offering tents. So to mitigate COVID-19 we need to strengthen Indigenous rights.

Viruses don’t discriminate but their impacts do, because of pre-existing social and economic inequalities. American disability organizations sent a letter to the government outlining key COVID-19 mitigation strategies for people with disabilities: “1) continuity of services for persons with disabilities who require them for their health and daily functioning; 2) access to actionable information for persons who require accessible forms of communication, including persons with vision or hearing disabilities; intellectual and developmental, autism, cognitive, learning, reading and information processing disabilities; 3) ensuring the daily needs of persons with disabilities are met for food, housing, healthcare, and community support, which are provided by personal caregivers or community agencies; 4) how to operationalize the living arrangements throughout quarantines that potentially may be particularly burdensome for persons with disabilities and their families; 5) ensuring equal access to necessary diagnostic tests and protective equipment; and 6) the provision of training for agencies and their employees in their legal obligations with regard to persons with disabilities.” So to mitigate COVID-19 we need to strengthen disability rights.

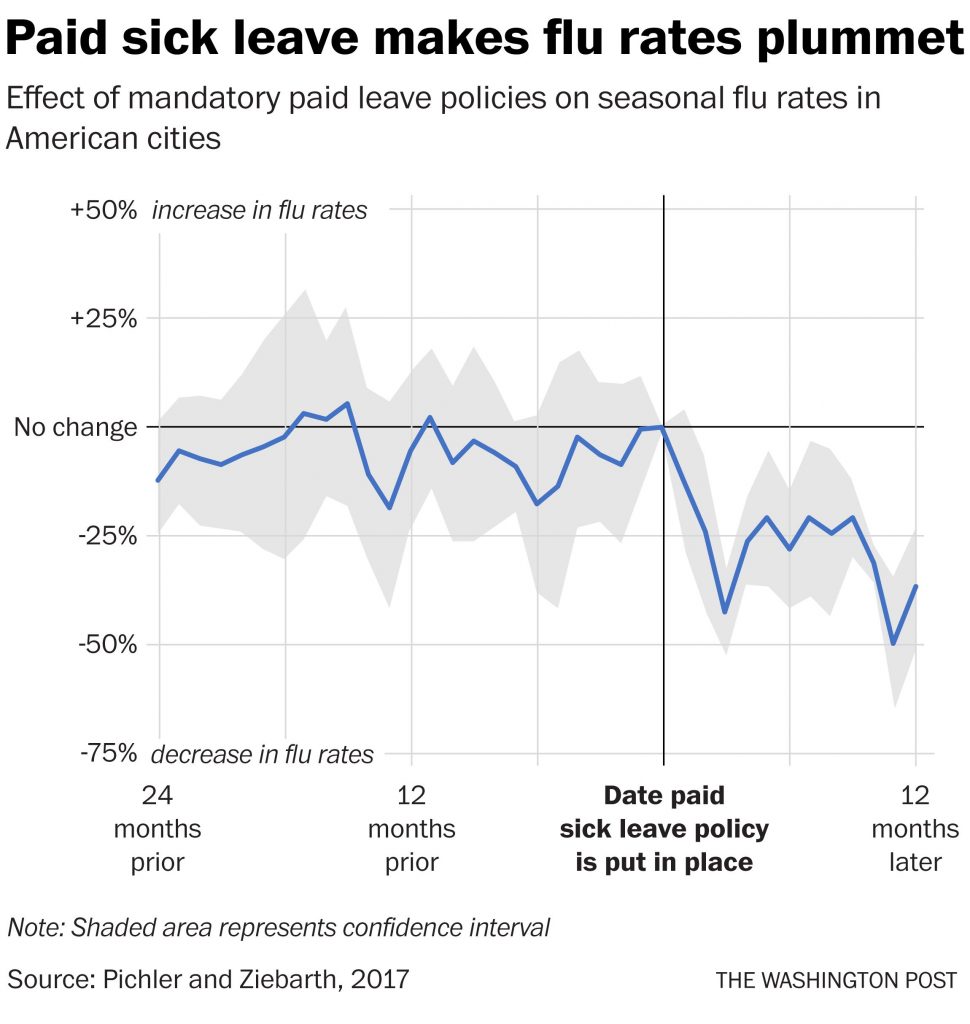

Staying home from work is also an unrealistic demand for those who would lose wages or their job without paid sick days. On the other hand, there’s clear evidence that paid sick days improve immunization rates, reduce ER visits, and make it easier for workers to stay home when they are sick and to keep their sick kids at home. Paid sick days fight the flu:

So to mitigate COVID-19 we need to strengthen workers rights. There have already been important victories: the decent work movement in the US just pushed Trump to agree to 14 paid sick days and three months paid emergency leave throughout the pandemic. Even Alberta’s Jason Kenney has announced to 14 paid sick days and an end to doctors notes for COVID-19, and we need to win theses as permanent measures across the country.

This is especially the case for women—who are the majority of paid and unpaid health workers and caregivers, who are disproportionately denied paid sick days, union protection and employment insurance, and who will be disproportionately shouldered with caring for sick family members or children when schools are closed. As a Johns Hopkins epidemiologist explained, “When you close schools and have kids stay home, the kids who participate in free and reduced-price meal programs might not have access to food. Or their parents who now have to stay home with them might be hourly-wage workers, and so they’re missing out on their paycheck. Maybe those parents are health-care workers and so now maybe the local hospital is down personnel.” So to mitigate COVID-19 we need to strengthen women’s rights—including pay equity, paid sick days and childcare.

Of course we need to follow basic handwashing and sneezing etiquette. But a real mitigation strategy can’t just focus on individual behaviour and the illusion of self-isolation, and it can’t succumb to state repression that dresses itself up as public health. Even as we engage in “social distancing” we need a collective strategy aimed at conditions that put us at risk of COVID-19. As health writer Andre Picard wrote:

“We have to pro-actively seek out cases with greatly expanded testing, up to and including at-home and drive-thru testing (a South Korean innovation), to keep people from going to the emergency room. We also need thoughtful policies to support Canadians harmed by social distancing, from streamlined employment insurance to support for parents, including emergency daycare for people working in essential services.”

Pandemic respiratory infections come and go, and the current explosion of COVID-19 will eventually fall. But what sort of demands we make, and what sort of movements we build now will not only affect the scale and impact of COVID-19, but the kind of world we are left with. Will we call for even more militarized borders, even more xenophobia and racism, even more state repression–all of which will worsen the impacts of COVID-19. Or will we collectively strengthen Indigenous rights, migrant rights, housing rights, women’s rights, disability rights, healthcare rights, and workers’ rights– all of which will not only help “flatten the curve” of COVID-19 but also flatten the deadly inequalities that have plagued us for so long.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate