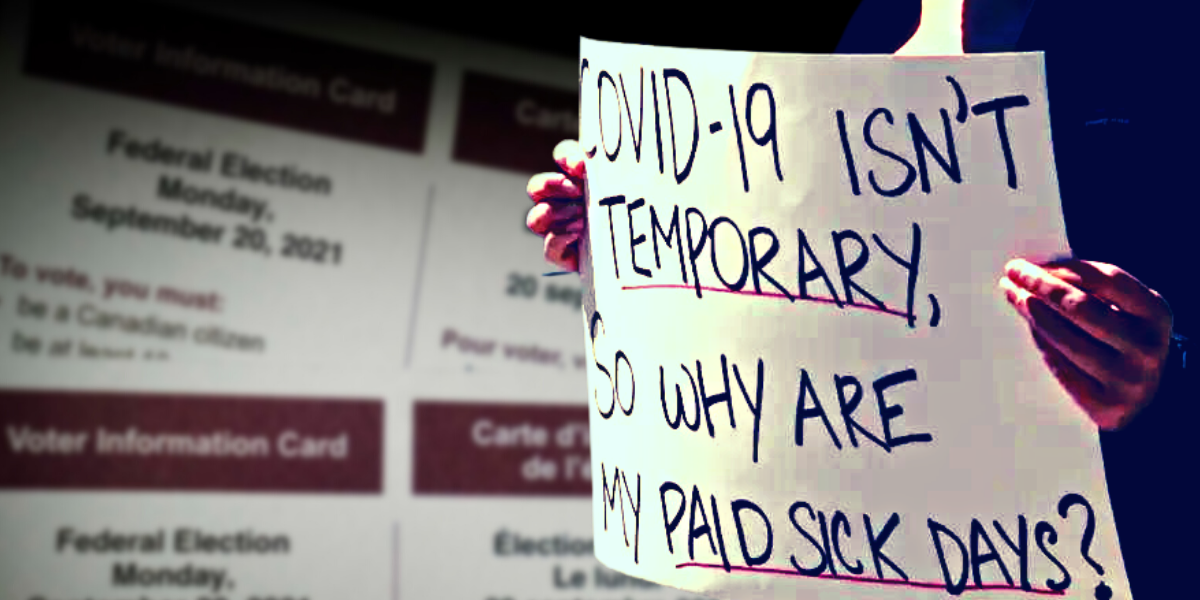

As we head into a federal election in the midst of a rising fourth wave of COVID-19, both the Liberals and the NDP have promised they would legislate 10 permanent paid sick days for federally-regulated workers and work with the provinces to encourage paid sick days for provincially-regulated workers. These promises reflect years of movement organizing, before and during the pandemic. The election provides an opportunity to amplify the movement for paid sick days across the country and build momentum after the election.

Pre-election

Across the country 58% of workers don’t have access to paid sick days, and this rises to three quarters of low-wage workers—who are disproportionately migrant and racialized. For years the decent work movement has been demanding paid sick days as an issue of worker rights, public health, and equity. In 2018 the movement won three paid sick days for federally-regulated workers (in industries that cross provincial borders—like aviation, transportation and telecommunication), and two days for workers across Ontario and Quebec. But the next year the Ontario Conservative government cut these two days, a year before the pandemic.

COVID-19 exploited gaps in paid sick days, and fuelled outbreaks from farms to factories and long-term care homes. The main public health message during the pandemic has been “stay home when sick”, but this is an impossible demand for low-income workers struggling to pay for food and rent if staying home means losing wages. This disproportionately affects migrant and racialized workers who are concentrated in low-wage and precarious jobs. The pandemic has exposed the absurd reality that front-line essential workers most exposed to the virus have the least access to paid sick days.

But as obvious as the demand for paid sick days has become, this was not an automatic response to the pandemic. The dominant response to the first wave was not to expand labour rights but instead to stoke anti-Chinese racism and close borders. This did nothing to stop COVID-19, and it took months of organizing and mobilizing by the migrant justice and decent work movements to shine a light on the conditions of precarious work that were actually fueling the pandemic.

This organizing has now impacted party platforms at both provincial and federal levels. Just a few years ago the Ontario Liberals and NDP only supported 2 and 5 paid sick days respectively, but this year both parties tabled legislation for 7-10 permanent and employer-paid sick days—and the NDP in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia support 10 permanent paid sick days as well. These demands have now spilled over into federal party platforms. Just two years ago the Liberal platform made no mention of expanding paid sick days to federally-regulated workers, and did not expand these days during three waves of COVID-19. Instead the Liberals provided retroactive income supports (the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit, or CRSB) and left the question of paid sick days up to the provinces. The sudden promise of legislating 10 paid sick days for federal workers, and convening the provinces to expand paid sick days, clearly reflects the impacts of the movement.

Similarly, the federal NDP claimed last year that they had secured “paid sick days for all workers in Canada”, by which they meant the CRSB. But paid sick days need to be universal, permanent, adequate, fully-paid, and immediately accessible through employment standards. The federal CRSB provides retroactive economic support for those who qualify, but it fails every criteria for paid sick days—which are provincial jurisdiction for the large majority of workers. The claim that the temporary and federally-funded CRSB was the same as permanent and provincially-legislated employer-paid sick days not only gave cover to the BC NDP to avoid legislating paid sick days, but also allowed the Ontario Conservatives to use the same logic.

For months during the last two waves of COVID-19, provincial governments across the country insisted they didn’t need to legislate their own paid sick days because paid sick days already existed at the federal level in the form of the CRSB. The Conservatives went further, claiming the dangerous gaps in public health were not in workplace protections but border control. As Ford claimed in December, “there’s just not enough to protect us from the threats coming in from outside, at our borders, on a daily basis. Without further action by the federal government at our borders, we remain at extreme risk right now.” At the time travel accounted for only 0.31% of COVID-19 cases in Ontario, while workplaces have accounted for a majority of outbreaks.

It was only after the third wave that the decent work movement was finally able to push a number of provincial governments—the BC NDP, Conservatives in Manitoba and Ontario, and Liberals in Nova Scotia—to partially legislate paid sick days. The movement pushed Doug Ford—through petitions, demonstrations, phone zaps, outcry from health providers, and city council motions—from opposing paid sick days to promising “the best paid sick days in North America.”

These provincial reforms finally provided accessible paid sick days through employment standards, which has been important for encouraging vaccination and staying home when sick. But these partial victories are not complete. By excluding gig workers, the Ontario Worker Income Protection Benefit (WIPB) is not universal; by capping at $200/day it is not fully paid; by only providing three days it is not adequate; and as a temporary program it is not permanent. The WIPB was supposed to expire in just a few weeks, in the middle of the fourth wave, but the government was forced to extend it until the end of the year. But the pandemic is not expiring at the end of the year, extending the program doesn’t help those who have already used their three days, and never helped gig workers who are misclassified. All workers need 10 permanent and employer-paid sick days, and this needs to be part of demands to end misclassification for gig workers, and provide status for all.

Election

This is the context for the federal election: a pandemic fuelled by precarious work, which governments have tried to ignore, deflect responsibility or search for scapegoats instead, but which movements have won partial gains. The federal election is an important opportunity to support the expansion of 10 permanent paid sick days for federally-regulated workers, build pressure on provincial governments to follow, and insist that paid sick days be universally available to all workers and fully-paid by employers.

Conservative leader Erin O’Toole has been portraying himself as a friend of workers, including in the gig economy. But nowhere in the Conservative platform is there any mention of paid sick days, and their actual proposal for gig workers echoes Uber’s misclassification campaign. If O’Toole cared about workers he would support migrant workers, but instead he has been stoking xenophobia: “As soon as COVID-19 began to spread, Conservatives called on the Liberals to take action to secure the border and prevent the spread of the virus in Canada. Justin Trudeau has done next to nothing to keep dangerous variants from Brazil, South Africa and the United Kingdom out of Canada.”

The call for universal paid sick days will be important to shine a light on the real factors that fuel the pandemic, and the need for migrant justice and workers rights. This can also put pressure on the Green Party, whose platform also does not include paid sick days.

The call for paid sick days can also expose Trudeau’s record on migrant workers. Migrant workers are denied status—which undermines access to everything from minimum wage to paid sick days, and from securing housing to refusing unsafe work. If Trudeau supports expanding paid sick days he should provide status for all, a reform at the federal level which would make it possible in practice for migrant workers (whether federally or provincially regulated) to access paid sick days. The call for status for all during the election will also be essential to push back against the xenophobia of the Conservatives, expose the record of the Liberals, and push all parties to support migrant justice.

The federal NDP call for 10 paid sick days echoes their provincial counterparts in Ontario, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia. Pushing the NDP to continue amplifying this call during the election can encourage provincial parties to keep pushing legislation. This is especially important in BC, where the NDP have provided three government-subsidized paid sick days until the end of the year, and promised permanent paid sick days after that—though how many and who pays is not specified. They have launched a bizarre petition to support permanent paid sick days. But they don’t need to: they are the government and don’t need to petition themselves. They have a majority, and could could legislate 10 permanent and employer-paid sick days at any time.

Raising the demand for paid sick days will help build pressure on both federal and provincial governments and across every party, both during and after the election.

Post-election

If the Conservatives win, the decent work movement will be crucial to oppose racism and build working-class unity. While Trump won in 2016, many states also voted to increase the minimum wage, and the fight for paid sick days continued throughout his presidency and outlasted him. There are now more states that provide paid sick days after Trump’s presidency than before, showing that what matters most is not who’s in office but who’s in the streets.

If the Liberals win, it will still take the movement to keep them to their promises. Last election they promised a federal $15 minimum wage, but it took another year of pressure to hold them accountable. If the BC NDP have to petition themselves to deliver paid sick days, then pressure would also need to be placed on the federal NDP should they win.

The movement has now pushed both Liberals and NDP to support paid sick days at both federal and provincial levels, and needs to insist that these be employer paid. The federal Liberals have promised to “immediately convene the provinces and territories to discuss legislating sick leave across the country,” but “these discussions will be informed by consultations with small businesses from across sectors.” But why? There is no evidence that paid sick days ruin small businesses. Wherever employer paid sick days have been mandated, they have been resisted by big business but had no significant impact on small business. When New York City mandated paid sick days years ago, the President of the Manhattan Chamber of Commerce claimed that, “Putting the entire cost of paid sick leave solely on the backs of the small-business community adds additional financial burdens to their already over-taxed and over-fined small businesses.” But a survey of employers—the majority of whom were small businesses—found broad support for paid sick days a year after legislation, because they improve worker health and reduce workplace infections.

The claim that paid sick days harm small business is a long-standing big business tactic, which is used to oppose the expansion of paid sick days or to relieve employers of the responsibility of paying for them. Employers like Amazon, Loblaws and Extendicare have made billions during the pandemic, received government subsidies, and yet still denied paid sick days. To provide further government funds to cover paid sick days means subsidizing employers who deny paid sick days and who have fueled the pandemic.

Trudeau’s promise of business consultations echoes the BC NDP, who are “seeking input from workers and employers on their current paid sick leave programs and on what they would like to see in a province-wide mode.” But anybody can fill out the employer survey, and the questions are geared towards amplifying the myths about paid sick days inviting abuse or harming the economy, and employers are invited to choose how many paid sick days they would like to provide workers or ask the government to cover the costs. This is like having an online survey about whether or not people support vaccination, and inviting people to choose from a selection of vaccine myths or to say how many times they would like to be vaccinated–rather than presenting the scientific evidence, countering the myths, and forming public policy based on public health.

We don’t need to reinvent the wheel: 42% of workers already have access to permanent and employer-paid sick days, and these are proven to benefit workers, public health and the economy. The remaining 58% of workers—the majority low-wage and racialized—don’t need a second class version of paid sick days, they need access to the same permanent and employer-paid paid sick days.

This election comes at a critical time: in the midst of the fourth wave, and in the lead up to some provinces ending their temporary paid sick day programs. The pandemic has revealed the deadly cost of denying paid sick days and the disproportionate burden this places on low-income and racialized communities. The pandemic has also revealed the lengths governments will go to stoke xenophobia rather than ensuring equity in basic workplace protections. But organizing through the pandemic has also shown that movements can push both federal and provincial governments across all parties to deliver partial reforms and bigger promises. Now the movement can use the election to amplify the demand for permanent and employer-paid sick days for all, and build momentum beyond the election to finally turn the demand into reality.

For more information visit Justice4workers, Decent Work and Health Network, and Migrant Rights Network

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate