“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Many hoped that the end of 2020 would also mark the end of the crises that marked the year—from the pandemic to an economic crisis and racial inequality. But 2021 has begun with a more infectious strain of the virus, a worsening second wave, another lockdown, and a white supremacist attack.

Pandemics elongate the sense of time, where the first wave seems like a decade ago and the lessons from it forgotten. But the recent history of 2020 is being repeated in 2021, for worse, but also for better. While governments are pursuing the same top-down approaches—from border restrictions that stoke xenophobia to lockdowns that police racialized communities—there are also bottom-up movements building for migrant justice, police abolition, and paid sick days.

From “Chinese virus” to “UK variant”

A year ago a novel strain of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) emerged out of the industrialized global food chain, which was first identified in China. Not surprisingly, after circulating around the world for a year and infecting nearly 100 million people, the virus has evolved new strains. This includes the variant B.1.1.7, first identified in the UK, which is more transmissible. As the CDC explains,

“Viruses constantly change through mutation, and new variants of a virus are expected to occur over time. Sometimes new variants emerge and disappear…Multiple COVID-19 variants are circulating globally. In the United Kingdom (UK), a new variant has emerged with an unusually large number of mutations. This variant seems to spread more easily and quickly than other variants. Currently, there is no evidence that it causes more severe illness or increased risk of death. This variant was first detected in September 2020 and is now highly prevalent in London and southeast England.”

These viruses were initially associated with the geographic location where they were first identified, but the response was racialized. When the novel coronavirus first emerged many politicians and media insisted (against the advice of the WHO) of calling it the “Chinese virus” and “Wuhan flu”—as though it was the direct result of the people, cuisine, culture, or government in China. This fuelled an epidemic of anti-Asian racism that traveled faster than the virus itself—including racist conspiracy theories, online petitions, hate crimes in the streets, and Asian workers facing discrimination at work. Some of the first community organizing in response to the pandemic was from Asian communities around the world challenging the wave of reaction.

Despite the popular term “UK variant”, and despite the greater transmissibility of the new strain, there has rightly been no hysteria about “London flu”, no insulting characterizations about British cuisine, no conspiracies about the British government, no petitions to quarantine British-Canadian students, no attacks on people assumed to be of British heritage, and no discrimination against English-speaking workers. This confirms the racism and irrationality of the response to the original strain of the virus.

Border control or migrant justice?

People should reduce their non-essential travel in a pandemic, but many people’s livelihoods depend on crossing borders. The xenophobic response to the novel coronavirus fuelled a pandemic response more concerned with border control than public health. As the World Health Organization warned last February, “In general, evidence shows that restricting the movement of people and goods during public health emergencies is ineffective in most situations and may divert resources from other interventions.”

As a study in Science Magazine found, the Chinese government’s militarized lockdown of Wuhan only delayed the spread of COVID to the rest of the country by a matter of days, while international travel bans on China only delayed the spread of the pandemic by a few weeks. Italy’s ban on travel from China didn’t stop the virus from overwhelming a healthcare system that had been dismantled by decades of cuts, while Trump’s travel ban didn’t help front-line health workers access basic protective equipment.

Aggressive border control accompanied government apathy towards outbreaks of COVID-19 among migrant workers. This illustrated how border controls fail public health in two ways: they don’t serve their stated purpose of keeping viruses out, but they do serve their intended purpose of maintaining precarious work for migrants. This made migrant farm workers vulnerable to COVID-19, contributed to outbreaks, and undermined public health. Advice to “self-isolate at home” is meaningless for migrant workers who are forced to live in crowded, employer-controlled housing and work even after testing positive for COVID-19.

What did help was not further border controls but migrant justice. Migrant workers themselves articulated more than a dozen policies that would improve their lives and strengthen public health—from status to PPE, and from safe housing to decent work. As a result of months of mobilizing during the pandemic, Migrant Students United stopped mass deportations by pushing the federal government to make post-graduate work permits renewable.

The unmet demands for migrant justice, and the threat of a more contagious variant, means that much more needs to be done to address the pandemic through decent work. But instead politicians are responding to the new strain by a xenophobic focus on borders. While Ontario’s finance minister went on vacation, Premier Doug declared that we are “at extreme risk right now” from “threats coming in from outside, at our borders”, despite travel accounting for less than 0.31% of new cases. The real risk of travel is when workers are compelled to travel through the city and work while sick. But while 30% of all outbreaks are in workplaces, but Ford sees “no reason” to provide sick days.

Policing lockdowns or legislating paid sick days?

People should reduce their contacts during a pandemic. But abstract calls to “stay home” are ineffective without addressing systemic barriers, and enforcing lockdowns through the police undermines public health. The response to the first wave included a partial lockdown and partial supports, to prevent the economy from collapsing. Grocery workers went to work with pandemic pay but without paid sick days, while CERB was temporarily and partially available for those who could not work. At the same time the police were empowered to enforce lockdown measures, and did so in the same way as they enforce everything else: ignoring large crowds of white people not wearing masks (including Toronto’s mayor), while fining and assaulting a Black father who was socially isolating with his child, both wearing masks.

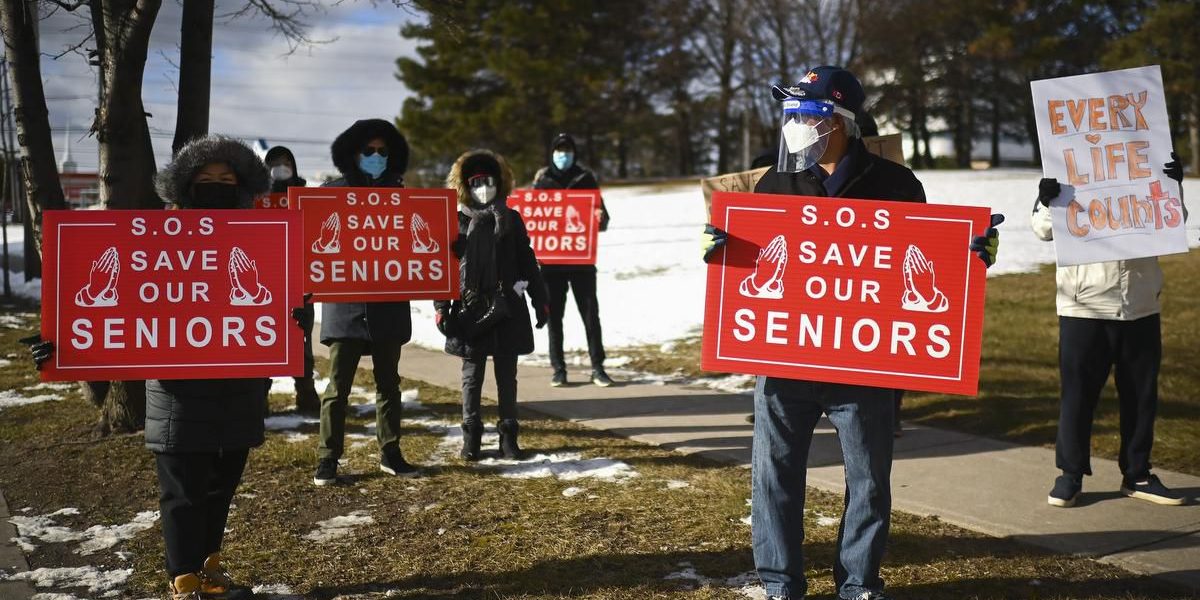

In response the twin crisis of Black people being exposed to death by COVID-19 and death by police, a resurgence of Black Lives Matter in the summer challenged the racist police and the racialization of precarious work. Calls to defund and abolish police and prisons accompanied demands to improve the working conditions that put racialized workers at risk for COVID. This intertwined with growing calls for paid sick days across the country, which gained a boost in the fall when Chief Public Health Officer of Canada, Dr. Teresa Tam, called for an equity approach to COVID—including decent jobs and paid sick days for all.

But billionaire grocery owners cut pandemic pay, the federal government transitioned from CERB to EI (reducing the numbers who qualified), and provincial governments from the NDP in BC to the Conservatives in Ontario still refused to legislate paid sick days. When it comes to enforcing borders (a federal jurisdiction not based in public health), Ford vowed that “If the prime minister doesn’t want to do it, I’m going to do it. I’m not going to put the people of Ontario at risk”. But when it comes to paid sick days (a provincial jurisdiction that is a pillar of public health), Ford has abdicated responsibility—saying “I can’t speak for the federal government, but I’m pretty sure they’re going to extend it,” referring to retroactive income supports that are no substitute for paid sick days.

In response to the second wave, Ford adjourned the legislature early rather than passing the NDP’s “Stay Home If You Are Sick Act” that would have legislated paid sick days for all. Instead he declared a “stay at home” order that yet again empowers the police to enforce a lockdown rather than empowering essential workers to protect their own health. This perpetuates the twin crisis for racialized workers—who are disproportionately denied paid sick days and disproportionately targeted by police. As Hamilton organizer Sarah Jama explained, “Black people and poor people will face the brunt of what it means to be stopped during the pandemic.”

Vaccinate against inequality

The development of safe and effective vaccines, and the start of their rollout in December raised the hopes for ending the pandemic and the suffering associated with it. But a month later it’s clear that pandemics cannot be solved through technology alone. There could paradoxically be more deaths after the vaccine’s development than before—not because it’s not effective but because its distribution has been as unequal as the social and economic factors driving the pandemic.

In the context of mass inequities and an accelerating public health crisis, there are two responses. Guardian columnist Owen Jones summarized the Tory response in the UK:

“around 45,000 people have been fined for breaking COVID-19 rules, with many facing prosecution for failing to pay up…Yet not a single British employer has been prosecuted for violating rules that exist to save lives, and protect the NHS from the tsunami overwhelming it. Operation ‘blame the public’ is in full swing.”

The same operation is being deployed across Canada during the second wave—blaming individuals rather than precarious work, and calling for borders and police rather than migrant justice and paid sick days.

These responses erase the memory of the first wave and condemn us to repeat it. But thankfully, this memory is not ancient history, and it includes another response to the pandemic. It was only a few months ago that the streets were filled with mobilizations to support Black lives and defund the police, and these demands were reconfirmed by the sight of police complicity with white supremacists. Migrant justice organizing has continued through the pandemic, winning gains and allies. After a worsening pandemic and a stronger movement for decent work, the demand for paid sick days is now everywhere.

These movements for social and economic equality, which preceded the pandemic and have grown through two waves, offer real hope. Not only for achieving vaccine equity and ending the pandemic, but also winning a world beyond borders, police and precarious work.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate