On Monday, members of OPSEU/SEFPO and the wider public were made aware of allegations of corruption against the former President Warren ‘Smokey’ Thomas, Vice-president/Treasurer Eduardo Almeida and former financial administrator Maurice Gabay.

The level of alleged corruption is staggering. The three have been accused of unlawfully transferring $5.75 million worth of funds and assets from the union. These allegations come on the heels of corruption scandals at Unifor and CUPE. Not only do these scandals give the union movement a bad name, but they raise serious questions about how and why these scandals happen. For the left, stopping corruption scandals in the trade union movement cannot be separated from the project of building a fighting labour movement from below.

Scandal

The details of the pilfering of union funds by the former OPSEU executives and administrator shows the three have brazenly been stealing from the union to enrich themselves. The three have been accused of taking $670,000 in cash from a strike fund without explanation. Thomas and Almeida are accused of paying themselves lieu and overtime pay to the tune of $488,000 and $360,000 respectively. As elected officers neither Thoman nor Almeida were entitled to any lieu or overtime pay.

Thomas was accused of transferring ownership of six OPSEU owned vehicles to his family. Almeida transferred ownership of two vehicles to himself and Gabay transferred ownership to a close personal friend. Thomas and Ameldia filed harassment and defamation complaints against the executive board that were then settled for $500,000 each. These settlements were unauthorized payouts. On top of this all three racked up charges on union credit cards, that union paid out without any receipts or documents. Ameldia alone expensed, without documentation, over $1.3 million on the union credit card.

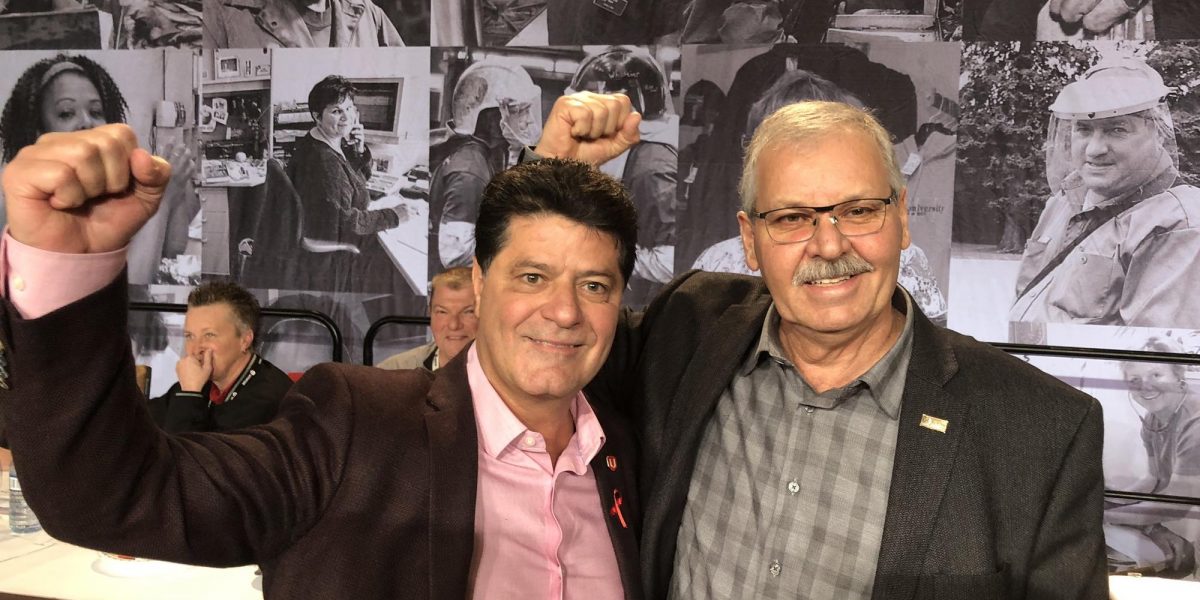

While the OPSEU union corruption scandal is noteworthy for the large sums, it is hardly unique. In 2021 the former head of the United Auto Workers, was sentenced to prison for his part in a wide ranging embezzlement and racketeering scheme that saw the UAW leaders collude with auto company executives to swindle members. In the past year Unifor and CUPE’s largest local have both been rocked by scandals. In March 2022, former Unifor President Jerry Dias was accused of taking a $50,000 kickback from a COVID-19 rapid test supplier to promote the tests to employers of Unifor members. After stepping down, revelations about the lavish and often dubious expenses of some Unifor executives were made public. Also in March of 2022, the President of the largest CUPE local in Canada, CUPE 79, was forced to resign after being entangled in a kickback scheme which involved him receiving $20,000 to appoint his second in command a $46,000 a year OMERS board position.

Corruption of union officials like Jerry Dias and Smokey Thomas often make for big splashy media stories. There is little doubt the corporate media love to make fodder out of “union bosses” engaged in kickbacks or embezzlement. These stories serve to reinforce the corporate narrative that unions are out to swindle workers. They make unions seem like third parties that are no different than any other big institution.

Union corruption in context

But corporations don’t care about workers, because they exploit them every day. Corporations don’t care that union bureaucrats embezzled funds, they much prefer that to seeing those funds used for strikes or organizing. But the corporate press will use these scandals to weaken unions for their own benefits, and to distract from the exploitation at the heart of workplaces.

What sometimes gets lost in headlines about union corruption scandals is that they simply pale in comparison to the routine business swindles and government corruption. The mega wealthy in Canada have stashed over $380 billion dollars in offshore tax havens, costing taxpayers billions of dollars.

In 2021 it was reported that at least 68 Canadian businesses that were earning profits and paying out massive dividends to shareholders had received over $1 billion through the government’s Canadian Economic Wage Subsidy (CEWS). This blatant swindle of the public purse elicited no fines or punishments (the government did see fit to crack down on people who received overpayments Canadian Economic Recovery Benefit).

The relationship between big business and the government breeds a routine almost everyday form of corruption. Big businesses are regularly bequeathed subsidies, tax write-offs, exemptions, and heft contracts. They have a seat at the table when laws are written that govern their interests. For instance, When Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Pipeline construction project was at risk of failing the federal government swooped in to purchase it. The ties between the federal government and the oil and gas sector run deep. This also happens at the provincial level. In Ontario, the Ford Conservatives skirt the rules and take money from developers, for-profit long-term care homes and for-profit medical companies and in turn they pass legislation to help these companies line their pockets.

Loblaws is a perfect encapsulation of the routine corruption that dominates our business class. Over the last decade they have engaged in tax avoidance schemes, fixed the price of bread, received massive subsidies from federal and provincial governments, engaged in egregious pandemic profiteering, controversial all while pushing to lower the minimum wage. The owners of Loblaws have faced no consequences for their actions.

It’s hardly a scandal to hear of business corruption because capitalism is based on exploiting people and the planet. But it is a scandal to hear of union corruption because they exist as a defence against exploitation. The question is then is how have democratic organizations of workers been taken advantage of by union bureaucrats

From compromise to corruption

The reality is that unions, at their core, are the collective power of workers. They are organizations that allow workers to combine and fight for their interests. Of course there are challenges with unions, they are shaped by the power structures of society. Modern unions have developed a strong bureaucracy which tends towards stability and self-preservation. This can tamp down democratic and militant impulses to challenge the big business agenda. Compromise rather than confrontation. The same tendencies in the union bureaucracy that steer towards compromise can also open the door to corruption.

In other words, the corruption at the top of OPSEU is a reflection of how much the past leadership distanced itself from rank and file activity from below.

Thomas’ leadership of OPSEU was from the beginning top-down and unaccountable. It was also devoid of any coherent vision and strategy to fight to improve the lives of OPSEU members and the working class of Ontario. As part of a power struggle within the labour movement Thomas pushed a dues strike at the OFL in 2011. This led to OPSEU splitting from the OFL at a time when maximum unity of the working class was needed. Instead of united rallies against the Liberals’ Bill 115 in 2013, we had separate rallies. Instead of a united campaign to take on Hudak’s threat of right to work – OPSEU was formally outside this effort. This served only to weaken the labour movement.

Thomas’ politics were deeply conservative in the sense he aimed to preserve and extend bureaucratic routinism of the trade union. Thus he could vacillate between working with the Working Families Coalition – a coalition of unions supporting the Liberal Party – and accusing his opponents such as Sid Ryan of not supporting the Ontario NDP enough (at the time the NDP was running on a platform of austerity lite). In the last number of years Thomas’ politics tacked further to the right, going so far as to praise Doug Ford and help bolster his image by appearing with him in public.

His aim was to bargain, compromise and lobby. As he put it, the union should be “advocators not agitators” and that focused on “Consultation rather than just confrontation.” Any rank and file members or leaders who questioned the direction of the union, or who aimed to build rank and file power were treated as an opponent and attacked. A culture of secrecy and unaccountability enveloped the union. The staff were routinely mistreated and the democratic life of the union flatlined.

This is not inevitable, as the recent education workers strike shows. Workers in unions are more than capable of engaging in militant union tactics and defying the law.

Militancy is the best medicine

Corruption thrives when there is no accountability and transparency. The details of the OPSEU scandal came to light as the result of a forensic audit ordered by the executive board in December of 2021, which the three accused tried to scuttle. The wider context for this was an ongoing challenge to Thomas’ leadership.

The scheduled OPSEU convention in the Spring of 2021 was delayed by a year due to COVID. Despite this JP Hornick, the then chair of the College Faculty Bargaining Team and leader of the 2017 College faculty strike, launched a campaign for the presidency of OPSEU. The campaign was based on union renewal, transparency, empowering members and reinvigorating the union to make it a fighting force for workers. It was this campaign that struck fear in the old guard of the union and empowered people to challenge Thomas’ corruption. Thomas chose not to rerun and Hornick’s year-long campaign culminated in a first ballot victory at the OPSEU convention in April 2022.

It is commendable that the newly elected OPSEU leadership – like the new Unifor leadership – is committed to rooting out corruption and ensuring accountability. This is no small task. Sweeping misdeeds under the rug would be a serious mistake. It is true that the best disinfectant is sunlight. But transparency and more stringent reporting rules inside unions are only one side of the coin in combating corruption.

Corruption is more likely to take hold in unions that have developed a business like-culture. Unions that are seen by members and leaders as simply a transactional exchange – members pay dues while the bureaucracy provides services and contracts – leads to a leadership that is unaccountable and ultimately undemocratic. Decisions end up being made behind closed doors and the temptation to cozy up to employers and governments grows.

The best medicine to tackle corruption is militancy. When members are engaged, active and feel part of a collective project that improves their own lives and uplifts their communities, the chances of corruption diminish. The British Miners strike of 1984/5 provides one of the most heartening examples. When National Union of Miners miners went on strike to defend their jobs, their union was hounded by authorities. Not only were the police violently assaulting picketers, but the state was surveilling the union and levied massive fines for an illegal strike and froze their bank accounts. The NUM was forced to run its entire strike on cash funds funnelled across international borders. Despite claims at the time, not one penny was unaccounted for. The opportunity for corruption surely existed, but the class struggle spirit of the union militated against this.

The left’s response to the OPSEU scandal must counter the big business narrative that unions and union leaders are inevitably corrupt. We have to aim to build the confidence and capacity of rank and file members to not only assert themselves in their unions, but to take on the bosses. The best way to prevent union corruption is to build class struggle unionism from below.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate