Is there any good way to redevelop a prison? Some ex-prisoners would rather see institutions demolished than repurposed for the profit and enjoyment of those who were not held captive there. Other survivors have fought hard to transform these monuments of state violence into sites of memory, resistance, and creative engagement.

Members of the P4W Memorial Collective have shared their critique of current redevelopment plans for the Kingston Prison for Women (P4W) as a colonial erasure of memory, and their vision for reclaiming P4W as an abolitionist monument for survival. In this final article of the series, we look at two examples of prison redevelopment that have involved robust consultation and collaboration with survivors of the institution. What lessons can we learn from these examples for the future of P4W?

Holloway Prison, London, England

Holloway Prison opened 1852 in the borough of Islington, North London. After decades of confining men, women, and children, it became the first UK prison for women in 1902. With expansions over time, it became Europe’s largest prison for women. Holloway was rebuilt between 1971 and 1985, maintaining an orientation to confinement and inequality but with a more palatable facade. By the early 2000s, the prison had become a place of squalor with high levels of self-harm among prisoners. In 2007, the Corston Report proposed that fewer women should be imprisoned and institutions like Holloway should be closed.

The closure of Holloway Prison and future sale of the 10-acre site was announced in November 2015. The announcement was made without consultation, and prisoners faced unanticipated relocation far from their loved ones. Islington Council produced the Holloway Prison Site Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) in response to the prison closure. This document provides detailed guidance for the future of the site, and featured consultation with local residents, individuals and organisations in 2017 and 2019. SPD mandated features for inclusion in the development because community groups campaigned hard for them.

Council specified the development must have a minimum of 50% genuinely affordable housing. This would be a mix of housing types, including a significant proportion of family accommodation; social infrastructure such as a “a women’s building/centre that incorporates safe space to support women in the criminal justice system and services for women as part of a wider building that could also include affordable workspace to support local organisations and employment opportunities”; and high quality, publicly accessible green space.

The prison was purchased by Peabody housing association for £82 million in March 2019, with a £41.636 million interest bearing loan, £39 million grant funding from London Mayor’s Office, and approximately £10 million to subsidise the difference between London Living Rent and Council Target Rent. The development is expected to provide 1,000 homes, 42% of which will be “genuinely affordable” (rented at Council target rates), 18% will be shared ownership, and 40% for private sale.

Since the closure of Holloway, local community residents, activists, and former prisoners have been fighting through groups such as Reclaim Holloway to ensure the development is just and accountable. Sisters Uncut occupied the prison and demanded it be used to house survivors of domestic violence. Some have argued that the key agenda of the redevelopment is capital accumulation, not social justice; the sale of Holloway was intended to help fund nine new prisons, though this objective was undermined by an inability to find a commercial buyer.

Community groups are fighting to keep the focus on those who were confined and those continually criminalized. Peabody has responded to these critiques by promising a Women’s Building, created with Islington resident’s input, to provide the support services to vulnerable women. Niku Gupta from Sister’s Uncut says, “It feels like a victory of sorts that Peabody listened. It shows that direct action works. But you never know what can happen with the centre. It could just be all talk by Peabody. We have no reason not to trust them but we are going to keep the pressure on.”

This is not a clear victory. Reclaim Holloway has criticized Peabody’s draft masterplan, which located the Women’s Building on the ground floor of a residential tower. Community Plan for Holloway (CP4H) claims Peabody will not “be able to provide the vision that everybody’s been fighting for since 2016.” Community efforts successfully pushed for the Women’s Building to be located at the front of the development as a flagship. Peabody is currently offering around 1,200 square feet for the building. The Women’s Building will need between 4,000-6,000 square feet in order to meet the needs of women’s organizations.

Space was also allocated in preliminary designs for an exhibition space dedicated to the history not just of Holloway but of women and the criminal justice system. This is a key issue for Reclaim Holloway which the developer acknowledges. Peabody also claims to acknowledge the “rich history of care and stewardship” by prisoner gardeners at the site. They use a “landscape led” approach, which designs around existing trees and integrates existing garden spaces. That said, according to CP4H the site will be levelled and only some of the trees and green space of the former prison will remain. This makes it all the more important for the Women’s Building and exhibition space to mark the history of the site.

Parramatta Female Factory, New South Wales, Australia

The Parramatta Female Factory was Australia’s first purpose-built penal institution for women. The “female factory” was a hybrid institution that combined the functions of a prison, jail, and workhouse, confining women and children in the penal colonies of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land. Parramatta operated as a prison and workhouse from 1821-47, but over the years, other institutions were added to the site, including an orphanage (1844-86), an asylum (established in 1847, now operating as Cumberland Hospital), and the Parramatta Girls Home (also known as the Parramatta Girls Industrial School, which ran for almost a century from 1887-1974. Long before these institutions were built, the land belonged to the Burramatta people of the Darug nation, who continue to steward the land in resistance to colonization.

The youth confined in the Parramatta Girls Home included many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander girls from the Stolen Generations. Girls received minimal education, with a focus on training as domestic servants. Survivors speak of regular coroporal punishment, confinement in isolation cells, sedation, sexual abuse, and denial of food. Most of the perpetrators were never reported or investigated.

Parramatta Girls Home was officially closed in July 1974, but it continued to operate as a Kamballa (Girls) and Taldree (Boys) Children’s Shelter until 1983. In 1980, the Department of Corrective Services took over the main buildings of the Parramatta Female Factory precinct and operated the Norma Parker Detention Centre for Women until 2010.

In 2012, the Parramatta Female Factory Precinct became Australia’s first officially-recognized Site of Conscience, thanks to the efforts of the Parragirls, a network of survivors of the Parramatta Girls Home established by Bonney Djuric, Lynette Aitken and Wiradjuri woman Christina Green in 2006.

A Site of Conscience is a place of memory that helps visitors connect the present to the past in order to build the capacity to prevent violence and abuse in the future. It is a place that invites the public to acknowledge the trauma of oppression and to facilitate healing and social transformation. An example of a Site of Conscience in Canada is the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre in Sault Ste-Marie, Ontario.

The Parramatta Site of Conscience designation grew out of the Parramatta Female Factory Precinct (PFFP) Memory Project, which developed alongside the Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. The PFFP Memory Project “brings together artists, historians, academics and former occupants… to transform this once inaccessible institutional precinct into a place of shared cultural heritage that acknowledges the significance it holds for First Nations people, women, Forgotten Australians, Stolen Generations and in the provision of mental health services.”

The Parramatta Memory Project organizes events, exhibitions, and educational workshops in a gallery and community space established within the former institution in 2013. Co-founder of Parragirls, Bonney Djuric, explains the personal importance of the Memory Project: “I needed answers. I needed to make sense of something that never made sense. To reclaim something of myself that had been taken from me in this place”. She continues:

“Parragirls had to work out for themselves how to tell their own story. This is why they returned to campaign to save the home as a living memorial and how their creative work began; how they came to embark on as a form of concrete restorative justice through art and memory at the site itself, working in tandem with First Nations artists and the traditional owners, the Burramattagal people of the Darug Nation.”

For Djuric, the work of transforming the Parramatta Female Factory Precinct into a Site of Conscience collective “demonstrates the power of art to generate new ways of engaging with injustice, not only to survive its consequences but also to imagine its legacies as an opportunity for change, to stand up and speak out, despite the ‘moral’ risks and the pain of doing so.” Among their many creative projects, the Parragirls have made a 3D immersive film and published a book of collaborative art and writing.

In an article for The Conversation, Djuric and co-authors Linda Steele and Lily Hibberd argue: “Apologies, stone memorials and trauma tourism no longer suffice for those living with the consequences of serious abuse. We urgently need a new imaginary for our past, where we make use of Australian heritage to do justice.”

In spite of its clear historical significance, the Parramatta Female Factory did not become a federally-recognized heritage site in Australia until 2017. The North Parramatta Resident Action Group has been instrumental in gaining this recognition, and unions announced a green ban that would complicate government redevelopment plans of the site. Included in the plans for redevelopment is the Parramatta Girls Home Memorial and Heritage Garden, which has been designed as “a place for everyone, but also a quiet and reflective place for the ParraGirls and their families.” Parramatta North’s current vision for redevelopment includes “social infrastructure to be built alongside new residential, commercial and retail spaces.”

Lessons for P4W

Like P4W in Canada, Holloway and Parramatta were the first prisons for women in England and Australia respectively. Like P4W, these sites featured significant histories of abuse and harm, legacies which continue in operational sites of confinement today.

The ongoing redevelopment of Holloway and Parramatta make it clear that survivors must be full collaborators and consultants in any prison redevelopment project. For Holloway, the community vision would have been incomplete had it not reflected prisoner’s experiences and knowledge, and ensured affordable housing and a Women’s Building. For Parramatta, the land holds such significance for survivors and the Traditional Owners of the land that it became Australia’s first site of conscience. At P4W, as at Holloway and Parramatta, survivors of the institution are the relevant experts whose understanding of the intangible social history of the site is crucial for ensuring that redevelopment meets community needs.

Holloway’s redevelopment offers lessons to us regarding gardens, naming, and strategy. It is an example of a landscape-led project that acknowledges generations of prisoner gardeners. It integrates existing green spaces and trees, such as the London Plane tree on the site. At P4W, there is a large black spruce tree near the entrance to the prison building which holds great significance for the women who were confined there. Peabody, the developer who now owns Holloway, still follows community and former prisoners’ preferences by referring to the site as a former prison, in contrast to the developer of P4W who seeks to rebrand the prison as ”Union Park.” P4W should not shed its name and history so easily.

Holloway also offers lessons around campaign strategies to maintain pressure and attention over an extended amount of time, including creative community-engagement such as CP4H’s art competition launched this month. For women confined at P4W, art has long been an important practice of healing and self-expression, including through the prison publication Tightwire.

Parramatta’s redevelopment offers lessons around gallery space, telling one’s story, and partnership with the Traditional Owners of the land. This is an example of a gallery space operated by survivors of the institution in the actual building where they were confined. In the Parramatta Site of Conscience, survivors have fought and won a space to share their art and stories. Former prisoners at P4W also need a space to tell their own story, on their own terms.

It is all too easy for a prison site to be masked as real estate, or as a heritage building that preserves the tangible heritage of limestone walls while erasing the human history of the people who lived and died there. It is not enough to display artifacts from P4W at the nearby Penitentiary Museum. The museum currently displays a large photograph and fully-uniformed mannequin representing the Institutional Emergency Response Team, without even acknowledging the 1994 raid and strip-search of women at P4W, which sparked a national reckoning that contributed to the closure of the prison.

Any redevelopment of P4W must unfold in collaboration with the Indigenous peoples upon whose land carceral-colonial institutions were built, in direct contradiction to Indigenous legal orders and practices of safety and accountability. In Katarokwi/Kingston, as at Parramatta, Indigenous peoples must give free, prior, informed consent for proposed development of the lands they continue to steward and protect.

The battles around these three sites are ongoing. The redevelopment of Holloway is expected to start in 2022. The gardens are not the focus of struggle, but rather the proportion of affordable housing and the resources committed to the Women’s Building. At Parramatta, there are ongoing pressures for development of the land by the NSW government. The gallery space and designation as a site of conscience are in place, but the land may experience change through development.

Reimagining redevelopment

Beautiful, creative, mutually-supportive relationships can emerge, even from spaces of institutionalized violence and trauma. Memory is not a luxury; collective healing is necessary, both for survivors and for those of us who have grown up protected by state violence, and therefore dependent on this violence for our material, psychic, and spiritual lives.

To follow the lead of survivors in redeveloping institutions like prisons (or choosing not to redevelop them) is not to grant them a special favour but rather to receive a gift that those of us who have never been caged must learn how to receive. This is how we heal from the trauma of relying on state violence for safety and identity: not by renaming a prison as “Union Park” when the basic respect needed for unity is still lacking.

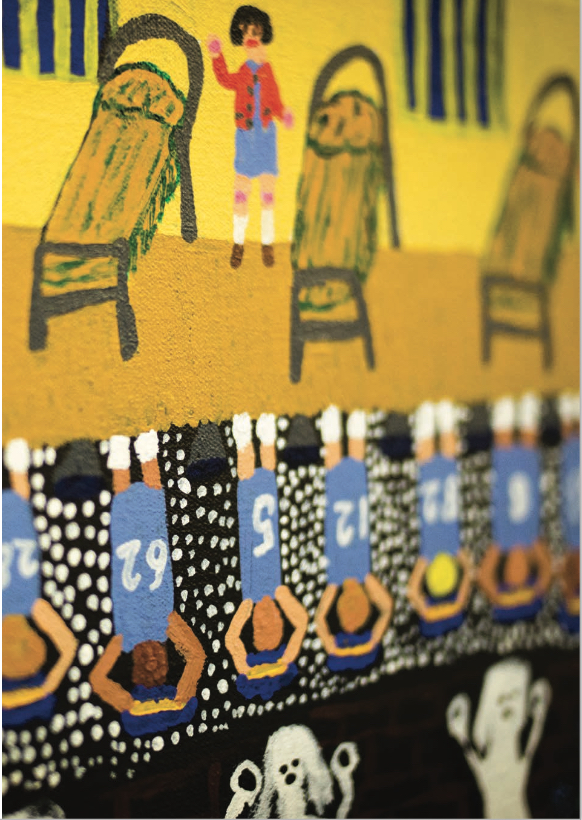

Gypsie Hayes, Scrubbing (detail), 2014. Acrylic on canvas, 30 × 40 cm. Photo: Michael K. Chin, courtesy of PFFP Inc. Photo of Parramatta Girls Home, Australia. Credit, Lily Hibberd.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate