April 7 is World Health Day, and the World Health Organization (WHO) is using the opportunity to draw attention to the deep health inequities revealed by COVID-19 and pandemic responses: “COVID-19 has hit all countries hard, but its impact has been harshest on those communities which were already vulnerable, who are more exposed to the disease, less likely to have access to quality health care services and more likely to experience adverse consequences as a result of measures implemented to contain the pandemic.”

This comes at a time when Canada has surpassed a million cases of COVID-19, and had the “national disgrace” of having the worst record of long-term deaths among wealthy countries. Many have pointed to privatized long-term care as the cause of overcrowding, lack of PPE, and precarious jobs. But these are symptoms of deeper problems. Why are the workers subjected to these conditions disproportionately immigrant and racialized women? Why do the communities they come from have disproportionately high rates of COVID-19 infection and death? Why has the response to the LTC crisis been to spend 10 times the amount of security guards outside LTC rather than on supporting workers inside LTC?

The WHO is “calling for action to eliminate health inequities…to build a fairer, healthier world.” But inequities in vulnerability, exposure to disease, access to healthcare and adverse containment strategies can’t be reversed without addressing the health threat of prisons, borders and police. Fortunately the abolition movement is pointing towards healthy alternatives.

Vulnerability to disease: the legacy of colonization and slavery

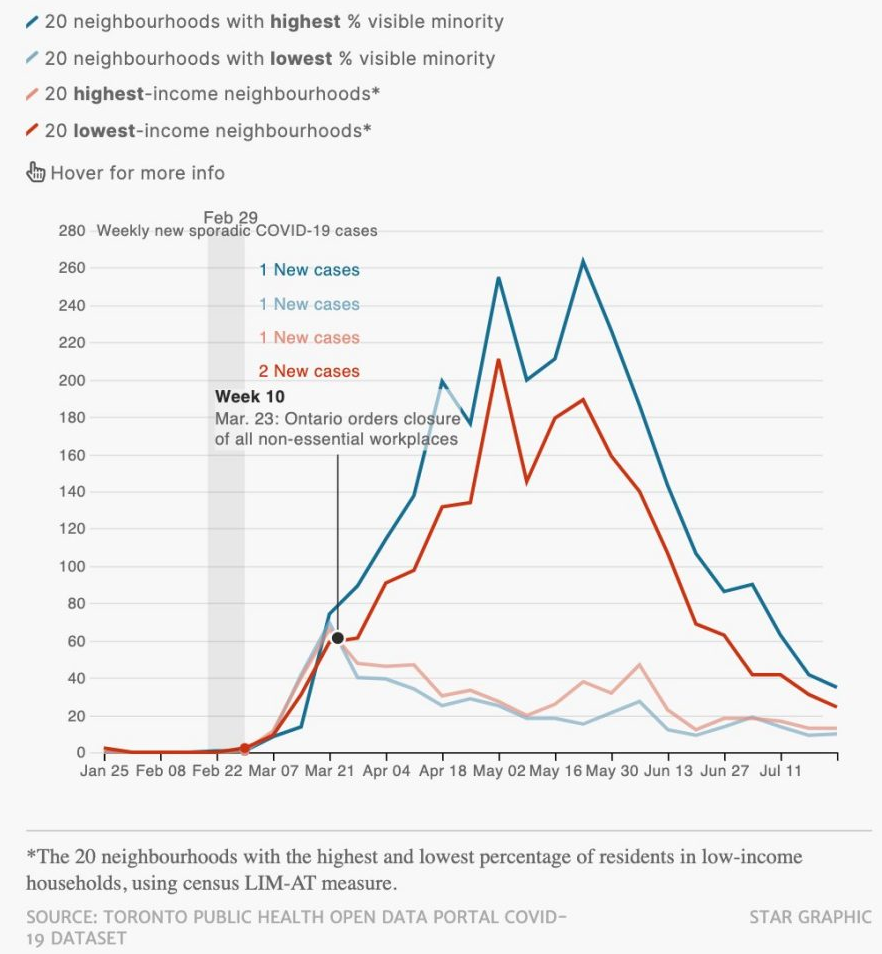

COVID-19 has had a disproportionate impact on Black, Indigenous and racialized people—who are half of Toronto’s residents but more than 80% of COVID-19 cases. Across Ontario, people living in the most diverse neighbourhoods have three-times the rate of COVID-19 infections, four-times the rate of hospitalization, four-times the rate of ICU admission, and double the mortality rate. This is not because of inherent vulnerability to disease: as Public Health Ontario explained, “Structural factors, such as colonization, racism, social exclusion and repression of self-determination are important structural determinants of increased COVID-19 risk, for example in Indigenous and Black populations in Canada.”

For thousands of years there was no carceral state on Turtle Island. But in 1835 the British colony of Upper Canada opened a penitentiary on the land it called Kingston, and imposed British law. The subsequent emergence of the Canadian state has been associated with the railway, but colonial nation-building required prisons and police. As the Canadian Encyclopedia documents:

“By 1867 Saint John, NB, and Halifax, NS, also had penitentiaries, and in 1880 Dorchester penitentiary was built in the Maritimes. The penitentiaries of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, now part of Laval, Qué (1873), Stony Mountain, Man (1874), New Westminster, BC (1878), and Prince Albert, Sask (1911), completed the chain of fortresslike prisons across Canada.”

After the Indigenous sovereignty movement of 1869, the Canadian state also formed the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP, now the RCMP). As Indigenous scholar Howard Adams explained:

“The Indians, who had lived in the area for thousands of years without police, saw no reason for the establishment of a force in the Northwest since there was no serious disorder or lawlessness in the country…The Mounties were not ambassadors of goodwill or uniformed men sent to protect the Indians; they were the colonizer’s occupational forces and hence the oppressors of Indians and Métis.”

When Indigenous peoples again asserted their sovereignty in 1885, the NWMP crushed the movement and the Stony Mountain prison incarcerated its leaders—including Métis leader Maxime Lépine and Cree Chief Pihtokahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker). Today land dispossession continues: more than 60% of prisoners at Stony Mountain are Indigenous, and this was the jail with the largest COVID-19 outbreak—with nearly half of prisoners infected. Another major COVID-19 outbreak was at the Saskatchewan Penitentiary, built on the site of a former residential school.

Canadian prisons and police also continue the legacy of slavery. As Robyn Maynard explains in Policing Black Lives: State Violence from Slavery to the Present:

“Incarceration had replaced enslavement as a legal means to literally strip people of their freedom, as well as separate families and inhibit future employment opportunities. Black incarceration was thus highly effective in maintaining Black disenfranchisement and subjugation in post-abolition Canada. The association of Blackness with danger allowed for the policing of Black peoples’ lives by white settler society, law enforcement and immigration agencies.”

The racialization of poverty and precarious work, the criminalization of drug use and sex work, and racist policing contribute to the disproportionate incarceration of Indigenous and Black people, and increased vulnerability to COVID-19 and other illnesses.

Exposure to disease: border control

Canadian border control is another colonial institution that denies Indigenous sovereignty and continues the legacy of slavery by maintaining a pool of highly exploited workers. As Maynard explains:

“While race could no longer be openly used to deny labour rights to non-white workers, immigration status would serve the same purpose. Canada’s temporary work programs provided an updated means of enforcing Black economic precarity and the exploitation of Black labourers in a way that closely mirrored the conditions of Black enslavement.”

Canadian officials have claimed that closing borders was a public health response to the pandemic. But the longstanding precarious working and living conditions created by border policies actually fueled COVID-19 outbreaks. Migrant farm workers—disproportionately Black and brown—are denied minimum wage, subjected to wage theft, and have inadequate access to food. They are forced to live in cramped housing conditions that prevent physical distancing, and some have been forced to work even after testing positive for COVID-19. They are subjected to surveillance and denied access to healthcare. Underlying all these unhealthy conditions is the denial of status, which prevents workers from asserting their labour rights for fear of deportation.

As Migrant Workers Alliance for Change explained, the pandemic response of the Canadian state was not to support migrant workers in order to prevent infections, but rather to impose quarantine measures that simply contained COVID-19 within migrant communities:

“Under the current regime in Ontario, migrant workers are to be monitored to ensure that if they arrive in Canada infected, those infections do not spread into the community. COVID-19 related measures have not been designed to ensure that migrant workers are themselves protected from risk of infection. That no precautions were provided for migrant workers prior to travel and that governments took no measures to ensure farm workplaces were prepared for workers’ arrival speaks to the appallingly low priority given to the health and safety of the workers themselves.”

Less access to health: over-policed and under-vaccinated

Those same communities that are disproportionately vulnerable to COVID-19 and disproportionately exposed to the virus are also disproportionately denied healthcare including the COVID-19 vaccine. Prisoners have gone on hunger strike for basic PPE and cleaning supplies, and are now facing barriers accessing the vaccine. Federal Conservative leader Erin O’Toole stated that “not one criminal should be vaccinated ahead of any vulnerable Canadian or front line health worker.” But denying the vaccine to a caged population exposed to COVID-19 amounts to a death sentence. It also ignores that prisoners themselves are “vulnerable Canadians”, and are disproportionately drawn from the same communities as many front line health workers.

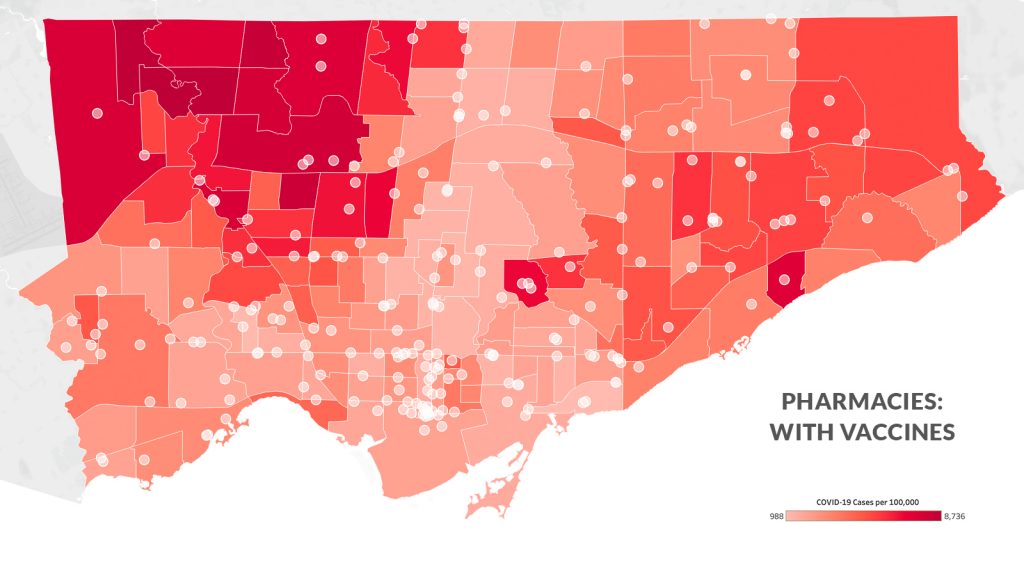

The feigned government support for vulnerable populations and front line health workers has been exposed by the appallingly slow and unequal vaccine rollout. As Akwatu Khenti, chair of Toronto’s Black Scientists Task Force on Vaccine Equity explained in February, “The reason that Black people have a higher rate of positivity, or higher hospital rates, is actually because of social inequities, systemic racism and neighbourhood vulnerabilities…The most vulnerable should be first in line [for the COVID vaccine.] Right now, the most vulnerable are racialized health professionals, racialized communities.” But instead of promoting health equity, vaccine distribution has reinforced inequity: the neighbourhoods with the highest rate of COVID-19 have the least access to pharmacies with the vaccine.

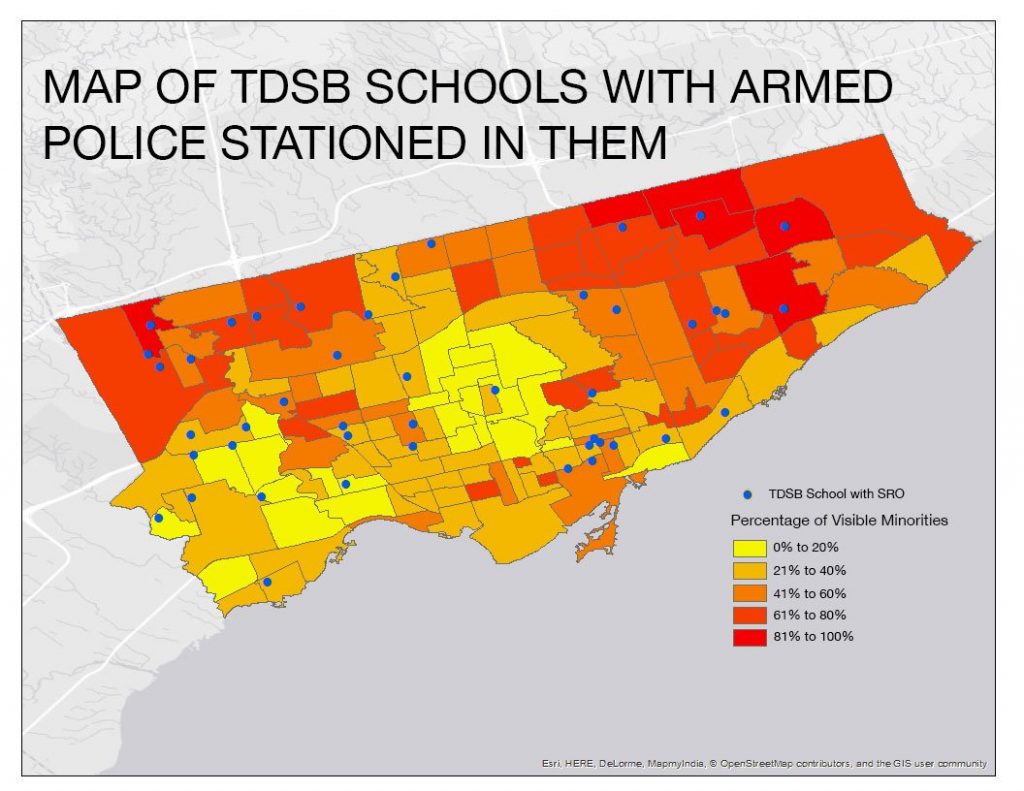

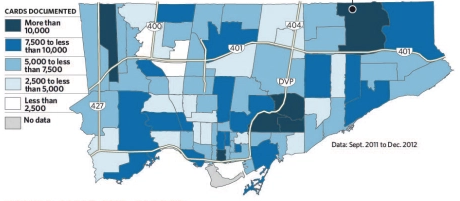

This is not because these neighbourhoods lack pharmacies and lack the capacity for vaccine distribution, but because they were not selected for vaccine distribution. This is also not because they lack state resources: these “vaccine deserts” are full of police. So public resources are deployed to poor and racialized communities, but in the form of state police forces rather than community health. As the maps below show, the same neighoubourhoods with high rates of COVID-19 that have been left out of vaccine delivery are the same racialized neighourhooods targeted by police through “School Resource Officers” and carding. This explains some of the “vaccine hesitancy” among LTC and other front-line racialized workers—who are rightly suspicious of state intervention given its record, who have been denied PPE but are now told to get vaccinated, and who have no paid sick days to actually get the vaccine and recover. As one health provider summarized, “vaccine hesitancy is a scapegoat for structural racism.”

Carceral containment

By ignoring structural inequities, containment measures like quarantines, lockdowns and stay-at-home orders have further widened the health gap of the pandemic. While stay-at-home orders were effective at encouraging many in affluent predominantly white neighbourhoods (who are at low risk of COVID-19) to work safely from home, they did nothing for poor and predominantly racialized neighbourhoods (who are at high risk of COVID-19). When front-line workers have to take crowded public transit into crowded essential workplaces, without recourse to paid sick days, so-called lockdowns or stay-at-home orders do nothing.

Not only have they failed to protect vulnerable communities by not addressing the structural determinants of health, but containment measures have become another tool of the carceral state. For prisoners, pandemic response during the first wave included the beginning of decarceration that promoted health, but this has been replaced by lockdowns within jails—which keep prisoners in their cells for almost 24 hours a day, a form of solitary confinement that harms physical and mental health. For migrant workers, quarantine measures resulted in increased medical surveillance without medical care, and there are concerns that vaccination could lead to deportation.

The same carceral containment is at the heart of the crisis in long-term care, which perpetuates the gendered history of anti-Black racism in domestic service. As Maynard explains, “Black domestic workers were often paid less than minimum wage, subjected to long hours and forced to work while ill, as well as enduring racial slurs and other forms of harassment…The conditions of the allowed for a continuation of surveillance practices that were instituted under slavery. The uninterrupted scrutiny of enslaved domestics by white households was, after all, one of the earliest forms of racialized surveillance.” Similarly, the disproportionately racialized women who work in LTC are paid low wages, denied paid sick days, and during the pandemic are subjected to heightened medical surveillance rather than improved labour conditions. While the Ford government spent $4 million to hire additional PSWs inside LTC, it spent 10 times that amount to put security guards outside to LTC. As Queen, a care worker without status, revealed to Spring Magazine,

“As of last November 2020 any private caregiver that tested positive in the first wave had to be subjected to weekly testing. Refusal means you won’t be allowed to work and cannot enter the building… Testing LTC workers three times a week does not improve working conditions. What it does is add more stress to the work environment and takes away precious time that could be spent mentally/physically recuperating for the next shift of work.”

So the response to the LTC crisis—which is rooted in the exploitation of Black women and a legacy of Canadian slavery—is medical surveillance and security guards rather than providing well-paying full time jobs with paid sick leave.

Health through abolition

As the WHO explains, “health inequities are preventable with strategies that place greater attention to improving health equity, especially for the most vulnerable and marginalized groups.” This is exactly what the abolition movement is proposing, by reversing state policies that marginalize and create vulnerabilities in the first place, and by transforming living and working conditions. As Doctors for Defunding Police stated, “policing is a public health crisis… We can no longer choose to ignore the urgent need to defund the police to advance health equity for Black and Indigenous communities.”

If prisons have dispossessed Indigenous communities from their land and made them vulnerable to disease, then decolonization and Indigenous sovereignty can lead to healing. If the Ontario government is spending an additional $500 million on prisons which disproportionately cage racialized people, then the same resources could support decarceration and safe housing. If border policies exploit migrant workers and fuel the pandemic, then as Chief Medical Officer of Health Teresa Tam explained, “we need to ensure good pay and conditions for every worker along the food production chain, while also addressing the specific needs of temporary foreign workers”—especially status for all.

If Toronto police spend $1 billion to criminalize and police racialized communities, then decriminizing drug use and sex work and defunding the police could provide resources for community-led vaccination, addictions and mental health support, and other health initiatives. If LTC homes have made millions from precarious work that fuels the pandemic, then the money is there to provide racialized women with full-time permanent jobs with good pay and paid sick days.

The national disgraces of LTC deaths and other COVID-19 inequities are rooted in the disgraces of genocide and slavery on which this nation was built, and which are perpetuated through prisons, police, borders and carceral policies. For this year’s World Health Day, we should contemplate the question that Robyn Maynard puts towards us: “what would it look like to disinvest the incredible amount of public funds that are currently diverted toward police and prisons and invest, instead, in community-run, community-based institutions that serve people’s very real need for security, education and dignity?”

Sign and share Choosing Real Safety: a Historic Declaration to Divest from Policing and Prisons and Build Safer Communities for All

Join the Spring reading group for Policing Black Lives, starting April 15

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate