Semir Bulle is past-president of the Black Medical Students Association at UofT and co-founder of Doctors for Defunding Police. Spring Magazine spoke with him about the efforts to diversify and decolonize Medicine, how racism shapes the COVID-19 pandemic, and why a safer and healthier society requires defunding police.

You’re been part of the growth of the Black Medical Students Association and help found Doctors for Defunding Police. Can you explain the rise and interaction of these groups?

In 2016 there was only one Black student admitted to UofT medicine, in a class of 260, and she was the valedictorian. With that, there was a lot of push in the community to have BSAP (Black Student Application Program), my class was the first cohort of that and there are 15 of us. So with that we had a lot of community involvement, we’re indebted to the community that made this happen for us.

So we started holding events. One thing was the Black mental health speaker series, which really took off. And we started attracting hundreds of people to talk at our events, and become a big community hub. We had other events, like med school 101, we started mentoring dozens of kids and became ingrained in the community in our first year. And then March 2 was the first Black Mental Health Day in Toronto, and we held an event because John Tory wouldn’t do anything. You can’t call it a day and then not do anything, so we decided to hold an event that day. We had an event at UofT and sold 700 tickets, so we were really touching the Black community and allies.

And then COVID hit, and the work we were doing before pointed to which doctors were also in the same field. We’re all doing community work in different areas: Naheed [Dosani] doing work with respect to homelessness, Nanky [Rai] with HIV and addictions, we’re doing Black health, and Suzanne [Shoush] Indigenous health. And if we bring it all together, maybe we can have a strong voice.

The police is a humongous issue, and it wasn’t even an issue we had to debate. Every day everyone has interactions with the police, professionally and non-professionally, especially when we work with vulnerable populations. You can just ask if people have had bad interactions with the police and you get dozens of stories. The more vulnerable the person the more likely they had bad interactions with the cops. So we kept organizing, trying to connect our struggles, trying to be as loud as possible.

Doctors are often not considered political, but now over 600 have signed onto Doctors for Defunding Police. Why have so many health providers felt the need to speak up for defunding the police, and what’s the connection to broader organizing?

The name seeming absurd is the point: why has medicine been so apolitical for so long? We’ve been part of the colonial establishment, we can’t just say that we’re a third-party and that the police are abusing our patients—we’re the ones calling them half the time. We can’t pretend the emergency rooms aren’t calling police officers, and nurses and doctors aren’t working in concert with them, or the emergency psyc wards, or in the streets. We can’t just say that these people are separate from us. Medicine has a huge role in this because we perpetuated the violence, so if we don’t take a role in actively stepping back and healing the violence towards these communities then that’s just irresponsible.

We’re getting calls from doctors from Vancouver, from Montreal, engineers from different areas, nurses. It’s not just doctors. It’s a moment in time when a lot of people are fed up with the systems that they see. Everyday we go to work in a system that sees our patients get abused. We see the same communities get worse and worse over time, and we want to see better. Medicine knows it has a role in this, and what role it has in the future is completely up to us.

And medicine itself is changing. In school we’re always told we all belong, it’s about social justice, about belonging to a community. But when we come out and see how medicine is, it doesn’t seem as though it’s as connected to the community. The OMA [Ontario Medical Association] was the biggest non-party spender in the last election where Doug Ford was elected, so why are we told something and then given something else when we go into the medical field. The cognitive dissonance is something that we’re trying to destroy now. If we’re doctors then we’re the healers of society, and if we’re the healers of society then we really have to care about the incomes and how people live when they step out of our offices.

The institutions are a wall, they’re not going to be our allies in this fight. When we organized Doctors for Defunding Police we went to all the CEOs of the hospitals to get them behind this before we came out—and obviously they didn’t want to join. The idea that they’re going to be the first to adopt this is not going to happen. So we need to start leading on these topics. The literature is out there. There have been decades of organizing and people doing this work, and all we’re trying to say is that we should shine a light on the work that’s being done. Our space isn’t to take up other people’s positions, it’s to amplify the community because as doctors we have some social privilege that’s not really deserved. There’s no reason to listen to me, as opposed to the kid I was three years ago saying the exact same stuff—but now people listen to me much more. It’s privilege and we have to do what we can do with that privilege and responsibility.

How is defunding the police part of making society safer and healthier, and why is it important for health providers to be part of the call for defunding police?

The police in Toronto have a $1.2 billion budget, which is 10% of the budget. Black people in Toronto are 20 times more likely to be shot that white people. The police are pointed at certain communities. I’m a Black person and grew up in the northwest corner of Toronto, and the police terrorized me growing up. I remember getting carded over a dozen times when I started driving. You wouldn’t believe what they do to those communities because there’s no oversight.

So you have a bunch of communities that don’t trust the cops, that don’t believe in them. If we don’t trust the cops we have no safety here, this causes mental distress, this causes societies to be torn apart and they have nowhere to turn. It’s a mental health crisis, it’s a physical crisis. And what we’re saying is we’re not going to give you any help, any finances, we’re going to give you more cops. Every time we add more cops, it’s been the same for decades. We can’t even get a 1% raise for nurses, but they raise the police budget 4% every single time. They got $51 million more for cameras.

This stuff doesn’t work, and if healthcare doesn’t intervene it’s negligent towards our patients. We work with these communities every day, and if they go home and are experiencing that and it diminishes their quality of life, then we have to stand up for them.

In response to stats showing that racialized people in Toronto make up 83% of COVID cases, some have called race a “risk factor” for COVID. But as you and other founders of Doctors for Defunding Police pointed out, “race does not determine health outcomes—racism does.” Can you elaborate?

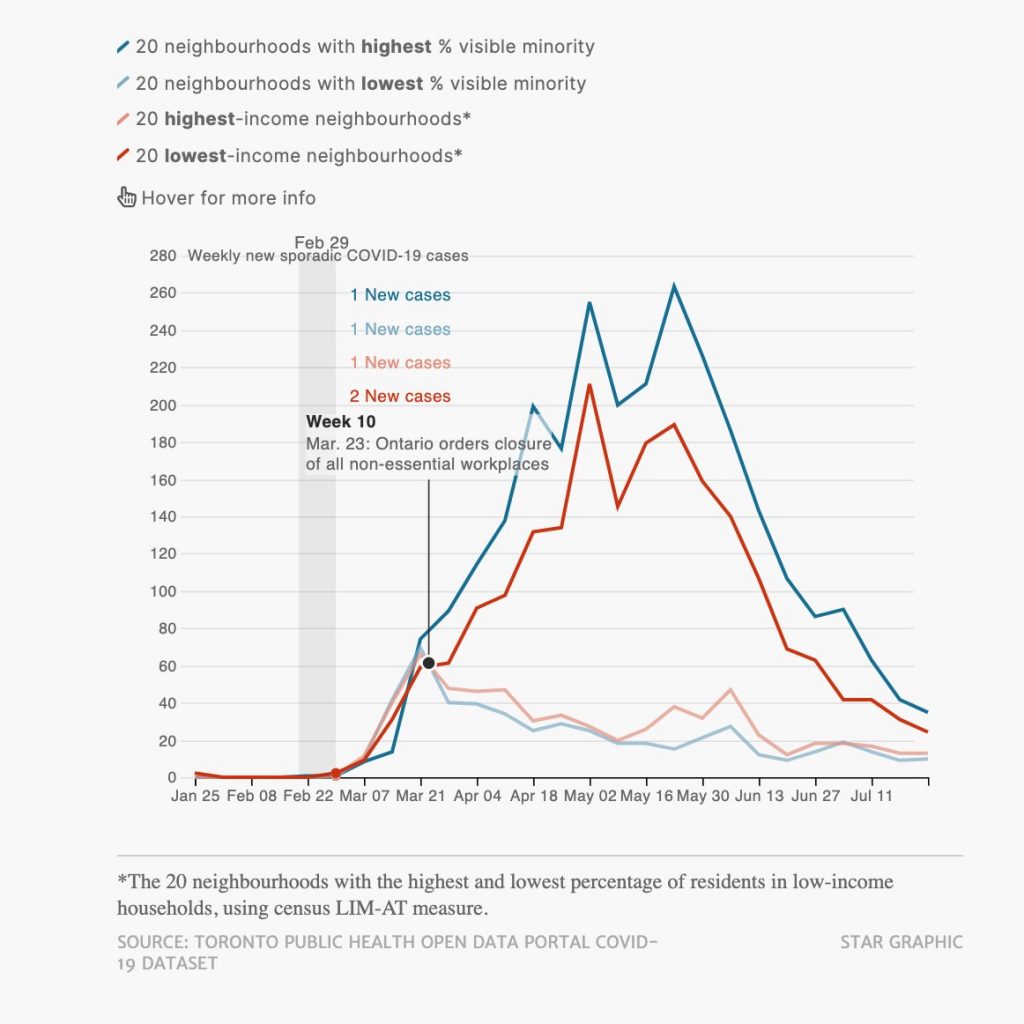

COVID outbreaks were mainly in the racialized parts of the city—so the northwest part of Toronto, and Scarborough. When the lockdown happened on March 17, the only line that goes down is the white rich community that had the money to stop working. The conditions that you’re subjected to are based on a lot of historical factors that leave you in situations where you don’t have anything to protect you. That’s what systemic racism is. These communities are much more vulnerable when these things happen, their environment is so detrimental: people having to work consistently, having to live on top of each other, not being able to socially distance, those are the reason why those areas have spikes.

We have to stop pretending there are two streams. We learn it like that: there’s the social determinants of health, and the biological determinants of health, and we don’t know how much is which, environment is some and genetics is some, and we have to pretend to play the line. But if I took a kid in the poorest situation and gave him all the resources to survive, he would definitely do substantially better. In the Toronto District School Board, a report came out showing that 42% of Black students are suspended at least once before they graduate. They’re criminalized even before they get a chance to get out of there. So what do think happens when we have systems that perpetually put a group of people down every single time, it keeps the system going. It’s not ok, and we need to uproot it to get to the end of the problem.

Medicine has a long history of racism and colonization, including psychiatric justifications for slavery. But there’s also a long history of activism within medicine, including Black psychiatrists like Frantz Fanon. As a Black medical student interested in psychiatry, what challenges and opportunities do you see to transform medicine.

The Black community hasn’t trusted the healthcare system because our outcomes are so much different. Racism is consistent and embedded in medicine. In the 1960s during the civil rights movement, they used to lock people up at CAMH for “protest psychosis”—for Black men believing in civil rights—and that turned into schizophrenia. There’s a study that came out: Black newborns are three times more likely to die when being treated by a white doctor. We still have textbooks coming out saying Black people feel pain differently, or their GFR [kidney function] needs to be adjusted for muscle mass.

Dismantling from the inside is the most interesting thing—the absurdity of a psychiatrist coming out against the medical establishment when psychiatry has been used these ways. What draws me to psychiatry the most is I think, if used properly, it could be the best art and the best healing device, because the mind is so infinite. But right now it’s used to institutionalize people, so why would a Black person ever go into psychiatry? Everyone where I come from has PTSD, and no one is going to talk to the psychiatrist because the second you talk to them they’re going to call the police on you. It’s ridiculous that these systems exist in the ways that they do, and we have to break them from the inside.

Medicine has to change. Medicine right now is still a colonial, racist practice. And if we look at it as anything other than that, which has unequal distribution of health, because that’s what’s currently happening, then we’re complicit in the system. That’s what we need people to understand. Medicine has to move forward in a way that puts the people with the least as the focus. What else is medicine for, if not to help people?

September 30 is a student strike against anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism in the education system, with demands that include supporting Black and Indigenous students, staff and faculty, and defunding police. From a health perspective, why are these important?

Everything is connected, we can’t keep looking at these systems as silos. The police are one of the biggest data apparatus, while healthcare, education and social work has been defunded over the past 30 years. These things go hand in hand, and society has bigger inequities than ever. If we’re not looking at these circumstances as things that can be solved together, with all other groups, then we’re never going to solve them. So when we have a student strike coming up—talking about defunding the police, and educational goals, and goals they want in their communities, and how they want to be funded, and jobs, and what they think they deserve—it’s beautiful.

It’s about intersections, and saying that if we don’t cross all barriers, then none of them will succeed. They can only defeat us easily when we’re in silos—if we’re just fighting for defunding police, and everyone else is just fighting for healthcare, and we don’t work together when it comes to mental health situations that can affect all of us. We’re one progressive group, we’re one force, and if we can have similar goals then we can see a better humanity come out of this. We need people to understand that we’re stronger together, and we’re moving forward.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate