A recent edition of CBC’s The National featured psychiatrists discussing mental wellness during the COVID pandemic. The participants emphasized the importance of seeking out mental health services: “Contact your health provider, family doctor or mental health hotline,” said Dr. Thomas Unger of St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto. “If you’re too despaired, please get checked out.”

Dr. Unger’s advice is, of course, important. Individuals should always seek out appropriate mental health services when they need it. Yet, his comments provide us with the opportunity to critically examine the state mental health care in Canada, and to recognize that there is a pre-existing inequality gap that austerity measures threaten to worsen.

The gap in access

To start, not all those who require mental healthcare in Canada can access it. The Canadian Community Health Survey, administered by Statistics Canada in 2018, included questions on perceptions of mental health care access. It found that only almost half of those who required mental health services did not have their needs fully met. While few reported that their needs for psychiatric medications (such as antidepressants) were unmet, a third had unmet needs for counselling or psychotherapy. An inability to pay was one of the most common reasons provided for this gap.

As with all Canadian health care, the mental health system is multi-tiered. Provincial insurance plans cover billings from physicians and psychiatrists but not from allied providers such as psychologists or social workers. While publicly insured psychotherapy does exist in Canada (e.g., in hospitals or in community agencies), most therapists work in private settings and expenses are covered by private insurance or out-of-pocket. This tiered system has produced a disparity in service access, as private therapy can be cost-prohibitive for working-class individuals and families. Even those who have private insurance may still find it lacking. For instance, private insurance may have caps which are too low to cover the full expense of treatment.

In 2019 Mary Bartram of McGill University found that people with lower-incomes were more likely than those with higher-income to rely on publicly insured services (e.g., GPs and psychiatrists), and less likely to use psychologists and counsellors. This helps to explain why the need for pharmaceuticals, prescribed by GPs and psychiatrics, are largely met while the need for counselling, mainly provided by psychologists and other counsellors, goes unmet. The gap is especially acute for rural and northern communities. And for newcomers, racialized, Indigenous and transgender people, it is compounded with other barriers to access (e.g., racism, transphobia, or lack of language services). The economic crisis in the midst of COVID-19 worsens these pre-existing inequalities.

Economic crisis, mental health crisis and violence

Economic and social inequality do not just create a gap in accessing mental health services, but also themselves create mental health crises. According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, “losing stabilizing resources, such as income, employment, and housing, for an extended period of time can increase the risk factors for mental illness or relapse… Jobs in today’s labour market are increasingly temporary and/or part-time, often with no benefits and inadequate pay… The inability to access affordable housing increases a person’s risk of homelessness. Being homeless, in turn, increases a person’s risk of developing mental illness.”

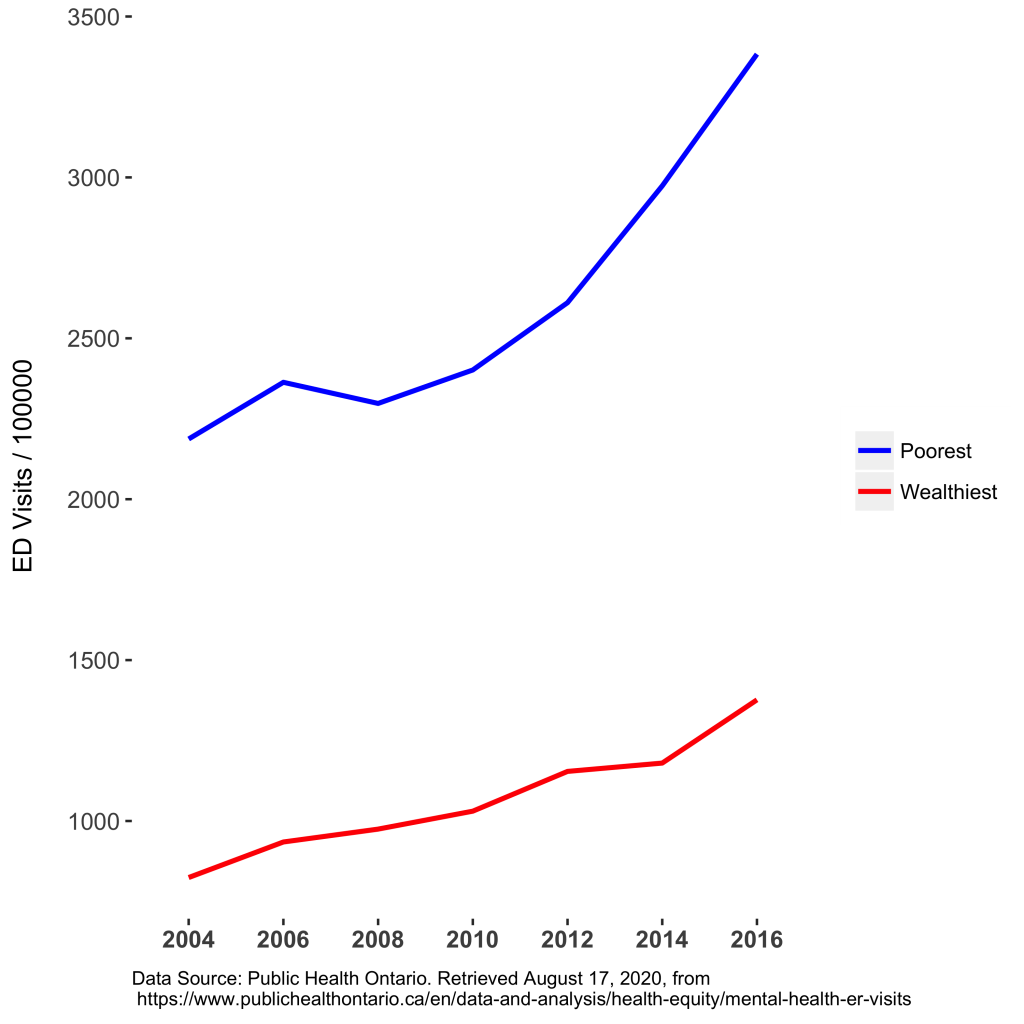

While this creates greater need for mental healthcare, the service gap creates longer wait times and a strain on pre-existing resources. While there aren’t reliable statistics on the typical wait time for mental health care in Canada, it is estimated to be at least several months. A report by Children’s Mental Health Ontario found that youths waited an average of 2 – 3 months for services, with some waiting as long as 2.5 years. The lack of available care in poor and racialized communities means that individuals experiencing mental health concerns have poorer outcomes and reach the point of crisis before finding help. Emergency departments (EDs), therefore, often serve as the first point for psychiatric treatment for individuals who can’t find treatment in the community, and the inequality gap is visible in ED use. For example, as Figure 1 shows, ED use in Ontario is increasing annually across the board, with the poorest people utilizing EDs for mental health concerns at a much higher rate than the wealthiest (i.e., approximately 2.5 times more often). A lack of mental health services is not the only explanation for the difference in ED visits, but it’s an important one.

Figure 1: Ontario Mental Health ED Visits Per 100000 People.

Without supportive services for those experiencing mental health crises, police fill the void. When economic and social inequality both create mental health crises and deny access to mental health services, and an institution based on colonialism and racism responds, “wellness checks” become deadly—illustrated most recently in the police killings of Ejaz Choudry, Regis Korchinski-Paquet, Chantel Moore, and Rodney Levi. As Muhammad Choudry explained after the police shot and killed his uncle Ejaz, “This system is not meant for us. If you’re in a mental health crisis and you’re facing armed people with body armour instead of people who want to listen and show compassion…There was no attempt to help a 62-year old man with schizophrenia. How many more killings do we need to have until there’s a change?”

System change

The proposal to expand access to mental health services is not a radical proposal, nor is it even a new one. Take, for instance, the Mental Health Commission of Canada who, in 2017, put forward recommendations that included increasing access to therapy by increasing public funding. In the past several years, governments across Canada, including the Government of Ontario, have done just that. Additionally, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, both public and private funds have helped to establish virtual counseling services—important resources that can potentially meet the needs of low-income families and those in remote communities if services are equitably distributed. But even if they are, it is unclear whether these additional resources can meet the demand given the increase need which the pandemic has created.

In addition to the demands for universal pharmacare and dental care, a Left vision of healthcare should include publicly insured and more integrated mental health services. These services should be available without any out-of-pocket expense to individuals or families. They should also be developed in innovative ways that reduce barriers for access, including stigma and geographic disparities. Mental health services are not a luxury and we must ensure better access for working-class individuals and families.

A Left vision of healthcare also needs to challenge the social and economic policies that worsen mental health, and empower communities to address them. We already know that by increasing unemployment and homelessness and disrupting health services, recessions worsen mental health. Yet the dominant response to the pandemic is to do just that—from the federal Liberals cutting people off CERB, the Ontario government investing $500 million in prisons rather than homes, to the City of Toronto resuming evictions.

Supporting mental health needs to include raising the minimum wage and reducing precarious jobs, building affordable housing rather than jails, and defunding the police to support communities. As Doctors for Defunding Police state, “we have come together to stand in solidarity with calls from Black and Indigenous communities to address systemic anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism, defunding the police, and reallocating funds to support response systems backed by public health research.”

They call for defunding the police with reallocation towards: “a) the creation of new community emergency services to support the mental health needs of Black, Indigenous, racialized, disabled, poor, and other community members made vulnerable by structural violence. b) the creation of non-police response teams trained in de-escalation and crisis support who root their work in transformative trauma- and community-informed practices.”

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate