On October 3, 1909, American labour activist Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was arrested in Missoula, Montana. She was leading a campaign of civil disobedience across the American West that united demands for workers’ rights with free speech advocacy. These “free speech fights,” as they became known, inspired generations of socialists to identify free speech rights as a key part of the class struggle.

116 years later, free speech remains a political battleground. By looking at how Flynn and her comrades in the International Workers of the World (IWW) won the free speech fights in Missoula, Montana and Spokane, Washington, we can learn to better organize against state repression and in defence of civil liberties for the working class.

A born radical

Born in 1890 to Irish-American parents, Flynn spent her formative years in New York City, where she gave her first public speech—”What will socialism do for women”—at age 15. At 16, she began “soapboxing”: an agitational public address traditionally delivered from a soapbox on a street corner. Before long, she gained a reputation as a passionate speaker with a knack for making her message clear and accessible.

In 1907, she joined the IWW as a full-time organizer. The IWW had been formed just two years earlier in Chicago, and it represented a bold new strain of industrial unionism. Unions at the time tended to be trade unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labour (AFL). The AFL was narrowly concerned with winning good contracts for its workers while preserving the capitalist system, and it tended to act as a conservative bulwark against working-class radicalism.

In contrast, the IWW acknowledged that the working class has fundamentally different interests than the capitalists. They organized workers based on industry instead of trade and promoted solidarity between workers of all occupations, an idea they encapsulated in their slogan: “An injury to one is an injury to all.” Unlike the AFL, which discriminated against women, Black, and immigrant workers, the IWW preached “One Big Union” and saw the power that lay in a united working class. Flynn quickly gained organizing experience in strikes along the East Coast.

Missoula

At the time, the IWW’s model of industrial unionism was winning over workers in the American West. Large populations of itinerant workers and their families, many of them recent immigrants, flocked to the boomtowns that had sprung up around the mining, forestry, and agricultural industries.

Missoula, Montana was a hub for the Pacific Northwest, and workers came from across the country to seek employment in surrounding mines and lumber camps. The local labour market was monopolized by employment agencies: labour brokers that held exclusive deals with companies in the area.

Any worker seeking a job would have to go through these “job sharks”, as they were called. Usually they had to literally buy a job from the agency in the form of a “letter to the boss” that allowed them to work. Since more new hires equaled more profit, job sharks would sell jobs that didn’t exist and sometimes bribe bosses to fire and rehire entire crews of workers.

The IWW strikes back

In September 1909, Flynn arrived in Missoula, 19 years old and a few weeks pregnant. She set up her soapbox on a busy downtown corner and started speaking out against job sharks to workers and passersby. By the end of September, she was joined by other IWW members (or “Wobblies” as they were called). In response, employment agencies and business owners pressured the police department to enforce an ordinance against public speaking.

On September 29, IWW organizer Frank Little was jailed after delivering the first few lines of his speech. He was immediately followed onto the soapbox and onward to jail by Jack Jones (Flynn’s husband), a lumberjack who read the Declaration of Independence, and a civil engineer who saw what was happening and decided to speak up.

Flynn sent messages to regional IWW offices saying, “We need volunteers to go to jail.” IWW members and sympathizers flocked from across the Pacific Northwest—most of them hitching rides on freight trains—to defy the Missoula police. Within days, the city was full of protesters singing songs, shouting slogans and, most importantly, filling the jails.

Mass arrests for free speech

The Wobblies reframed the conflict as a fight for free speech. Their public addresses would excoriate job sharks, employers and capitalism, of course, but would emphasize the infringement of their rights above all. Some speakers repeated the First Amendment over and over until they were arrested, while others read the Bill of Rights.

They would schedule their speeches right before dinner and demand a jury trial in the morning, which delayed their release until well after breakfast. With the jails packed to the brim, the hungry prisoners became a serious drain on the city’s finances.

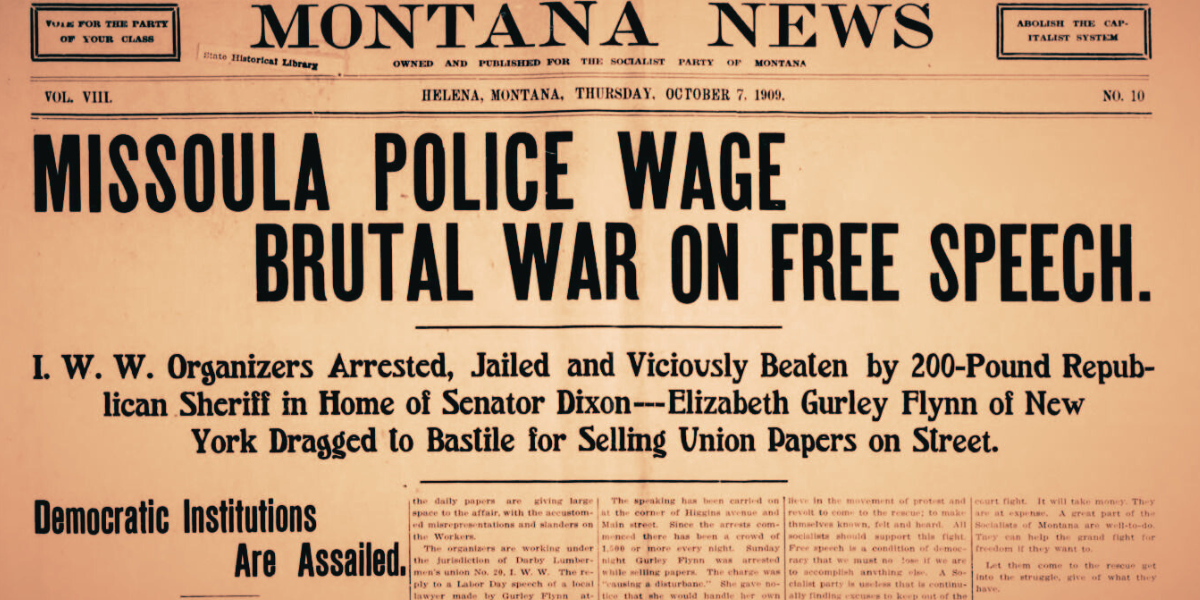

On October 3, Flynn was arrested. Her account of the conditions of the Missoula jail (maliciously placed under the drips of the firehouse stables) was broadcast to IWW locals across the country. Public sentiment began to shift in favour of the IWW, partly out of solidarity and partly out of exasperation.

With their streets and jails filled with disorderly protesters, and with the Western Montana Apple Show only days away, the Missoula city council was forced to concede. All charges were dropped, and the IWW was permitted to speak freely on the streets.

Spokane

Even before the fight broke out in Missoula, the IWW had been building to a similar confrontation almost 300 kilometres west in Spokane, Washington. In December 1908, Spokane’s IWW local started a “Don’t Buy Jobs” campaign to educate and agitate workers around the issue of job sharks.

The city council quickly passed an ordinance outlawing public speaking at the request of the employment agencies. Just like in Missoula, agitators in Spokane used soapboxing and mass arrests to expose the hypocrisy of the city council and the unconstitutionality of the ordinance.

But unlike Missoula, the fight in Spokane did not reach a quick resolution. The IWW had to suspend its campaign over the summer when seasonal workers left the city.

Still, the tactic of mass arrest kept Spokane under constant pressure. When the campaign resumed in October, over 600 protesters were arrested and jailed in one day, with more arriving daily to replace them on the streets.

Flynn arrives

In November, shortly after the fight had concluded in Missoula, Flynn joined the battle. She got up on a soapbox, chained herself to a lamp post and began projecting her ideas to the street.

With her charismatic presence and her clear appeals to the public, she transformed her subsequent arrest and trial into its own kind of soapbox. She used every opportunity to rally the public around the IWW’s basic demands, and she scandalously accused the police of using the jail as a brothel. The IWW’s local paper broadcast Flynn’s accusations to Spokane and beyond despite a crackdown that saw everyone from the editorial board to the newsboys arrested.

By December, public sentiment favoured the Wobblies. Crowds would gather to throw fruits and cigarettes to workers as they were paraded around town. The Western Federation of Miners declared a boycott of all goods coming from Spokane, and Flynn’s trial, which lasted until February, became a national embarrassment for local officials.

On March 3, 1910, the IWW met with city council to discuss a resolution. The agreement was even better than the favourable result in Missoula. Not only was the IWW permitted to soapbox and distribute its newspaper in Spokane, and not only were all charges dropped against the protesters, but the city also committed to reform its employment system and immediately revoked the permits of nineteen job sharks.

Legacy and lessons

After the victories in Missoula and Spokane, Flynn was an important part of the 20th century’s most important movements. Some examples from her illustrious career include leading striking workers during the 1912 Bread and Roses strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, helping coordinate the defence of the Italian-American anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti, developing a close friendship with Claudia Jones, and becoming the first woman to chair the Communist Party USA.

Throughout, she would continue championing free speech as a socialist principle. In 1920, she was one of the founding members of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Although it has since shifted rightward, the ACLU began as a coalition of labour leaders and progressive liberals with the intent of protecting workers’ right to agitate. They expelled her from the executive board in 1939 for being a socialist.

The fights in Missoula and Spokane leave us with important lessons. While civil liberties may be formally recognized, it is up to the working class to guarantee our enjoyment of those freedoms. Free speech rights alone may not save us from oppression, but they do serve as levers to help build class power.

Socialists are committed to the expansion of democratic principles to all parts of society and to the real—not merely formal—freedom of all people. As Flynn proved all her life, when we advocate for civil liberties, we can win the hearts of fellow workers—and win our fights against state repression.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate