“I was deported from the USA because as a Black woman Communist of West Indian descent, I was a thorn in their side in my opposition to Jim Crow racist discrimination against 16 million Black Americans in the United States, in my work for redress of these grievances, for unity of Black and white workers, for women’s rights and my general political activity urging the American people to help by their struggles to change the present foreign and domestic policy of the United States. I was deported and refused an opportunity to complete my American citizenship because I fought for peace, against the huge arms budget which funds should be directed to improving the social needs of the people. I was deported because I urged the prosecution of lynchers rather than prosecution of Communists and other democratic Americans who oppose the lynchers and big financiers and warmongers, the real advocates of force and violence in the USA.”

As Claudia Jones explained in an interview in the mid 1950s, she devoted her life to intertwining struggles against anti-Black racism, sexism, capitalism and imperialism—and for this she was incarcerated, deported, and erased from history. As her biographer, Carole Boyce James explains in Left of Karl Marx: the Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones, the rediscovery of Jones is important for many intersecting struggles:

“The only Black woman among communists tried in the United States, sentenced for crimes against the state, incarcerated, and then deported, Claudia Jones seems to have simply disappeared from major consideration in a range of histories…How could someone who had lived in the United States from the age of eight, who had been so central to Black and communist political organizing throughout the 1930 and 1940s, up to the mid-1950s, simply disappear?…In my view, the deportation of Claudia Jones in a sense effected the deporting of the radical Black female subject from U.S. political consciousness…This rediscovery of Claudia Jones, the individual subject, reinstates a radical Black female intellectual-activist position into a range of African diaspora, left history, and Black feminist debates.”

(While Claudia Jones used “Negro”, the terminology of the day, this has been changed to “Black” in this article).

Black Bolsheviks

Claudia Jones was born on February 21, 1915 in Trinidad (at the time a British colony), and moved with her family to Harlem in 1924. From an early age she experienced how working-class poverty is gendered and racialized:

“Together with my three sisters, our family suffered not only the impoverished lot of working-class native families and its multi-national populace, but early learned the special scourge of indignity stemming from Jim Crow national oppression…My mother had died two years earlier of spinal meningitis suddenly at her machine in a garment shop. The conditions of non-union organization, of that day, of speed up, plus the lot of working women, who are mothers and undoubtedly the weight of immigration to a new land where conditions were far from as promised or anticipated, contributed to her early death at 37…I was later to learn that this lot was not just an individual matter, but that millions of working-class people and Black people suffered this lot under capitalism.”

But the 1920s were also a time of rising resistance to anti-Black racism, which took many forms: the Garvey movement called for separation, the NAACP petitioned for integration, there was cultural resistance through the Harlem Renaissance, and the African Blood Brotherhood organized self-defence. This coincided with a global wave of rebellion in the wake of the Russian Revolution, a working-class revolution that centered the fight against oppression—from decriminalizing homosexuality, to challenging anti-Semitism and the oppression of national minorities, to providing communal kitchens and childcare for women’s liberation. African American socialists were both inspired by this radicalization and contributed to it. After the queer Black poet Claude McKay traveled to Moscow to speak at the Communist International, the Comintern passed its Theses on the Black Question:

“The war, the Russian revolution, and the powerful rebellious movements of Asian and Muslim peoples against imperialism have awakened racial consciousness among millions of Blacks, who have been oppressed and humiliated for centuries not only in Africa but also, and perhaps even more, in the United States…The Black question has become an essential part of the world revolution. The Communist International…views the assistance of our oppressed Black fellow human beings as absolutely necessary for proletarian revolution and the destruction of capitalist power.”

Black socialists and the Comintern’s influence helped orient the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA) to centre struggles against oppression in order to strengthen working-class struggle. When the Depression hit and disproportionately affected Black workers, and especially Black women, the CPUSA organized unemployment councils to demand relief, tenants leagues to fight evictions, and unions—from the Domestic Workers Union in New York, to the Sharecropers’ Union in Alabama—to fight for better wages and conditions. While the American Federation of Labour had reflected the segregation of American society, the Communist union drives helped organize Black workers and give rise to the Congress of Industrial Unions in the 1930s.

The CPUSA also organized against anti-Black violence abroad and at home—from mobilizing Italian and Black communities to march together against Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia, to organizing a multi-racial mass campaign against the legal lynching of 9 Black youth from Scottsboro. As Harry Haywood recalled in his memoir Black Bolshevik, “Through our militant working class policy, we were able to win workers of all nationalities to take up the special demands of Black people embodied in the Scottsboro defence. I’ll never forget how the immigrant workers in the Needle Trades Union would sing ‘Scottsboro Boys Shall Not Die’ in their various Eastern European and Yiddish accents.”

It’s in this context that Claudia Jones joined the CPUSA: “I learned that those who fought most consistently for the interest of the workers, for their trade union organization and social needs were the Communists. My daily experiences as a Black youth in the USA led me to search out political forces that were doing something about these things; political forces who not only fought on a day-to-day basis to alleviate these conditions but who had a perspective as to a radical solution of these conditions.”

She was not the first: Grace Campbell had co-founded the African Blood Brotherhood, Fanny Austin led the Domestic Workers Union, Louise Thompson led the first March on Washington as part of the Scottsboro defence, and Bonita Williams led the Harlem Action Committee against the High Cost of Living. As Jones’ biographer explained, “When Claudia Jones entered the Communist Party there were already examples of very active black communist or leftist women who had visible identities that she could emulate the positions she could advance. In this context, Claudia Jones was not a lone, singular figure, or unusual. What marks her instead is that she became both an organizer and a leading theoretician.”

Intersectional socialism

Forty years before the term “intersectionality” was coined, Claudia Jones called for centering Black women workers—whose experience could not be reduced to either racism or sexism: “Black women—as workers, as Blacks, and as women—are the most oppressed stratum of the whole population… The super-exploitation of the Black woman workers is thus revealed not only in that she receives as woman, less than equal pay for equal work with men, but in that the majority of Black women get less than half the pay of white women.”

This was not just a question of economics but also ideology. The post-WWII conservative backlash called for women to return to the home, but as she pointed out this sexism was racialized, especially for domestic workers:

“The bourgeois ideologists have not failed, of course, to develop a special ideological offensive aimed at degrading Black women…They cannot, however, with equanimity or credibility, speak of the Black woman’s ‘place’ as in the home; for Black women are in other peoples’ kitchens…The whole intent of a host of articles, books, etc, has been to obscure the main responsibility for the oppression of Black women by spreading the rotten bourgeois notion about a ‘battle of the sexes’ and ‘ignoring’ the fight of both Black men and women—the whole Black people—against their common oppressors, the white ruling class.”

What made her intersectionality socialist was that Claudia Jones differentiated between the ruling class that generated and that benefited from oppression, and the working class that internalized oppressive ideas and behaviors despite their class interests. This meant organizing a working-class strategy of fighting oppression, as she summarized in her 1949 essay “We Seek Full Equality for Women,”: “The triply-oppressed status of the Black woman is a barometer of the status of all women, and that the fight for the full economic, political and social equality of the Black woman is in the vital self-interest of white workers, in the vital interest of the fight to realize equality for all women.”

This didn’t mean subordination issues of oppression to the class struggle, but of challenging the women’s movement, trade union movement and her own party to fight every manifestation of sexism and anti-Black racism in order to raise the level of struggle:

“We can accelerate the militancy of Black women to the degree with which we demonstrate that the economic, political, and social demands of Black women are not just ordinary demands, but special demands, flowing from special discrimination facing Black women as women, as workers and as Blacks. It means first, to unfold the struggle for jobs, to organize the unorganized Black women workers in hundreds of open-shop factories and to win these job campaigns. It means overcoming our failure to organize the domestic workers…And it means that a struggle for social equality for Black women must be boldly fought for in every sphere of relations between men and women so that the open door of Party membership doesn’t become a revolving door because of our failure to conduct this struggle.”

Drawing on the militant history of Black women, from fighting slavery to organizing strikes in the 1930s, Claudia Jones theorized the intersection of Black liberation, women’s liberation and socialist revolution:

“Only to the extent that we fight all chauvinist expressions and actions as regards the Black people and the fight for full equality of the Black people, can women as a whole advance their struggle for equal rights. For the progressive women’s movement, the Black woman, who combines in her status the worker, the Black and the woman, is the vital link to this heightened political consciousness. To the extent, further, that the cause of the Black woman worker is promoted, she will be enabled to take her rightful place in the Black-proletarian leadership of the national liberation movement and, by her active participation contribute to the entire American working class, whose historic mission is the achievement of a Socialist America—the final and full guarantee of woman’s emancipation.”

Dream deferred

Tragically, this vision was undermined by Stalinism and McCarthyism. While the Russian revolution had inspired Communist Parties around the world, the counter-revolution undermined them. During WWII the CPUSA subordinated civil rights, women’s rights and workers struggles to the war drive. Trinidadian Trotskyist CLR James explained the results:

“The line changed from one that at least attempted to be revolutionary to one which is today openly tied to American imperialism and the Roosevelt war machine. The result was immediate and unmistakable: of their 2000 Black members in New York State, the CP has lost over 80% and the same thing happened all over the country.” Jones followed the party line during the war, but was more critical afterwards.

Then came the McCarthyist backlash against the left, which especially impacted Black socialists—deporting the theoretician WEB DuBois, the union organizer Ferdinand Smith, the Trotskyist James and the Communist Jones. She joined the Communist Party of Great Britain, but it had all the problems of Stalinized parties without any of the legacy of Black socialists from the CPUSA, and was more interested in a “British road to socialism” than anti-colonialism. So Jones organized on her own.

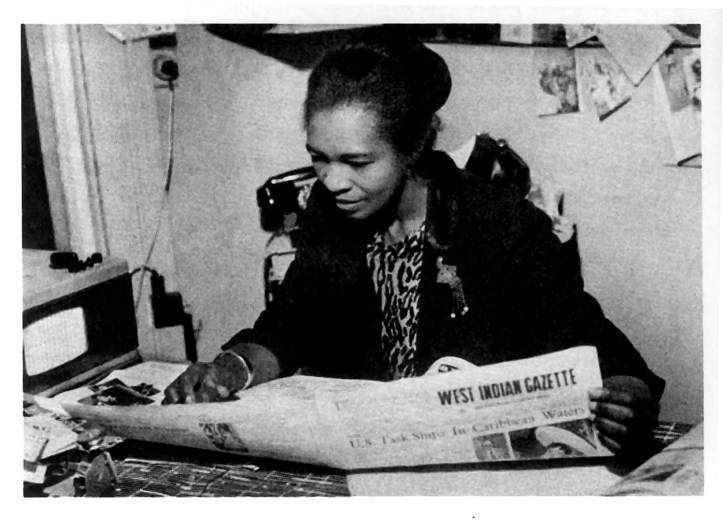

Building on her decades of journalism fusing Black and working-class struggles, she launched and edited Britain’s first major Black newspaper. The West Indian Gazette and Afro-Asian-Caribbean News built solidarity with anti-colonial struggles abroad and fought against anti-migrant and anti-Black racism at home:

“Faced with a radical movement of the masses against their rule, they seek to split and divert this anger onto a false ‘enemy’. Added to the second-class citizenship foisted by such a measure, West Indians and other Afro-Asians are confronted in their daily lives with many social and economic problems.”

Drawing on CPUSA experience with the Harlem Renaissance and the Scottsboro campaign, she launched the first Caribbean Carnival as a protest against anti-Black violence. As new struggles were emerging she organized a parallel March on Washington in London, and a British boycott campaign against South African apartheid. But years of ill health from growing up in a racist, sexist, capitalist society, and of being incarcerated and deported, took their toll. She died in 1964 at the early age of 49, and is buried next to Karl Marx.

Despite the deportation of Claudia Jones, the legacy of Black socialists continued. As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor explained in From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation, “far from being marginal to the struggles of Black people, socialists have always been at the centre of those movements—from the struggle to save the Scottsboro Boys in the 1930s, to Bayard Rustin’s role in organizing the 1963 March on Washington, to the Black Panther Party’s organizing against police brutality.”

Now there are new movements like Black Lives Matter, a renewed interest in socialist politics, and a rediscovery of activists that embody their intersection. As Angela Davis explained on the centenary of the American Communist Party, “After persistent attempts to obscure the Party’s historical role and that of organizations like the Southern Negro Youth Congress in organizing industrial workers, sharecroppers and tenant farmers in the South, it is becoming increasingly clear that this work helped create a political terrain on which struggles against Jim Crow segregation would eventually thrive. Young scholars who have extricated themselves from the lingering influences of McCarthyism, are now uncovering the invaluable contributions of Communists. Having visited Claudia Jones’ grave—immediately adjacent to the grave of Karl Marx—in Highgate Cemetery, I am especially happy that her ideas have now been incorporated into many histories of US Black feminism.”

Pick up a copy of “Left of Karl Marx: the Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones” from A Different Booklist

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate