Gig workers in Ontario might be experiencing a bit of whiplash.

On Monday, February 28, Gig Workers United, a union that represents app-based delivery workers, announced that one of its members had received a successful decision from the Ministry of Labour regarding the employment status of an UberEats delivery driver. The decision, rendered by an Employment Standards Officer in response to a complaint filed by delivery driver Saurabh Sharma, found that Sharma was an employee of Uber. This means that he is entitled to all the protections listed in the Employment Standards Act (ESA), including minimum wage, vacation pay, overtime, and termination pay.

The decision only applies to Mr. Sharma and Uber still has a right to file an application for review to the Ontario Labour Relations Board. Nevertheless, this is a huge win for gig workers in Ontario. It vindicates gig workers who have long been maintaining that they deserve these rights, despite government inaction and a systemic lack of enforcement.

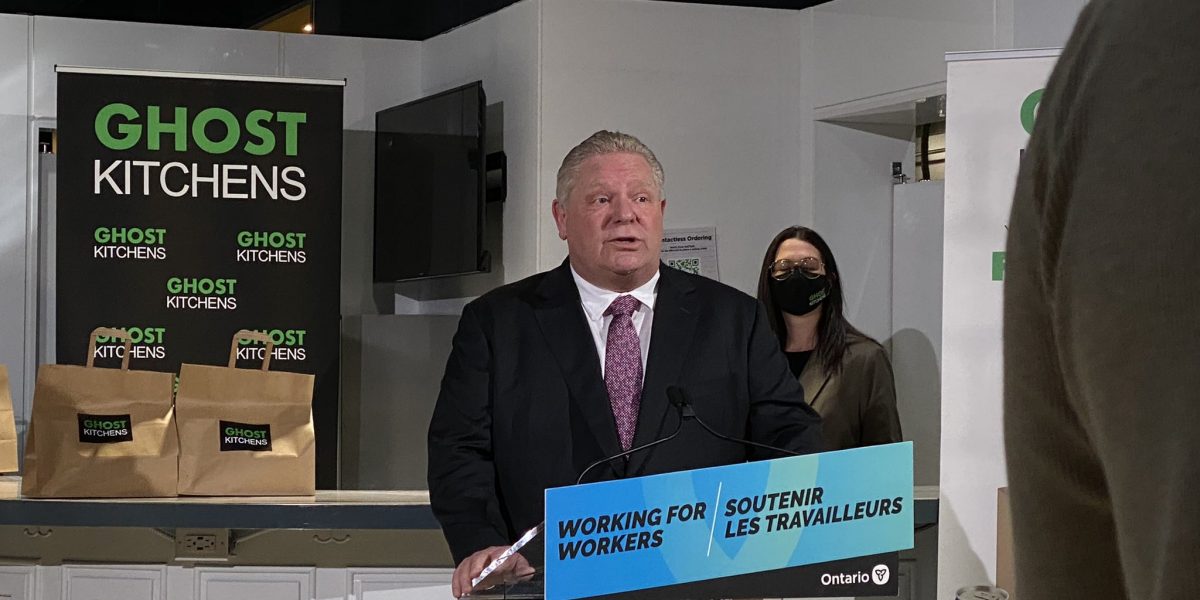

Within hours of the release of Gig Workers United’s press release, however, Labour Minister Monte McNaughton introduced Bill 88, Working for Workers Act, 2022, a Bill which purports to create rights and protections for gig workers via the Digital Platform Workers’ Rights Act, 2022 but actually provides them with lesser entitlements than they are already entitled to under the law as employees.

Bill 88: The other shoe drops

Under the Employment Standards Act, 2000 a worker is entitled to minimum wage (currently $15/hr) from the moment they clock in to the moment they clock out (not including unpaid breaks). Bill 88 would create a separate minimum wage entitlement for app-based delivery workers that only applies to time spent actively engaged in a delivery or ride. Though it is still somewhat ambiguous how the proposed legislation will work in practice, the Bill’s language likely means that delivery workers will only be paid while actively completing an order, not while they are driving to and from customers or waiting for a pick up.

Gig Workers United President Jennifer Scott likens the proposal to only paying a cashier for the time spent actively ringing out a customer. According to a 2019 vehicle for hire impact study conducted in Toronto, drivers spend approximately 40 percent of their time waiting for clients. When factoring in the actual amount of time that gig workers have to spend logged into an app, Bill 88 delivers an hourly wage that is closer to $9.00/hr. When factoring in the cost of gas and mileage, which drivers shoulder themselves, the rate is even lower.

Other rights which the Bill separately creates for gig workers, such as protection from reprisals and unlawful dismissal without notice, are already owed to them under the Employment Standards Act. The Bill is silent on other ESA entitlements, such as vacation, overtime, and public holidays, and severance/termination pay.

Not what gig workers are asking for

Treating employees as independent contractors to reduce labour costs – a practice known as employee misclassification – is a longstanding employer practice aimed at reducing labour costs. It is particularly prevalent in certain industries, including trucking, cleaning services, and construction. The novelty of platform-based apps is not in the services they provide but the scale on which they are able to misclassify workers.

Uber, DoorDash, and other digital app-based platform companies try to claim that they are not employing drivers, but merely serve to connect them to customers. They downplay the extent to which they control the relationship between delivery workers and customers by setting prices, controlling access to customers, establishing rules for engagement, and monitoring employee/customer interactions. This allows them to forgo honouring any of the rights and entitlements they would owe their workers if those workers were legitimately recognized as employees.

In jurisdictions around the world, from the UK, to Spain, to New Zealand, gig workers have been pushing back against Uber’s false narrative of flexibility through union organizing campaigns, litigation, and protests. Uber, Lyft, and other app-based companies can see which way the wind is blowing. While continuing to union-bust and fight their workers in court, these companies have also gone on the offensive, lobbying lawmakers to create special rules for gig workers that work in their favour.

This strategy was first tested in California. In 2019, legislation known as AB5 was passed which adopted a more rational approach to the distinction between employees and independent contractors. Under the adopted “ABC” test, a worker is considered an employee if, among other things, the tasks they perform are part of the employer’s regular business, and if the employer exerts control over how an employee’s tasks are performed. Under this test, delivery gig workers would most definitely be employees. In response, Uber, Lyft, and other gig employers aggressively lobbied for legislation known as Proposition 22 to legally deem their workers as independent contractors, while giving them some lesser entitlements. After Uber and Lyft spent more than $224 million dollars promoting the law, Proposition 22 passed. Similar employer-friendly legislation has recently been proposed in Massachusetts and Washington State.

NDP MPP Peggy Sattler proposed legislation similar to AB5 in Ontario. Not unsurprisingly, the Conservatives voted against it.

Ford’s employer friendly agenda

Uber’s lobbyist have also found sympathetic ears among Canada’s federal and provincial Conservatives. In March 2021, the Proposition 22 strategy was exported to Ontario when Uber released a proposal called “Flexible Work+”, asking lawmakers to consider reforms specific to delivery gig workers.

Instead of conceding to workers’ actual demands, the Flexible Work+ model proposes half-measure versions of the benefits that gig workers would already be entitled to as employees. Instead of a guaranteed minimum wage for all hours worked, Uber offers minimum wage but only for “engaged” time. Where employees would be entitled to employer matching contributions to the Canadian Pension Plan and Employment Insurance – including unemployment, sick, and pregnancy/parental benefits – Uber proposes a portable benefit package that would likely payout meagre sums, and which many delivery gig workers aren’t likely to qualify for. Instead of the right to unionize, access WSIB, file individual complaints for minimum standards or health and safety violations, Uber proposes private arbitration with representation not of the worker’s choosing.

Uber’s strategy is clear, it wants to offer the crumbs of reform to forestall giving the full rights and benefits gig workers are actually entitled to.

Soon after Uber started pitching its Flexible Work+ program in Canada, Ontario initiated the Ontario Workforce Recovery Advisory Committee (OWRAC). One of the primary focuses of the Committee was to “ensure Ontario’s technology platform workers benefit from flexibility, control, and security.” Initially, the entire consultation process was supposed to take less than a month. Worker advocates were quick to point out that there were no union or worker representatives appointed to the OWRAC advisory committee, nor did workers have the opportunity to share their views with the committee via oral hearings.

Consider for comparison the Changing Workplace Review, which was the last employment and labour law review process initiated by the Wynne government in Ontario and took over two years to complete. A two-person advisory committee heard from over 200 stakeholders, received over 300 written submissions, released an interim report to receive further public feedback, before finally publishing a final report containing 173 detailed recommendations. In contrast to that process, the OWRAC struck many worker advocates as a rubber stamping exercise orchestrated by Ford’s government to pave the way for the types of changes that Uber had been advocating for.

Despite being a deeply flawed and rushed process, gig workers and their allies did their best to ensure that the OWRAC Committee understood what gig workers want, including full employment rights with no carve-outs, payment for all hours worked, full and equal access to benefits like CPP and EI, and recognition of the right to unionize.

The OWRAC committee published recommendations in November 2021, including the creation of a separate “dependent contractor” category for gig workers that exists somewhere between an independent contractor and an employee. Thanks to significant advocacy from gig workers and their allies, Bill 88 is not a wholesale adoption of Uber’s proposals or the OWRAC recommendations, both of which may have carved gig workers out of even more entitlements. But by creating a separate minimum wage for delivery gig workers that only applies for “engaged time”, Bill 88 does adopt one of the most significant planks of Uber’s proposal.

Ford’s trojan horse

With an election coming up in June, Ford and his cabinet are yet again talking a big game about helping the little guy. But Bill 88 offers gig workers peanuts while blocking them from the same minimum wage that applies to almost all other workers in Ontario.

Ford has spent the last two years paying lip service to frontline workers while at the same time voting repeatedly to deny workers paid sick days, capping public workers’ salaries at below-inflation levels, and withholding federal money for childcare. Bill 88 is another one of Ford’s trojan horses. Lest anyone be fooled by the Orwellian title of Bill 88, this government is in no way “Working for Workers.” At best, Bill 88 duplicates some of gig workers existing entitlements. At worst, it legitimises a form of wage theft that is the cornerstone of the app-based platform companies’ business model.

Moreover, the Bill may open the door to further precarity in other sectors. As written, Bill 88 only applies to “digital platform workers who provide ride-share, delivery, or courier services”, but its application can be expanded to different types of workers later via regulation. Given the ever increasing number of industries shifting toward just-in-time labour models (what some have called the “Uberization” of everything), Bill 88 could potentially incentivize further misclassification, and encourages employers to switch to labour models that are inherently more precarious.

If we want to seriously address workers’ rights in the gig economy, the first thing we need to do is ensure workers have access to the full rights and benefits that are afforded to other workers under the Employment Standards Act. Anything short of this leaves gig workers behind and threatens to erode employment standards for all workers.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate