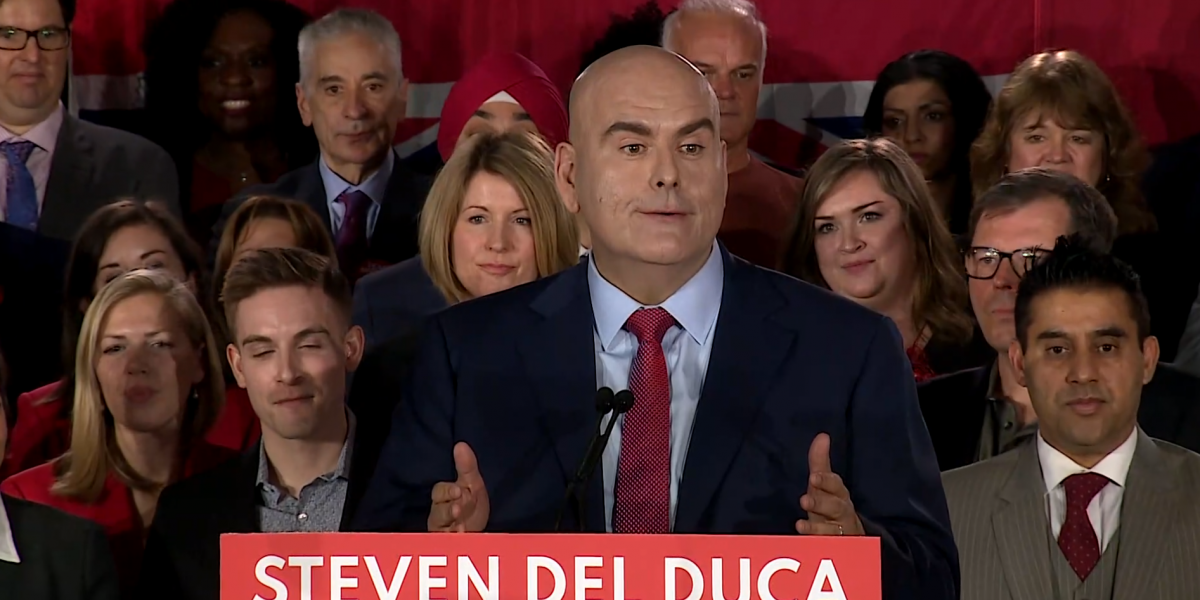

Hoping to gain traction in the lead up to the June election, last week Ontario’s Liberal Party leader Steven Del Duca took off his glasses and announced a new bold vision for Ontario’s workers: a regional minimum wage model.

Del Duca’s plan is to raise the current minimum wage from $15 to $16 an hour in 2023 and then introduce “a regionally adjusted living wage”. This would be done by engaging in a consultative process to set up a regional living wage structure. While this may sound like progress for Ontario’s workers, this would be a huge boon to employers and weaken efforts to create a strong employment standards floor for all workers.

Del Duca’s announcement is not a worked out plan, it is a fuzzy election promise that threatens to open the door to further fracture employment standards in Ontario and accelerate the race to the bottom for workers.

The decent work movement is calling for raising the minimum wage to $20 and tying it to inflation. The most obvious issue with Del Duca’s plan is it goes against this demand, and will leave workers much further behind. Roughly two million Ontario workers make less than $20 an hour. According to the Living Wage Network’s most recent regional calculations only two regions in Ontario, Toronto and Halton, have a living wage above $20 an hour. Workers in Ottawa, Peel, Hamilton, Kingston, Niagara, Sudbury and every other region would be making less than $20 an hour, in some cases significantly less. Under the Liberal plan the total amount of wages going into workers’ pockets would be significantly less than simply raising the minimum wage to $20 an hour.

But this is far from the only problem with the Liberals regional living wage proposal. To understand why this would truly be a step back for workers, it is important to grasp what the living wage is.

Living wage: theory vs practice

For most people the rhetoric of a “living wage” is used as a way of describing a “fair” wage compensation in relation to their living standards. Thus, if people are asked if they support a living or livable wage most would be supportive. But in terms of policy the living wage is quite different.

The modern living wage movement can be traced back to the efforts of trade unionists and anti-poverty activists in the 1990s to pressure cities in the United States to adopt living wage policies for municipal workers and contractors. While initially successful in cities like Baltimore, Boston, and Milwaukee, the movement failed to achieve major gains. Legislation passed at the municipal and state level only ever covered a small fraction of public sector workers. By the mid 2000s the campaign and the labour movement’s involvement fizzled. In Canada, Living Wage Canada and its local groups are the main force pushing this policy. It focuses on voluntary and unenforceable agreements with local business (most of which are NGOs). As a movement it has been largely ineffective–not because of a lack of implementation but because of inherent problems in the living wage model.

The living wage calculation is done by academics based on an “ideal family type” (two healthy adults both working 35 hours a week with two children aged seven and three) meeting basic needs in a given region. The details of the living wage calculation’s methodology are laid out in the Canadian Living Wage Framework: National Methodology for Calculating the Living Wage in Your Community. The framework sets the living wage based on what the two wage earners in this family of four need to earn per hour to meet basic expenses. This factors in costs of housing, transportation, child care, food, as well as tax credits.

The problems become readily apparent when you understand that the living wage is means tested against social spending. In other words, what moves the living wage up and down in a given region are factors such as rent, food prices, childcare, tax credits and transit. So raising the spending on social programs, which lowers the cost of childcare or transit, results in the lowering of the living wage. In this model of wage calculation, it is not employers profits that matter, it is social spending.

While the living wage can certainly rise in times of high inflation, it can and has been lowered repeatedly to factor in things like child tax credits from the government (this happened in 2017 and 2019). Wages should not be means tested to social spending. If social movements are able to win lower public transport costs or lower childcare costs, this gain should not be cancelled out through reductions in the living wage.

The recent childcare agreements look set to significantly lower the cost of childcare across Ontario over the next several years. This will dramatically lower the living wage calculations in communities across the province (and country). If the rise in inflation tapers off in the latter half of 2022 and into 2023 as many expect, there could be a significant reduction in the living wage. Any reduction in post-secondary costs could also lower the living wage as well.

The problems with the regional living wage model don’t just rest on its means tested calculation of wages. The regional calculation aspect of the model is just as problematic for workers. While it is good for workers to understand local variance in cost of living and consumer prices, it is a big step backwards to begin to carve up a section of the Employment Standards Act based on regions.

Dividing workers, empowering bosses

A regional living wage calculation will further fracture the wage floor, creating more divisions between workers while giving employers greater latitude to put downward pressure on wages. It is totally unclear how the Liberal propose to implement a regional living wage model. What happens when workers live in one region and work in another, as is often the case, especially in Southern Ontario. If a worker lived in Toronto and worked in Barrie, would they be paid the regional living wage in Barrie or Toronto? If it is the former, how would this reflect their cost of living? If the latter, it means workers in the same workplace would be getting paid differently for doing the same job. Any way you slice it, the implementation of a regional living wage as a minimum wage would nonsensical: it would mean having workers work for the same company, doing the same job, making different wages.

This would be a recipe to further divide workers and make forging solidarity that much more difficult. It also cuts against the basic premise of equal pay for equal work, something the Liberals say they support. How could one legislate equal for equal work while constructing a regional wage minimum wage model that would exactly the opposite? There is also a clear racial justice argument against a regional living wage model. Why should workers who live in downtown Toronto make $3 more an hour than workers living in Peel. The structures of racism, through the housing market and labour market, shape who lives where in our cities and province. The regional living wage model would not just fail to rectify this, it would reinforce and accentuate existing inequities in the labour market.

Fracturing the minimum wage floor means opening the door further for employers to threaten to move their operations from one region to a lower wage region. This would disempower workers from fighting for higher wages, stronger protections and benefits. If workers were paid based on their postal code, it could mean fomenting divisions with workplaces. A regional living wage model would also make it harder to build a broader class unity to fight for increased wages as they would be divided regionally. Employers and the government would point to the existing living wage model, and use that powerful rhetoric to argue against furth wage increases. Rather than involving workers in struggle for higher wages, this model lends itself to academics debating about the minutiae about how living wage models should be constructed.

On top of that, the logic of opening the ESA to a regionally based metric is dangerous. Should vacation pay be calculated differently in different regions? Do workers in Hamilton deserve fewer legislated paid sick days than workers in Toronto? Should overtime rules be constructed differently in Ottawa than in Thunder Bay? Paid sick days, vacation pay, overtime rules are all costs. If wages are regionally calculated, what is to stop employers from demanding other aspects of the ESA shouldn’t be regionally differentiated?

Building unity through stronger employment standards

The history of the labour movement is a fight for strong and universal rights and benefits for all workers. It is about raising the floor of employment standards to give workers the leverage to fight for more–not introducing more differentiations, exemptions, loopholes and carve outs.

For instance, our Unemployment Insurance program was at its strongest after the passage of the Unemployment Insurance Act of 1971 which provided near universal coverage (roughly 96% of workers were covered). When the Trudeau government looked to curb the program they introduced a Variable Entrance Requirement (VER) in 1977 that determined eligibility and length of benefit based on a region’s unemployment rate. The EI system has been attacked by nearly every government since, and one of the biggest mechanisms to curb people’s access to the benefit has been through the VER. Trudeau Jr.s temporary removal of the VER in 2020/21 helped to increase access and make the program more accessible for all.

Del Duca’s proposal for a regional living wage model may have some rhetorical appeal for workers struggling to make ends meet. But in practice, it would put far less money in workers pockets than a $20 minimum wage–which is why the Liberals are proposing it. For years, previous Ontario Liberal governments froze the minimum wage. By building unity and fighting for universal standards, the decent work movement won a wage increase from $11.40 to $14 in 2018. This directly benefited workers earning less than $14 and put upward pressure on the wages of those earning more–across every region. The raise in the minimum wage benefited millions of workers, which was far more effective than any living wage campaign and was not counterposed to social programs. The Ford government again froze the wage, but the movement was able to force him to reverse course and raise the minimum wage to $15.

Now that workers are mobilizing for a $20 minimum wage, the Liberals are paying lip service to the movement while seeking to restrain and divide it. But we shouldn’t embrace a vague promise for higher wages that in practice will trade off gains of social programs for wages, divide rather than unite workers, and allow employers to exploit a more fractured ESA. We need to keep building the decent work movement, to fight for a $20 minimum wage in every region and stronger employment standards for all.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate