In the Spring of 2023, Scott Moe was interviewed about Saskatchewan’s current levels of homelessness and unemployment, and the programs in place to address these issues. In a moment of biting irony and political blindness, the Premier compared Saskatchewan residents’ standard of living to that of King Louis XIV of France. Moe is quoted as saying, “we’re very fortunate in most nations around the world simply because we have enough to eat.” He said King Louis XIV “lacked many things we take for granted that we’re accustomed to,” and that he would be “quite shocked” at our abundance. Perhaps unwilling to admit the failures of his own Party’s approach to the province’s woes, or perhaps unaware of the grandeur of King Louis’s life; either way, Moe’s comments are out of touch with the utter lack of abundance facing working class people in Saskatchewan.

In 2022, French President Emmanuel Macron made headlines by forecasting the “end of abundance.” Facing a mounting economic crisis, spurned not only by the COVID-19 pandemic but also by the severing of ties between the European Union and Russia, France and the rest of Europe have been on a downward economic turn. While the predictions state that the French economy is set for only a mild recession, it is the working class that will be hit the hardest. Macron has been described as non-negotiably “pro-business.” French wealth inequality has led thousands of French citizens to strike for higher pay this year. The end of abundance in France has already been given form in Macron’s bid to raise the national pension age. But for many French workers, abundance is not something that is only now leaving, but something that was never quite tangible.

While our current era of global crises is business-as-usual for many poor and working-class French citizens, do we have a relative state of abundance here on the Prairies? Let us take a look at the state of our economic and social situation.

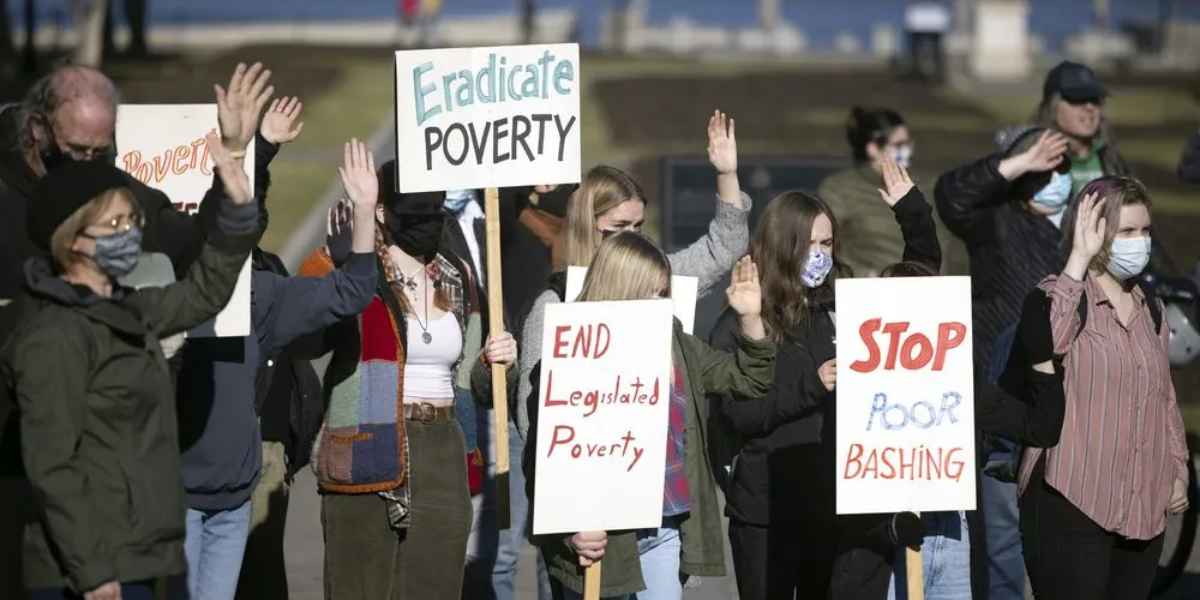

Homelessness reaches record levels in Saskatchewan

In 2009, a Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives report found that Saskatchewan ranked highest among all the provinces in rates of homelessness. According to the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, homelessness describes “the situation of an individual, family or community without stable, safe, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect, means and ability of acquiring it.” Studying homelessness can be very difficult, resulting in imperfect data. Even with new methodologies to estimate the scope of homelessness, most researchers and organizers point out that “the count is always an underestimate.” Despite this, a new count of Saskatoon’s homeless “found a record 550 people living on the streets.” The issue of homelessness in Saskatchewan has only been worsened by the recent COVID-19 pandemic and the inflationary crisis. Many of those who qualify as “homeless” by certain definitions are those who are living precariously: unsure of whether or not they will be able to afford rent, clothing, food, and other necessities. At any moment, these people might find themselves totally unhoused, especially as prices soar all over the province.

Homelessness is not exclusively a financial issue, but also a racial issue. One estimate found that 90 percent of Saskatchewan’s homeless population is Indigenous. Another estimate places the provincial figure at 82 percent. Statistics Canada writes, “although a minority of Canadians experience homelessness at a certain point in their life, some groups are at an elevated risk, including sexual minorities, Indigenous people and Black women.” Saskatchewan’s rate of Indigenous homelessness places it well above the countrywide estimate of about 30 percent. For the province’s homeless, this is certainly no age of abundance, especially compared to King Louis XIV.

How has Scott Moe responded to the epidemic of homelessness in our supposed age of abundance? According to Saskatchewan’s mayors, the provincial government is not doing enough. As many Canadians could guess, social services and safety nets are too few and too inconsequential to combat the numbers and depth of the homelessness and poverty crisis.

The Mayor of Lloydminster was quoted as saying that impoverished people “received far less than the actual cost of living in Saskatchewan [from social services payouts], making it nearly impossible for them to begin making their way back to stable living and joining the workforce.”

Scott Moe’s Social Services Minister, Gene Makowsky, was able only to pander to “pragmatic” inclinations, saying that homelessness is a “complex issue.” But as one organizer said, “you can’t just pay lip service to it. You have to actually do something about it.” It seems that all Moe and his government are concerned about is the rhetorical issue of homelessness, rather than its reality. As they refuse to fund services or fill empty housing units, people will continue suffering in this province of abundance.

A related crisis facing Saskatchewan is housing prices. While not nearly as bad as the Vancouver and Toronto markets, Saskatoon and Regina homes average about $380,100 and $316,100, respectively. The past five years have seen an average increase of about $16,500 on Saskatchewan homes. While housing prices continue to rise, unchecked by either the federal or provincial governments, Saskatchewan citizens are forced to bear the burden of the added costs of living in our latest inflationary crisis.

Saskatchewan hit particularly hard by cost of living crisis

While struggling to pay rents and mortgages, people are also grappling with increased fuel, grocery, and power costs. Some have even cut out essential foods such as fresh fruit in order to save money. Saskatchewan had the third highest rate of inflation among all the Canadian provinces this past year.

Along with the crisis of housing prices comes increased utility and general living costs for Saskatchewan residents. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) measures the average utility, food, shelter, clothing, retail, and other costs for Canadians over time. In June 2020, Saskatchewan’s CPI was 141.2, whereas it stood at 160.4 in June of this year: an increase of 19.2 points. Even those who are not living in precarity are struggling to keep up with increasing prices in every area of normal life. A recent survey found that nearly half of Canadians in Manitoba and Saskatchewan regret their current levels of debt.

In light of the numerous crises facing Saskatchewan residents, one wonders how Scott Moe thought it fitting to call the province a land of abundance. Is he really so disconnected that he is unaware of these issues? This does not seem to be the case, as his government is keen on paying lip service to the province’s problems, while failing to provide solutions. It is more likely that Premier Moe was lauding himself for the illusory achievements of his leadership. But while his Saskatchewan may be one of plenty, many of us are living in an era of scarcity.

As the cost of living continues to rise, and more people are placed into precarity or homelessness despite our supposed abundance, we should remember that Saskatchewan (and Canada) has abundance enough to guarantee every resident a substantial quality of life, guaranteed work, and socialized services. The problem we face now is due to the existing allocation of our abundant resources. While the rich flourish and continue accumulating wealth, the working class (Indigenous peoples most of all) continues to suffer. Our question should not be how to produce abundance in Saskatchewan, but how to attain for the working class what already exists for the bourgeoisie. This will come about through class struggle.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate