Tens of millions of Brazilian progressives spent the three days before the October 2 general elections in an exalted state of semi-nirvana. Two massive polls (with over 12,000 respondents each) released on Thursday, September 29 and Saturday, October 1 showed ex-President Lula of the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT) with a distinct chance of winning in the first round and substantial advantages for left-wing candidates in races for governor, the Federal Congress and State Assemblies around the country. Left triumphalism reigned on social media and not a few went to the voting booths on Sunday with an absolute certainty that the four-year-old nightmare of neofascist Bolsonarismo was soon coming to an end.

We were in for a rude awakening at about 8 p.m. on Sunday when the final results came in. Lula received 48.43% and Jair Bolsonaro 43.20%, forcing a second round of presidential elections on October 30. In two months of weekly polling during the campaign, Bolsonaro had never garnered more than 37% and Lula had stabilized in the last days before the elections at about 50%. Lula was expected to win handily in the three largest states, but only took one. The polls were thus somewhat off, but not hugely so.

Polls erred, again

Where the polls erred immensely were the projections for Governors, the Federal Congress, and State Assemblies. Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party (PL) and numerous small, allied parties made significant gains. Gubernatorial candidates aligned with Bolsonaro were elected or re-elected in seven states while he is supported by another eight candidates in the second-round elections. Allies of Lula won in four states in his steadfast base in the Northeast of the country and counts on the support of another six candidates in the runoffs. Bolsonaro may well win the support of more than half the country’s 27 governors by the end of the elections.

The biggest surprise was in the largest state, São Paulo. Polls consistently showed Fernando Haddad of the PT with a substantial lead against Bolsonaro’s hand-picked candidate, the ex-Minister of Infrastructure, Tarcísio de Freitas, a native of Rio who was parachuted into the state to expand Bolsonaro’s influence. Yet Freitas ended up with 42.32% and Haddad with 35.70%. In Rio de Janeiro, the second largest state, Bolsonaro’s candidate, Claudio Castro, mired in massive corruption scandals, won handily against the left-wing candidate, Marcelo Freixo, with 60% of the votes. In Minas Gerais, the one large state where Lula won the majority of votes for president, the closet Bolsonaro supporter, Romeu Zema, prevailed with 56% in his reelection bid.

Bolsonaristas swept the lower house of Congress with the PL winning 99 seats. With allied parties, they will control more than half the seats as in the Senate, where the PL won 13 of the 27 seats up for grabs.

Nothing illustrates more the far-right onslaught than the fact that four controversial ex-ministers of the Bolsonaro government won decisively in Congressional races. The former Health Minister, Eduardo Pazuello, responsible for the criminal mismanagement of the pandemic in the country with the second-highest number of deaths in the world from COVID, was the second-most voted Federal Deputy in Rio de Janeiro. Ricardo Salles, the ex-Environment Minister, who gutted environmental regulations and cozied up to illegal mining and timber companies to facilitate the deforestation of more than a million hectares of land in the Amazon in the past year, was the third-most voted Federal Deputy in São Paulo with over 640,000 votes. Once again defying the polls, the ex-Minister of Science and Technology, the astronaut, Marcos Pontes, who destroyed his Ministry with drastic cutbacks, finished first in the race for Senate in São Paulo. And the deranged evangelical and ex-Minister of the Family and Human Rights, Damares Alves, who grossly disrespected human rights and denied abortions to girls who were raped and impregnated, won the Senate race in the Federal District.

There were small victories for the left. The Party of Socialism and Liberty (PSOL), who split from the PT in 2003, increased its numbers of Federal Deputies from eight to twelve, including two indigenous women and a Black trans woman. Guilherme Boulos of PSOL and leader of the Homeless Workers’ Movement won more than a million votes for Federal Deputy in São Paulo. Even the PT increased its numbers in the Congress and scored well in the Legislative Assembly of São Paulo along with PSOL.

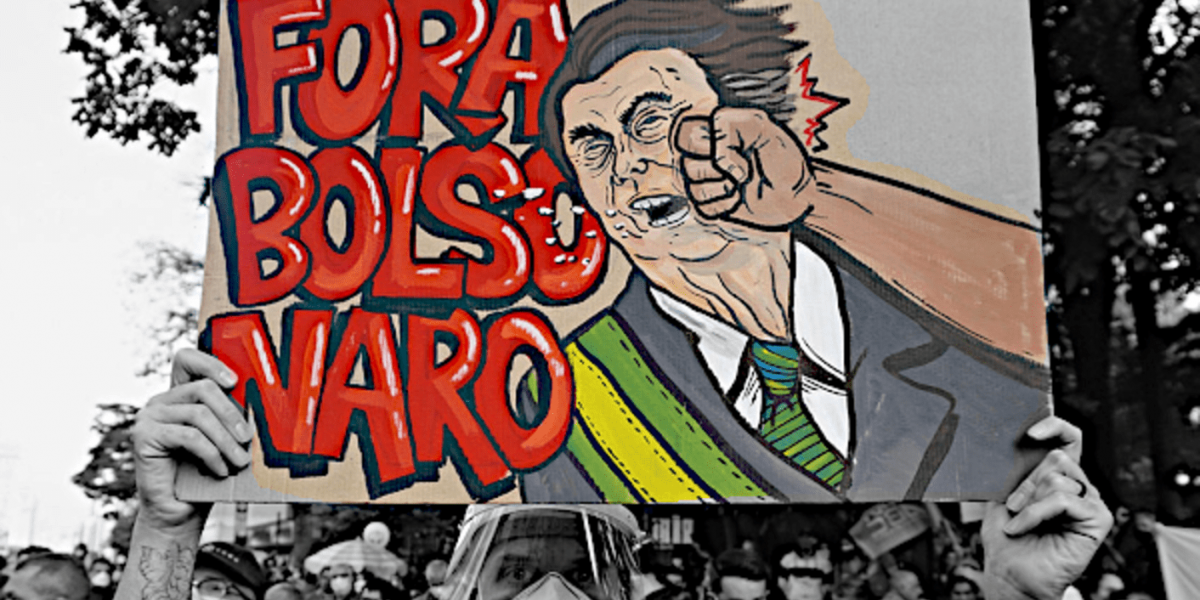

But all these pale in comparison to the right-wing Bolsonaro offensive. Even with the unmitigated disaster of the Bolsonaro government—double-digit inflation and unemployment, 30 million suffering from hunger, drastic cutbacks to the fledging Brazilian welfare state and labour and pension rights, the inhumane handling of the pandemic, constant attacks against oppressed people, and veiled threats of a coup—how do we explain his staying power and why the polls were so wrong?

Ideology vs. mobilization

A fuller analysis will only emerge in the next few months, but two factors stand out: the depth of far-right, even neofascist, ideology among the Brazilian population and the almost exclusive left focus on parliamentary elections and top-down, passive political mobilizations.

The fact is that the polls were incapable of gauging the penetration of right-wing ideology among a considerable proportion of Brazilians, something also witnessed in other contexts such as Trump in 2016 and Orban in Hungary earlier this year. Pollsters and the left have underestimated how the simple, authoritarian solutions offered by Bolsonarismo, however false, have struck a deep chord with many people, especially the white, male lower-middle class, but not exclusively. Resentful of recent gains by workers, women, Blacks, and the LGBT community, they have projected hate toward the oppressed, betting on economic and social betterment through top-down favours of the elite.

As several innovative ethnographers of the far right have shown, this has resulted in unconditional support for Bolsonaro by at least one-third of the population who have enthusiastically embraced his chief campaign slogan “God, Fatherland, Family and Freedom,” taken literally right out of the playbooks of Italian fascism, German Nazism, and Brazilian Integralism, a homegrown fascist movement in the 1930s. A central part of this ideology includes a visceral hatred of the PT and left—fed by fake news and outright lies—actively cultivated since the parliamentary coup against PT President Dilma in 2016. It’s high time to revisit Adorno’s 1950 writings on the psychology of the masses in fascist movements.

Yet the failure of the polls and left to predict the depth of Bolsonarista consciousness is also linked to the complete failure of the left—chiefly the PT but also allied parties—in mobilizing on the streets and in workplaces before and during the elections and offering a consistent progressive alternative. As in other parts of the world in the context of global capitalist crisis, the left and traditional centrist and right-wing parties have been incapable of providing solutions to basic socio-economic problems. The PT’s presidential platform is awash in watered-down promises to reverse the defeats of Bolsonaro, but embraces key tenets of neoliberalism such as fiscal responsibility, kowtowing to the banks and agribusiness, and waffling on the necessity for massive social investment to ameliorate one of the most unequal societies in the world.

The left election campaign this year was premised on a top-down, bureaucratic marketing conception of politics with few combative street mobilizations. It mistakenly relied on an illusory optimism fueled by the polls, eschewing a conception of frontal confrontation and combat against far-right ideology and politics. And it ignored the recent warning of the Brazilian rap legend, Mano Brown, that the left was lost without building its base in working-class neighbourhoods.

It’s abundantly clear that in the next weeks before the second round of presidential and gubernatorial elections (and after in the confrontation with the Bolsonaro-led Congress), the left needs to shift its institutionalist strategy and tactics to a political conception of mobilization, of occupying the streets and all possible political spaces to build expressive and visible support against the neofascist Bolsonaro project. This is the only way to save democracy in Brazil, rebuild the economy and society in the interests of the majority, and honour the memory of the 700,000 Brazilians who perished in the pandemic.

This article originally appeared in The Bullet on October 21, 2022. Thanks to Socialist Project for permission to republish here.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate