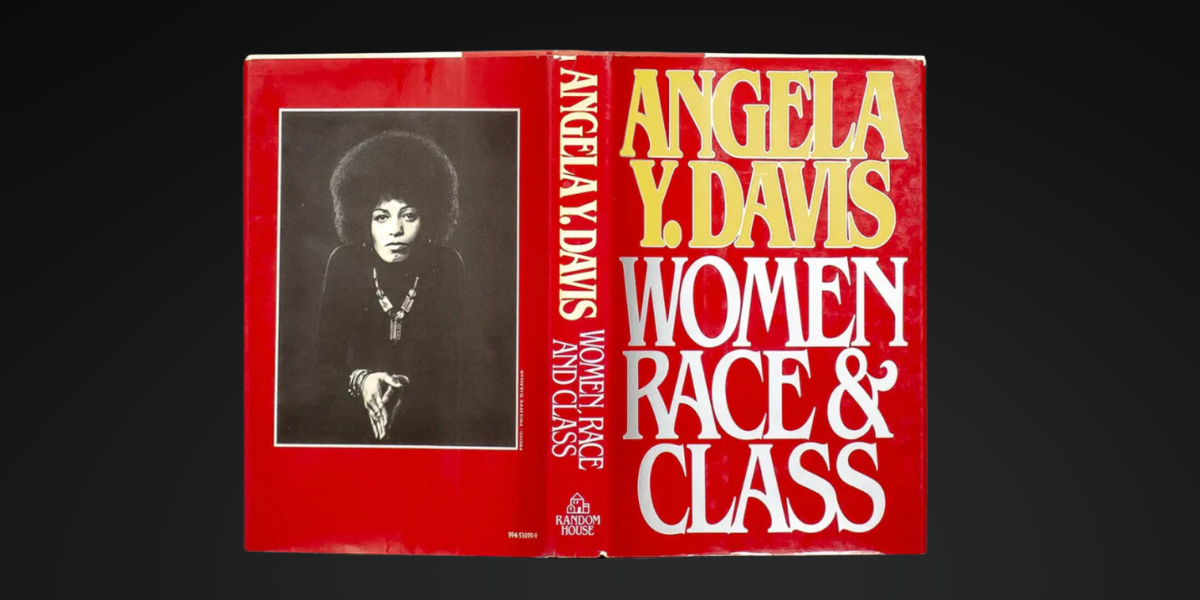

Angela Yvonne Davis is one of the most important living socialist scholars and activists in North America. Her books Are Prisons Obsolete? and Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement have been influential in activist circles as well as in academia, tackling prison abolitionism and settler-colonialism respectively. Women, Race, and Class, her classic 1981 book looking at the history of feminist movements in the United States and how they intertwined with labor and Black liberation movements remains essential reading for socialists.

Slavery and womanhood

Davis opens the book by positing that slavery impacted the way that womanhood is defined across races. While white women were expected to stay at home and raise the family, Black female slaves were expected to work just as hard as their male counterparts. Davis quotes Kenneth M. Stamp, “the slave woman was first a full-time worker for her owner, and only incidentally a wife, mother and homemaker.” The way motherhood defined femininity — “a by-product of industrialization” — in the 19th century did not extend to Black women slaves.

The roles undertaken by slave women and men in these situations were complex — they still believed in “marriage taboos, naming practices, and sexual mores.” This, Davis says, was a humanizing truth that contradicted much scholarship about the slave family, which believed it to be matriarchal and primitive. In reality, the slave family was surprisingly equal. While women might have sewed while men did the gardening and hunting, their domestic labor was not hierarchical — “they were both equally necessary.”

The analysis of womanhood and family life under slavery is only the first chapter. Davis also covers topics such as the interaction between the anti-slavery movement and early women’s rights movements, the importance of education in combating slavery and racism, the relationship between the labor movement and racial liberation, reproductive rights, and housework.

Liberation for all women

At every turn, Davis drives home the point that the fights for women’s liberation, racial liberation, and class liberation are incomplete without one another. For example, while anti-slavery and women’s suffrage movements fought together for the emancipation of Black slaves, they splintered when emancipation finally came without the vote for women. Some white women’s suffrage leaders went so far as to decry emancipation — Susan B. Anthony said she would rather cut off her arm than “work for or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman.” This form of activism ends up hurting the plight of women because it denies the existence of Black women — and without the liberation of Black women, women as a whole cannot be liberated.

Davis argues that one cannot fight for the liberation of women without fighting for the liberation of all women. Otherwise, it’s not “women’s suffrage,” it is “white women’s suffrage.” Susan B. Anthony’s behavior also ignored the Black women who remained active in the movement for women’s suffrage. They were not given special privileges over white women — they were still not allowed the vote. However, the white Women’s Suffrage leaders who chose to betray the cause of Black liberation exposed their racist biases. Their behavior illustrates the fact that they were not fighting for Black women’s liberation.

Class and women’s oppression

Davis also talks about how upper-class and middle-class activism ignored poor women’s fight for liberation. The movement was tunnel-visioned into furthering “women’s” causes. As such, the leaders encouraged women to scab (replace) male workers who went on strike. This might have given women more work, but they would have to deal with the working conditions that men were protesting in the first place. As such, women — when they scabbed — were subjugated to unsafe working conditions and betrayed the cause of female labor. This also points out another flaw in the feminist movement of the time — the idea that with the vote, women’s liberation would follow. They failed to see how their husbands, sons, and brothers were still economically subjugated by the bourgeoisie. Davis poignantly states, “political equality did not open the door to economic equality.”

Another important historical trend Davis brings up is the fact that socialists and leftists seem to have played important parts in the women’s suffrage and Black liberation movements. The women’s right to vote was seen by a large part of the movement as a tool for them to use in the ongoing class struggle. The vote could be used to improve working conditions, so socialist women joined the suffrage movement to further their cause and brought with them “a new energy.” Davis also points out that International Women’s Day is a celebration of the anniversary of a socialist demonstration for equal suffrage. In chapter 10, she focuses the lens on five communist women: Lucy Parsons, Ella Reeve Bloor, Anita Whitney, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and Claudia Jones. These five women differed in their reasoning, but they all had the same goal in mind: the liberation of everyone from racial, sexual, and economic exploitation. Davis gives us these women as an example in contrast to her critiques of activists like Susan B. Anthony, who in their quest to liberate people from only one form of exploitation failed.

Socialism and liberation

Economic liberation did not liberate the USSR from anti-semitism, China from Islamophobia, or Cuba and Vietnam from homophobia. Emancipation from slavery did not liberate Black people from economic exploitation in the form of wage slavery, penal labor, or conscription. Suffrage did not liberate Black men and women from Jim Crow law, nor did it prevent the Great Betrayal, nor the rise of the prison-industrial complex. It is only when we are liberated from all forms of oppression that we can be truly emancipated.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate