One year ago, I published an article outlining the legal challenge over trans rights and the notwithstanding clause going on in Saskatchewan. The Court of King’s Bench in Regina was faced with a dispute between the Government of Saskatchewan and the University of Regina Pride Centre over the Government’s Parents’ Bill of Rights, which restricted trans identity expression in provincial high schools. While the issue at hand was ostensibly one of social LGBTQ+ policy, the Court was also forced to answer a pivotal and groundbreaking question about Canadian constitutional law: what are the limits of the notwithstanding clause?

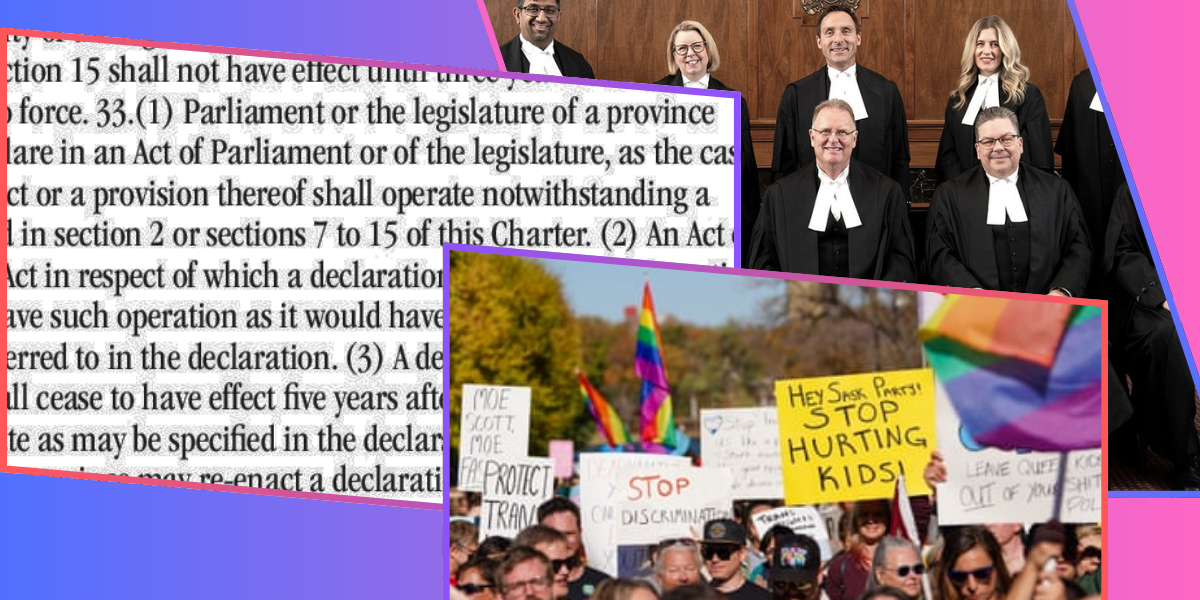

Section 33 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, commonly referred to as the notwithstanding clause, allows Parliament and provincial legislatures to infringe certain Charter rights if the legislation in question acknowledges that they are doing so intentionally. Section 33(1) reads: “Parliament or the legislature of a province may expressly declare in an Act of Parliament or of the legislature, as the case may be, that the Act or a provision thereof shall operate notwithstanding a provision included in section 2 or sections 7 to 15 of this Charter.” When invoking the notwithstanding clause, relevant Charter provisions are of no force or effect. Governments embed the notwithstanding clause in laws that would otherwise be struck down by the courts for impeding on Canadians’ Charter rights.

When the Government of Saskatchewan began formulating the policy that would eventually become the Parents’ Bill of Rights, the University of Regina Pride Centre sought an injunction against the government on the basis that this policy would violate Charter rights. In response to this legal challenge, Scott Moe’s conservative government stated that it would use the notwithstanding clause to protect the law from being struck down by the courts. However, this was not the end of the story. In a controversial move, the trial judge allowed the UR Pride Centre to amend and continue its lawsuit against the Government despite the invocation of the notwithstanding clause.

In my previous article, I outlined the recent debates among scholars about the scope and limits of the notwithstanding clause. Several scholars, such as Leonid Sirota, have argued that the judiciary might still be able to offer certain remedies to Canadians who have had their Charter rights infringed by s. 33-protected legislation. What these remedies might include is also debated: some argue that monetary compensation might be afforded, while others hold that the courts can offer a declaratory statement that a given law contravenes Charter rights, which could itself be a remedy. At any rate, this side of the debate sees the notwithstanding clause as essentially limited to protecting a law from being struck down. It does not necessarily protect remedies from being dispensed pursuant to s. 24(1) of the Constitution Act.

On the other side of the debate are scholars such as Geoffrey Sigalet, who hold that the notwithstanding clause, despite any ambiguity in the text of the Charter, has always been understood to be an expansive governmental power to impede rights-protection. Sigalet argued in an essay published in The Notwithstanding Clause and the Canadian Charter that even if courts had the legal power to review laws protected by s. 33, it would be politically disastrous, leading to activist courts and undermining parliamentary supremacy. The notwithstanding clause was formulated during the constitutional conventions because provincial leaders were worried about Charter provisions curbing their legislative authority. In light of this interpretation, many argue that the notwithstanding clause today should be given a wide scope.

Legal victory

On August 11th, the Court of Appeal for Saskatchewan took a side in this debate when it issued its ruling in Saskatchewan (Minister of Education) v. UR Pride Centre for Sexuality and Gender Diversity. In a decision that is already changing how legal experts and politicians think about the notwithstanding clause and rights-protection, the Court sided with the reformers, arguing that “Section 33 of the Charter…enables the Act or provision to operate regardless of whether it unreasonably limits a specific Charter right or freedom, by suspending the invalidating effect of s. 52 of the Constitution Act, 1982. A declaration made pursuant to s. 33 does not mean that the Act or provision does not limit the referenced Charter right or freedom – here being ss. 2, 7 and 15(1) of the Charter – nor does it nullify the jurisdiction of the Court of King’s Bench to issue a declaration to that effect.” In other words, courts are within their jurisdiction to dispense declarations of infringement in regard to laws that have been protected by the notwithstanding clause, just as Sirota argued.

The Court of Appeal left the door open for further developments on this issue, noting their subordination to the Supreme Court. Scott Moe’s government previously stated they would appeal if the Saskatchewan courts ruled against them. If appealed, this landmark decision could be relitigated by the Supreme Court and possibly overturned. At any rate, litigation within Saskatchewan will continue at the Court of King’s Bench. For the time being, however, the notwithstanding clause has taken on a new meaning in Canada.

The struggle continues

But at this point, after a victory and vindication for the UR Pride Centre, it is important to take a step back and reassess the situation. It has now been acknowledged that the Government of Saskatchewan’s law is discriminatory against trans youth, infringing their Charter rights, but where does this leave us? At the end of the day, monumental as this ruling is legally, affected youth in Saskatchewan are in the same situation. The Parents’ Bill of Rights still requires that Saskatchewan students under 16 receive written parental consent in order for a teacher to refer to them by a preferred name and set of pronouns.

What this emphasizes are the limitations of the legalist struggle. In issues of social justice, courts can sometimes offer substantial remedies, especially in Indigenous rights and title cases. Other times, courts are much more limited. At best, the Court of King’s Bench might offer ‘declaratory relief’ (a judicial statement that declares that the legislation contradicts the Charter rights in question), but no more to the affected queer youth in Saskatchewan. This insufficient victory emphasizes the importance of the political struggle as well as the legal.

Organization to oppose the Government of Saskatchewan is just as, if not more important than pursuing legal action. As socialists, we must not adopt Legal Marxism, a movement in which our strategies and aims are watered down to fit within the bourgeois legal paradigm of the Canadian state. Queer liberation, along with the emancipation of workers and all exploited peoples, can only be achieved through concerted revolutionary action.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate