“Workingmen’s Paris, with its Commune, will be forever celebrated as the glorious harbinger of a new society. Its martyrs are enshrined in the great heart of the working class.” – Karl Marx, The Civil War in France, written at the time of the Commune.

March 18 marks the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune, the first workers’ government. To learn about the Paris Commune is to learn an incredibly important part of our history. We learn about the savagery of the ruling class when it is under attack, and we are inspired by the courage, vision, and internationalism of the Communards.

Origins of the Commune

Paris was, at the time, the second largest city in the world after London, and had a population of over 1.8 million by 1870. It was the political centre of the world, and there had been revolutions or overthrows of governments in France in 1830 and 1848, and many insurrectionary incidents in the years that followed. Leading up to 1870, Napoleon III was in power and his government amounted to a police state, which kept down workers. But France was also the largest section of the First International, or the International Workingmen’s Association, of which Marx and Engels were early influential members.

Napoleon went to war because his repression at home had not succeeded in stopping strikes or the growth of the International. He needed a foreign distraction to pull the country behind him, and chose a war with Prussia over the issue of who would ascend to the vacant Spanish throne. The main reason he lost this war was because he and the rest of the ruling class were terrified of recruiting and arming a mass army, of giving guns to the workers. As Adolphe Thiers (who would later become the President) said, “it is not safe to place a gun on the shoulders of every socialist.”

The war against Prussia began in July 1870 and within two months, Napoleon and some several thousand French troops were captured. Immediately afterwards, crowds of Parisians invaded the Legislative Assembly and the City Hall and declared a new, republican government on September 4, 1870. Everyone, except royalists and the defenders of the old empire, was thrilled that the Napoleonic dictatorship was gone. The Parisian deputies to the Legislative Assembly formed a provisional government. Many hoped that an armistice with Prussia would be reached immediately. When this did not happen, Parisians turned to the task of preparing the city to resist. In September 1870, the Prussian siege of Paris began. At the end of January 1871, the Government of National Defence accepted Bismarck’s armistice terms and surrendered the city to the Prussians.

The workers are armed

The French held elections for a National Assembly, which in turn selected the elderly and extremely conservative statesman Adolphe Thiers to lead the government. Appalled at the government’s capitulation to Bismarck’s terms and angered that the Prussian troops who had starved and bombarded Paris were to be allowed to humiliate the city with a triumphal march, the Parisians grew daily more suspicious of the government’s motives. Working class neighbourhoods barricaded themselves. Cannons that had been left in the zone to be occupied by the Prussians were dragged by hand to the hills of Paris for safekeeping.

The French Government of Thiers decided that unpaid back rents had to be paid up, which was impossible because there was no money due to mass unemployment. The government also said that all debts incurred during the war had to be paid, and then the government stopped paying the National Guard. It suppressed radical newspapers. It sentenced the working class leaders Auguste Blanqui and Gustave Flourens to death in absentia. And it moved the capital of the country from Paris to Versailles, the historic centre of French royalty.

The Versailles government wanted to disarm the National Guard. The government’s army went to Montmarte, a working class neighbourhood, to remove the cannons. The National Guard became aware of this attempt and one of the Communards who led the resistance was Louise Michel. Michel described the situation in Montmartre: “It was an ocean of humanity, but there was not death, because the women threw themselves on the cannon, and the soldiers refused to turn on the crowd.” Later that day, two senior French military officials were killed by their own soldiers.

As Val Morel of the Central Committee of the National Guard, said “This fighter had dreams for fifty years and now he was living his dream, and seeing businessmen humbled, begging for an audience. At last.”

Dual power and democracy

By March, there was a situation of dual power, with the National Guard in Paris, and the ruling class government moved outside Paris, to Versailles. Even though the National Guard at one time had been bourgeois, it had become working class in makeup. The wealthy had left Paris during the winter, leaving the workers armed in the National Guard.

The Commune emerged on March 18, 1871, out of material conditions that drove the masses into action. First, the siege of Paris cut off the city from the rest of world (except by air balloon), and there was total economic collapse. Secondly, the winter added to a food and heat crisis. The government did not ration food so the wealthy did just fine—eating the animals in the zoo, horses, cats, dogs and rats—while the masses starved. Thirdly, while the government talked about defending the country, it preferred surrendering to Prussia than giving power to its workers. It had set up the National Guard, essentially a citizens militia, and lots of unemployed workers joined up. Now there was a mass, organized, and armed working class.

The ruling class was now more terrified of its own working class citizens than it was of the Prussians. And for good reasons. The National Guard was democratized: officers were elected, there were instant recall provisions, and there was no extraordinary pay for senior officers. This became the basis for the workers’ democracy the Commune tried to develop. So there was working class unity, democratic control, and centralization to take on the ruling class. This was something brand new, a mass and democratic movement from below to create a new society.

The National Guard Central Committee, arrondissement mayors, and Parisian deputies instituted self-rule for Paris, announced city-wide elections and tried to negotiate with the government in Versailles to reach a peaceful solution to the crisis. On March 28th the Paris Commune officially came into existence. The newly elected municipal council was inaugurated at the city hall, or Hotel de Ville, and began to undo the decrees of the National Assembly.

Achievements of the Commune, including the role of women

There was workers’ control of the workshops, most of which had been deserted by the owners who had fled Paris. Workers introduced a minimum wage and brought in the trade unionists to discuss how to run industry. By democratizing society, crime rate plunged.

Workers introduced civil divorce and put an end to so-called “illegitimacy” of children born out of wedlock. Workers took over Churches as municipal buildings, with church service during the day and discussion clubs at night. It was largely women at these mass meetings, as it was mainly men who were on the front lines militarily. They discussed what the church considered “scandalous subjects”, like divorce and opposition to the clergy. There was an end to the religious control of education. Education became open to all children, so that they could learn justice and equality, or as one school principal put it, “so the strong and powerful do not crush the weak.” The thinking was that children needed to learn to speak, write and have a trade. As they said, “A person who wields a tool must also be able to write a book.”

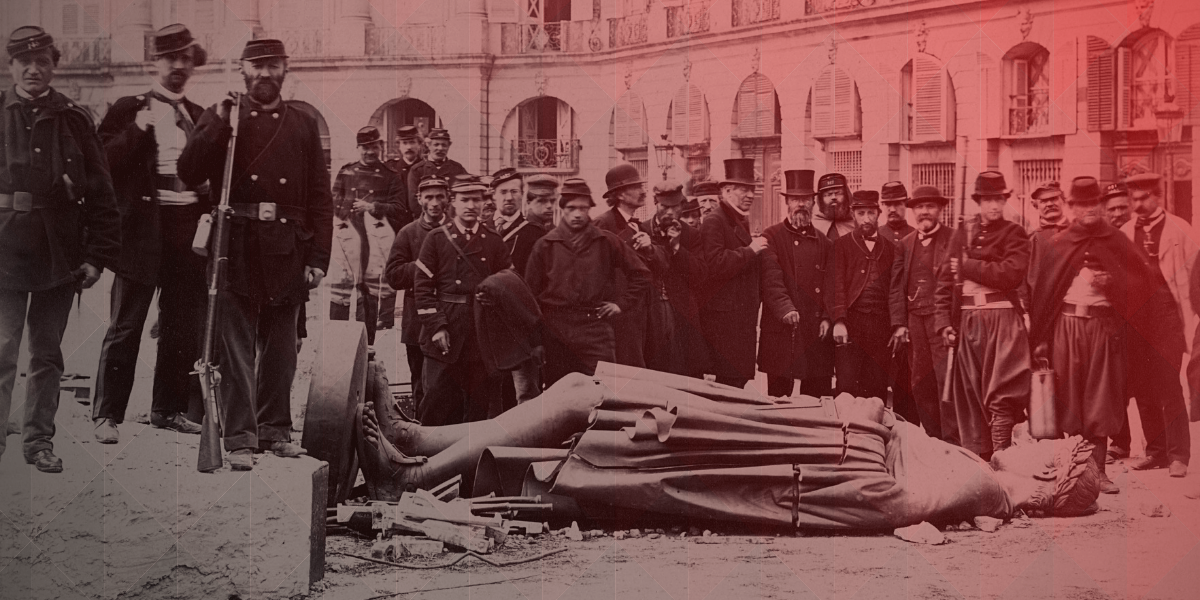

Another notable achievement of the Commune was its internationalism. This feature was particularly detested by the ruling class, which had tried to use xenophobic war to divide the working class. But nationalism broke down during the Prussian siege in response to class privileges, and internationalism emerged. Commune leadership included Dumbrowski of Poland, Frankel of Hungary, and Garibaldi was nominated from Italy. As a symbol of international solidarity, the Commune took down the “Victory Column” at Place Vendôme that glorified French military victories.

Women’s oppression didn’t instantly disappear, but women made strides towards liberation in the new democratic context. Relegated to the margins of formal politics by a so-called “universal” suffrage that excluded them, women found their own ways to express their support for the Commune. They were active in the Vigilance Committees and prepared to defend the barricades. Female orators denounced the government and the National Guard for cowardice and ineptitude. Female cooks, water carriers, and medical assistants accompanied the battalions of the National Guard into battle. Women workers manufactured gun cartridges, uniforms, and sacks to be filled with sand for the barricades. Andre Leo (Leodile Champseix), the female editor of the Commune newspaper La Sociale, warned the Commune and National Guard leaders about the dangers of alienating women’s support. Louise Michel joined the National Guard in battle. Elizabeth Dmietrieff and others members of the First International founded the Union of Women for the Care of the wounded and the Defence of the Commune.

While the Central Committee of the National Guard had instant recall for its members, this was not the case for the Commune itself. The Commune was set up by municipal elections, which meant, for example, that women couldn’t vote, and there was no provision for instant recall. The Commune followed the municipal election route because they were trying to avoid an all-out civil war. Ultimately, this didn’t work because the ruling class would fight whatever the Commune did. But the Commune did fix the wages of its workers at the level of skilled workers, and did approve the principle of instant recall.

So people were mobilized and armed. They saw the Central Committee as what they called “servants of the people. The people are tired of saviours.” The Commune would organize huge mass meetings, attended by 3,000 to 6,000 people. And the people bombarded City Hall with their ideas on how to run society.

The ruling class re-asserts itself

On the surface, the situation looked hopeful, and the Commune sought to negotiate with Thiers for Parisian home rule. But Thiers and his National Assembly refused to negotiate, understanding the revolutionary implications of what the Commune stood for. Had the Commune seized the momentum and marched upon Versailles, it could have defeated the badly demoralized French army. But as the Louis Antoine de Saint-Just warned during the French Revolution a century before, those who make revolution half way dig their own graves.

While the Commune hesitated, Thiers began to build an army that would remain loyal to its officers and could be used to destroy the Commune. Loyalty was not a problem for the National Guard, but preparation, leadership unity, and coordination of supplies distribution were. On April 2nd the Versailles troops attacked the suburb of Courbevoie, pushed the National Guard back, and captured the bridge over the Seine into the suburb of Neuilly. The military civil war had now begun. The next day, the National Guard marched toward Versailles. But by evening, it was clear that enthusiasm and numbers had not been enough for victory. The army had remained loyal to its commanders, fired on the National guardsmen, and routed them.

Thiers was not inclined to be gracious in victory. On April 6, he increased the pressure on Paris by bombarding the western sections of the city. In a terrible foreshadowing of things to come, the Versailles troops executed some of their captured prisoners on April 3 and 4, including two National Guard generals, and allowed others to be abused by crowds in Versailles. In retaliation, the Commune took a variety of hostages, including the archbishop of Paris and several priests, and threatened to execute them if Versailles continued to kill its Communard prisoners, a threat it did not carry out until May 24, during the final battle for the control of Paris.

As the war continued, propaganda disseminated by Versailles had turned people, particularly the peasantry outside of Paris, against the Commune. No one outside Paris, either in the provinces or in significant numbers from other countries, came to the city’s assistance. Still, most Parisians found it impossible to believe that French troops would actually invade the city and kill its citizens. But on May 21st, the Versailles army entered Paris through an unguarded gate and instituted a seemingly endless nightmare of street fighting followed by the surrender and then the execution of the Commune’s defenders. Trapped in the city by the Versailles troops on one side and the Prussians on the other, the Communards retreated from barricade to barricade. The Versailles troops killed 15,000 Parisians while entering the city, and slaughtered another 30,000 once inside. Those who survived faced trial and incarceration: 10,000 Communards were convicted, 23 were executed, 4,500 were incarcerated, and 4,500 more were deported to Australia.

Finally in 1880, when the republicans gained control of the National Assembly and the presidency of France, a general amnesty was granted to the Communards, and they were allowed to return from exile. Greeted enthusiastically by the French Left that had worked for their return, the thousands who had suffered in French prisons, languished in exile in London, Switzerland, or Brussels, or endured the hardships and futility of life in New Caledonia, resumed their lives and their political interests. The Mur des Fédérés (Wall of the Communards) in the Père-Lachaise Cemetery, where the Commune’s last defenders perished, became a place of pilgrimage to this day for admirers of the Commune from around the world.

Legacy of the Commune

The Commune marked a historical transition point, between the French revolution of 1789, with its slogans for the ruling class, and the Russian revolution of 1917, with its slogans for the working class. The key lesson, which Marx learned and theorized from the experience of the Commune, was that the existing state couldn’t be taken over and that a new one had to be built: “The working class cannot, as the rival factions of the appropriating class have done in their hours of triumph, simply lay hold on the read-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes.” There was greater clarity of what needed to be done, and this helped the Russians in their revolution. Whereas the Commune was limited in terms of geographic reach, timeframe, and achievements, the revolution of 1917 spread through the whole of Russia and was part of a global wave of struggle against capitalism and imperialism.

From Paris 1871 to Russia 1917, and from Egypt 2011 to Sudan 2019, capitalism continues to spark revolution. We need to learn from the strengths and limitations of all of them, so that the global experience of working class struggle can help us build a better world. The spirit of the Commune is wonderfully captured in the song “The International” written by Communard Eugene Pottier. Sung in languages around the world even today, the lyrics, some of which are below, continue to inspire:

No more

tradition’s chains shall bind us

Arise, ye slaves, no more in

thral

The earth shall rise on new

foundations

We have been naught, we

shall be all.

’Tis the final conflict

Let each stand in their place

The International working

class

Will be the human race.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate