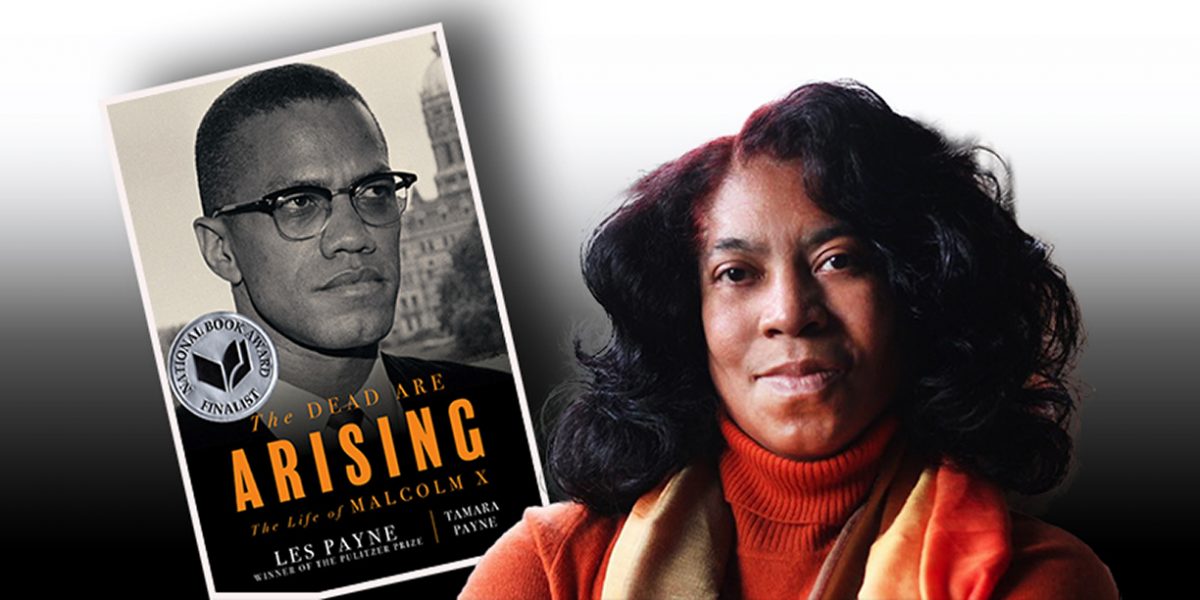

The Dead Are Arising: the Life of Malcolm X, by Les Payne and Tamara Payne (Liveright, 2020).

For many revolutionaries, The Autobiography of Malcolm X is a seminal text, a captivating story of African American resistance to racism told through the eyes of an icon of the movements that challenged white supremacy in the 1950s and 1960s. Malcolm’s recount of his journey from street hustler in the 1940s to lead spokesperson of the Nation of Islam in the 1950s, and then breaking away from the most reactionary elements of Black Nationalism in the last year of his life, remains one of the most gripping firsthand accounts of the making of an American radical.

There have been efforts to broaden the account of Malcolm’s life, the most significant being Manning Marable’s Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (full disclosure, I haven’t read Marable’s Pulitzer winning book). Les Payne, a renowned African American journalist who had met Malcolm in the later years of his time with the Nation of Islam, began researching his own biography in the early 1990s, after meeting an interviewing some family members of Malcolm’s and realizing there is an even richer story to be told. Payne died in 2018 prior to the completion of The Dead Are Arising: the Life of Malcolm X, but his daughter Tamara Payne put the finishing touches onto the manuscript and released the book this year to much acclaim—winning the National Book Award for Non-Fiction last month.

Political developments

The most revelatory aspects of the Paynes’ new book is the detailed account of Malcolm’s early years. Although Malcolm’s biography offers a lot of insight into the troubled youth that led him to hustling and crime, The Dead Are Arising also provides a deeper account into the rich political tradition that surrounded him from an early age.

Earl Little, Malcolm’s father, was a Baptist preacher but also an early convert and spokesperson for Marcus Garvey’s Back to Africa movement. Malcolm would regularly go with his father to speaking engagements and take in the radical Black Nationalism that Garvey and his father espoused. He would have also seen the downfall of Garvey, partly the result of the state’s persecution (shamefully supported by political rivals including W.E.B. DuBois) but also from Garvey’s own tactical mistakes that included allying with the Klu Klux Klan around the common goal of Black migration back to Africa—a mistake that Malcolm worried the Nation of Islam was making in his later years. The Dead Are Arising portrays a childhood filled with the political conflicts that Malcolm found himself in the middle of years later, helping us to understand how he was drawn to the Black Nationalism of the Nation of Islam and why breaking from tenets of it in the early 1960s would be such a personal challenge.

Malcolm’s autobiography provides a thorough account of his religious awakening as a Muslim while incarcerated in the early 1950s and his meteoric rise to national spokesperson for the Nation of Islam. However, it also leaves us blindsided in how quickly he was isolated and pushed out in 1963. Malcolm famously told Alex Haley, who recorded the work and produced it into a book after Malcolm’s death, not to go back and change any details that he had told Haley prior to his break from the Nation. The Autobiography comes off as incredibly sincere and earnest as a result, with Malcolm’s ideas changing before our eyes, but leaves us shocked in how quickly the disillusionment of the relationship between Malcolm and the Nation occurred.

The Dead Are Arising fills in a lot of gaps, offers a rich history of the Nation’s emergence and reveals a more nuanced timeline of Malcolm’s political development. The Nation was formed in 1930 under the leadership of Wallace Fard, who claimed to be from the Middle East but appears to have been white and a long-time grifter. That he would create a Black nationalist organization that stood for the separation of races and the vilification of whites is ironic, but an irony that Fard’s successor, Elijah Muhammad, largely ignored while suggesting that that Fard was in fact Allah and Muhammad his prophet.

What emerged was a very specific brand of Islam that ran counter to most Muslim interpretations of the faith. These contradictions were ones that Malcolm constantly grappled with. He would engage with non-Nation Muslims who challenged its racial exclusionary positions and continue relationships and dialogue with them. When Muhammad sought to make informal allyships with the KKK in the Deep South, Malcolm was significantly more cautious than his leader, suspecting what any sort of agreement with the hated white nationalists could look like, having seen how this kind of olive branch killed Garvey’s movement decades earlier.

From separatist to revolutionary

When Malcolm became the star preacher for the Nation, he immediately adapted a more aggressive approach to building up the Nation of Islam, recruiting more broadly than Elijah Muhammed, and seeking to engage the national media in hopes of growing the organization and building the political power to win the Nation’s larger demands of a separate Black state.

As Malcolm’s profile and popularity grew and with the membership ranks expanded as a result of his abilities and efforts, tensions emerged among Muhammad’s family, worried that Malcolm would interrupt the succession planning they had counted on. The Paynes refer to Muhammad’s children as “the Royal Family,” a group that had grown accustomed to the riches brought in with an expanding membership. The Royal Family also appeared to flout many of the most sacrilege practices of the religion—eating pork, engaging in adultery and fathering children out of wedlock. It is the latter of these that set off the rift that pushed Malcolm out of the Nation. When he began questioning the numerous accounts of Muhammed having children with his young secretaries, the leader sought to isolate the national spokesperson and used Malcolm’s “chickens come home to roost” response to the JFK assassination to discipline him.

The most significant shortcoming of The Dead Are Arising is the concluding chapters dealing with the last year of Malcolm’s life—when he broke from the Nation, performed his hajj to Mecca, embraced the possibility of cross-racial organizing, and formed the Organization of Afro-American Unity. This was a whirlwind moment in time and there was not much time for Malcolm to hash out his quickly changing ideas, but the Paynes quickly turned away from the significance of these organizing efforts to delve into Malcolm’s assassination in February 1965 and who was truly responsible for his death.

Although re-examining the assassination is trendy at this moment (with a six-part Netflix series focused on it), as a socialist, I wish the Paynes had delved a little more into Malcolm’s ideas at this moment. They note some things, like Malcolm’s famous quotes “You can’t have capitalism without racism. And if you find a person without racism and you happen to get that person into a conversation and they have a philosophy that makes you sure they don’t have this racism in their outlook, usually they’re socialists or their political philosophy is socialism.” However, considering the depth of research in most of this book, the examination of Malcolm’s last year is filled with already known facts and ideas and feels rushed.

As anti-racist movements across North America continue to grow in numbers, the experience of Malcolm X and the lessons learned from his entire life, including as a militant organizer are still relevant. The ferocity of his opinion, the unbending will he had in the most trying of times, and his move toward broad anti-capitalism toward the end of his life continue to offer lessons for organizers today. The Dead Are Arising is a strong addition to our understanding of Malcolm, and for anyone interested in further studying the how and why of Malcolm’s importance it is a great resource.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate