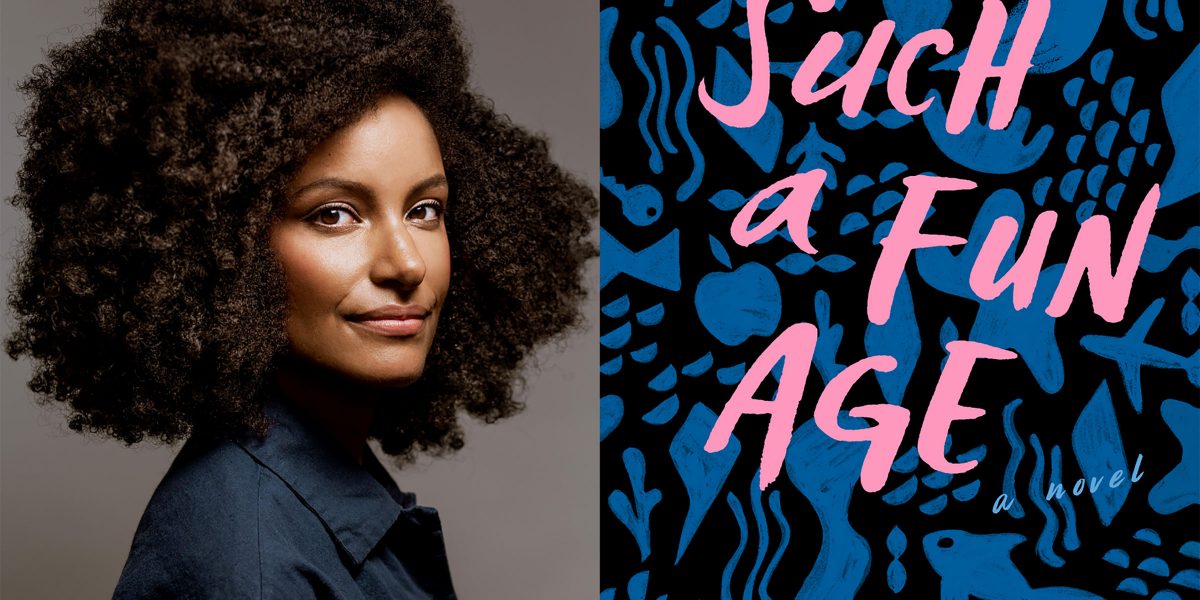

Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2019).

Kiley Reid has written a powerful book about being Black in white spaces in contemporary America. Long-listed for this year’s prestigious Booker Prize, Reid’s Such a Fun Age provides a uniquely powerful view of white supremacy through a story in which all the white characters love (or at least claim to love) Emira, the 25-year old Black woman at the novel’s centre. What makes it a book about structural racism is not just that the love is smothering, condescending, or unearned; rather, Reid traces how the very emergence, deployment, and termination of affection for Emira is, at every moment, structured by the needs of whiteness.

Emira is a baby-sitter for the Chamberlains, a well-off white family in Philadelphia. She loves spending time with her three-year old charge, Briar, but feels growing shame at not advancing through a professional career, as well as fear at the prospect of losing her parents’ medical coverage. Her girlfriends are becoming junior sales executives making $30,000 a year plus benefits. Emira went to college and typing school, and transcribes part-time here and there. Nevertheless, she feels stuck: sharing an apartment with someone from craigslist, no clear path to success.

Early in the book, Emira is harassed by white customers, clerks, and a security guard while minding Briar at a posh grocery mart. She and the little girl are only there in the first place because the Chamberlains suddenly asked Emira for emergency child care at 10pm on Friday night. Everyone in the shop is suspicious: why is Emira there, dressed as she is, so late with this obviously-not-hers child? Briar’s father swoops in before the scene gets as bad as it could get, but it’s scary and maddening to witness how quickly and aggressively the beneficiaries of whiteness go on the attack. We’ve all seen videos of similar scenes that end in anti-Black violence and death.

Emira is angry, but not so much. She’s just glad it’s over; she wants to move on. Turns out, though, that a good looking white guy in a Penn State shirt recorded the scene on his cell phone. He tells Emira she should go public with it, sue the grocery store, make a fuss. Emira declines. Maybe someone else would do that, she says. She simply doesn’t want the hassle.

The cute guy, Kelley, becomes a love interest. Without wanting to give too much away, that gets very complicated when he enters the orbit of Emira’s employer, the Hillary Clinton-loving, successful-white-feminist-start-up-running, book-writing, self-branding, Alix Chamberlain.

The plot from there is a tug-of-war between Kelley and Alix over Emira’s loyalty, affection, and obedience. It’s never primarily for Emira’s benefit that Kelley and Alix instruct and guide her. In fact, the efforts to win Emira’s affection – by being casual or dumb about race, by offering better pay, by throwing lavish feasts, by sniping at each other – are often transparently selfish, if not racist, too. But throughout the book, Reid salts scenes and memories with enough ambiguity that Kelley and Alix’s actions are rarely simply transparent, deliberate manipulations. Ultimately, Alix does deceive Emira; but even then, it’s ostensibly done for Emira’s own good. In a deft move to demonstrate the strength and sprawl of white supremacy, Alix’s flagrant breach of trust is supported by her Black friend, Tamra (who Emira’s wonderful friend Zara eventually calls an “Uncle Tom”).

What Reid does so effectively is use Emira’s perspective to open up space for more sympathetic readings of the problematic race and sexual politics of Kelley and Alix. Not to absolve them of their faults, but to highlight the exhausting emotional labour they constantly force upon Emira. This felt especially important for me, a white reader, to observe and learn from.

One of the virtues of the novel as an art form is its ability to offer multiple perspectives on the same situation. Different characters see the world differently. Authors often show readers the story through the eyes of different characters in order to foster sympathy for something or someone that, on its own, looks bad. Typically, this is accomplished by getting inside the head of the character we’re meant to sympathize with. The fresh twist in Such a Fun Age is thatKelley and Alix are often the worst when we see them on their own terms. It’s when Emira mediates their actions, often responding to one about the other, that we’re able to think, “Hmmm… yeah, OK, maybe that’s not as bad as I first thought?”

It’s Kelley who’s outraged that Emira wears a uniform while babysitting, not Emira. It’s Alix who demands that Kelley be punished for what he did in high school. Emira says, “This was all like… sixteen years ago, right? […] So yeah, I don’t know. I also did some really dumb things when I was in high school.” You want to side with Emira because the others are so obviously gross. But Reid doesn’t always make that easy: sometimes siding with Emira means giving whiteness a pass.

At the same time as it’s politically fascinating, the book is also a lot of fun. The gripping plot is filled with rich and real-seeming conversations among minor characters. It’s delightful to spend pages listening to Emira’s friends tease and cheer each other on. There are two hilariously suspenseful set-pieces at the Chamberlain home: one at Thanksgiving dinner, to kick the plot into high gear; the other at a televised interview toward the end of the book. Reid serves up schadenfreude by the gravy boat.

Critics have complained that Emira isn’t a strong-enough protagonist to carry the book. This misses that part of the daring brilliance of Reid’s novel is placing at its centre a relatively unremarkable, apolitical, unsure, self-doubting, kind and friendly Black woman. Emira is supposed to be passive!

Yet what stands out is not her passivity but the strength of Emira’s ability to do all that emotional work navigating white space. She’s constantly dealing with all sorts of problems that white people have thrust upon her. Kelley and Alix would say, “But we’re helping her,” ignoring the fact that they created the problems in the first place. Emira manages them; she has to. But that’s not because she’s weak, it’s because she’s navigating one pathway to survival in a white world. Anyway, it’s misguided to fault this novel because of something missing in one character or another. This was never supposed to be a story of individual heroes and villains. It’s relationships that Reid wants us to think about; and not just relationships among individual people, but rather relationships between paid and unpaid labour, between private and public spheres, between social expectations and limited opportunities. This is a truly social novel. I hope Kiley Reid writes many more of them

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate