Last week, sex workers and support organizations awoke to a disappointing decision from the Ontario Superior Court of Justice. The case, brought by the Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform, marked the latest effort to challenge harmful sex work laws in Canada due to parliament’s failure to repeal sex work offences.

Heard initially over four days in October 2022, Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform v. Attorney General (CASWLR v AG) challenged offences that sex workers argue are unconstitutional. This includes restrictions prohibiting selling sexual services in public, purchasing sexual services in any space, procuring, earning a material benefit from sex work, and advertising.

The coalition that sought to bring down these unconstitutional prohibitions includes not only the Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform (representing over 20 member organizations), but also multiple intervenors advancing human rights, racial justice, migrant solidarity, and sexual and reproductive justice.

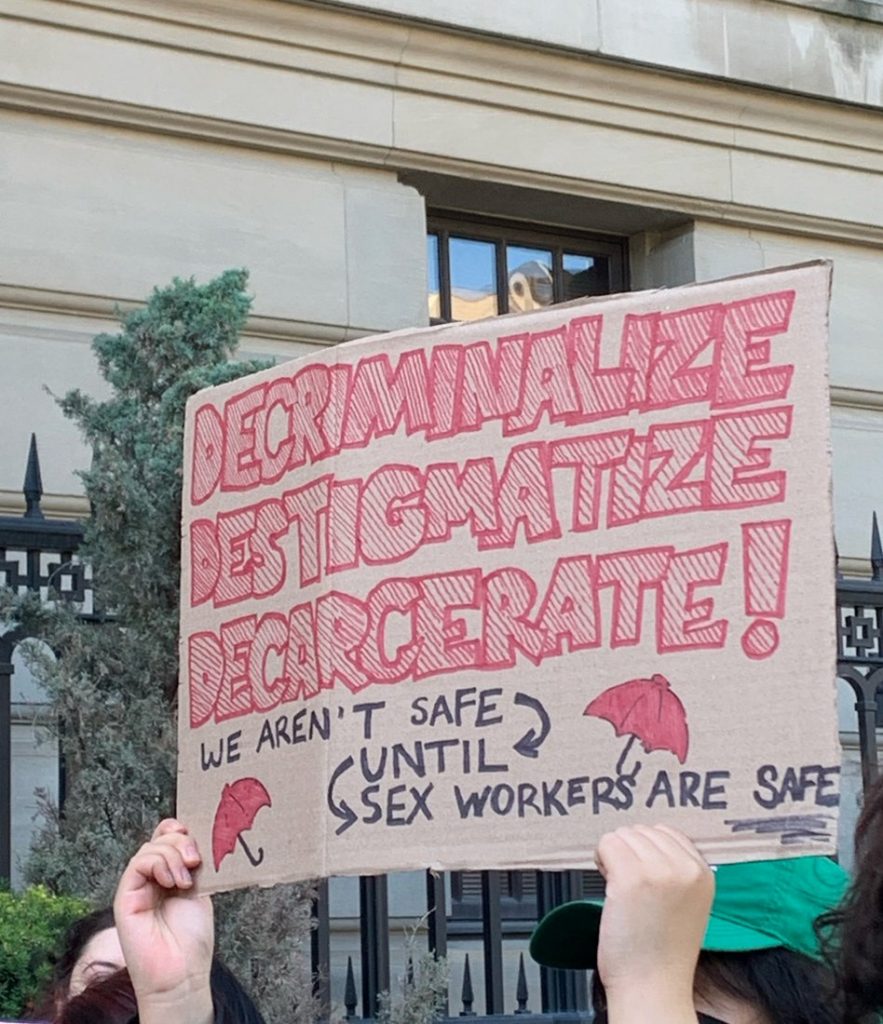

Across Canada, advocates maintain that the full and unapologetic decriminalization of sex work offers the most protection to those who engage in any aspect of sex work – especially those whose living and working conditions are constrained by intersecting oppressions.

The Ontario Superior Court’s decision outright dismissed the concerns raised by sex workers, academic experts, and fact witnesses with lived experience, noting “the expert must, however, abandon advocacy when giving their opinion…An expert can become so identified with a particular position that they become partial, and their evidence inadmissible” (CASWLR v AG, s. 110).

The court errs when categorizing certain academic experts as advocates. Research methodologies that centre sex workers do not detract from their analysis as experts. Instead, they can illuminate some serious challenges that sex workers engaging with research face – including access to a safe, confidential, and non-hostile environment to report on their realities.

Bad laws and worsened working conditions

In 2013, applicants Terri-Jean Bedford, Amy Lebovitch, and Valerie Scott (all of whom have lived experience in sex work) challenged three major prostitution provisions because they were unconstitutional and harmful to the rights to liberty, security of the person, and freedom of expression and association of sex workers. Their case, Canada (Attorney General) v. Bedford, led to multiple sex work-associated offences declared unconstitutional.

Following the decision, the Supreme Court gave Parliament one year to respond. The federal government, led by then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper and then-Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada Peter McKay responded with the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act (PCEPA), which remains in full effect today. PCEPA’s primary objective is to eradicate sex work and protect society from sex work itself, not to protect sex workers from the harm they encounter in society. The federal government’s FAQ on PCEPA still states, “The new prostitution laws are intended to reduce both the purchase and the sale of sexual services.”

This court decision directly contradicts the findings of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights Review of PCEPA in 2022. The committed states, “the Government of Canada must recognize that protecting the health and safety of those involved in sex work is made more difficult by the framework set by the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act and acknowledge that the Act causes serious harm to those engaged in sex work by making the work more dangerous.”

Overpolicing and underprotection of sex workers, made difficult by PCEPA, is also witnessed in BC. There exists an unpredictable legal landscape for sex workers regarding their safety, as they are easily subjected to discretionary enforcement and policing practices, made possible by the Sex Work Enforcement Guidelines that claim not to surveil sex workers but continue to surveil and arrest sex workers’ clients while in their presence.

While the decision in CASWLR v AG claims that “sex workers enjoy immunity from prosecution for the sale of their sexual services” (s. 346), the evidence submitted demonstrated that sex workers – particularly Black and migrant sex workers – continue to be arrested while performing “third party” tasks. As the Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform explains in a 2017 factsheet, “third parties are the people who work, provide services to, or associate with sex workers including: drivers, security, bookers, webmasters, business owners, receptionists of outcall agencies (e.g., escort agencies) or incall establishments.”

Advocates have been outspoken about PCEPA, and attempts to “end demand” through purchasing bans. In the 2017 research report Evaluating Canada’s Sex Work Laws: The Case for Repeal, Brenda Belak and Darcie Bennett question the logic of criminalizing the purchase of sex, noting “the eradication of sex work has yet to be achieved in any of the countries using asymmetrical criminalization. Unsubstantiated benefits of decreased demand need to be carefully weighed against real, documented harms experienced by current sex workers.”.

Regardless of one’s beliefs about sex work, criminalization and over-policing of already marginalized communities as a method of “saving” them are at odds with the well-documented harms of policing and criminalization.

Harmful myths pervade sex work law and policy decisions

Last Monday’s decision from the Ontario Superior Court emphasizes “the legal status of sex work is no longer ambiguous. The purchase of sex is prohibited” (CASWLR v AG, s. 3). The reasons for judgment also note that “the fundamental activity is now illegal. Sex workers had the right to sell their own sexual services in the pre-Bedford regime. They do not have that right under PCEPA” (CASWLR v AG, s. 236).

Some prohibitionist and religious groups have been proponents of PCEPA, and other major feminist organizations have historically shied away from taking a position.

As Chanelle Gallant notes in a recent Briarpatch article, Sex worker feminism, “SWERFs hold a key role in the far-right’s agenda: they craft the narratives that demonize trans people and sex workers as a threat to women like them and whitewash legal action as necessary defence of women’s rights.” The decision in CASWLR v AG reinforces violent assumptions about sex work – including assumptions about violence, autonomy, agency, consent, and the nature of exploitation in the context of sex work.

The decision states that “violence is a feature, not a bug of sex work” (CASWLR v AG, s 216). This statement is at complete odds with the analysis of sex work provided by Vancouver sex worker-led organization PACE Society. The court suggests that sex workers can, and should, expect violence in their lives. In Occupational Health and Safety training and other workshops presented by PACE staff, we always emphasize that violence is pervasive in society and not unique to sex work. Instead, violence must be understood as part of settler colonialism, white supremacy, ableism, misogyny, and transmisogyny. These systems shape every single industry and labour market. Equating violence with sex workers’ labour conditions invites violence into the lives of sex workers and treats sex workers as lesser or unworthy victims.

Sex workers have been targeted by predators who are taught that sex workers are perfect prey and that violence against them should be normalized. Also, predators know that people engaged in sex work have less access and motivation to use reporting mechanisms as they are less likely to be treated with fairness or respect by police and prosecutors.

In a city that has been plagued by police officers’ ignoring violence against sex workers (as well as other forms of misogynistic violence, including failures to adequately investigate #MMIWG2S), we cannot divorce comments like “violence is just part of the job” from the everyday realities that sex workers face.

The dismissal of violence as a feature of sex work leads to sex workers being considered “less dead” when violent predators target them. The concept of “less dead” is a horrifying way to describe living, breathing human beings. Lauren E. Fernandez explains this term, stating:

Sex workers have historically represented a disproportionate percentage of all victims of serial murder. Several serial murderers in the past thirty years have evaded detection for years, taking the lives of dozens of victims, by targeting sex workers, playing off the biases of society and law enforcement and counting on the halfhearted investigation techniques that often followed missing person reports for less valued members of society, or the “less dead.”

The idea that sex workers are “less dead,” a victim-blaming concept, is also reinforced in media, pop culture, and law. It shifts blame for state-manufactured violence and detracts from the importance of addressing the harms sex workers experience. Lauren E. Fernandez notes that decriminalization of all aspects of sex work is “the surest way to improve the safety of street-based sex workers and reduce high victimization of this marginalized group in crimes of serial homicide.”

For decades, sex worker support organizations have clearly reported the experiences of sex workers in their communities: violence is not part of the job, nor is the absence of autonomy and agency, even when sex workers’ choices are constrained.

We underscore that community members who face structural barriers including racism, ableism, poverty, housing insecurity and reliance on an increasingly contaminated illicit drug supply, have less employment and income-generating options and suffer the most serious brunt of over-policing and underprotection. These conditions are key drivers in the realities of street sex workers, who are working in the most precarious of conditions.

Like other communities that live or work in public space (including unhoused people, low-level dealers, binners, and street-based vendors), street sex workers have been outspoken about the harms of policing. These harms extend well beyond arrest and enforcement to further include the experiences of navigating police as an informal or street economy worker.

The decision in CASWLR v AG also conflates sex work with exploitation and trafficking, supporting the myth that all sex workers are helpless victims. Extensive evidence was submitted with sex worker testimony that sex work itself is not experienced as violence, rather the conditions that are caused in large part by criminalization create a context where exploitation can flourish. The conflation of sex work with human trafficking exemplifies social, political, and economic investment in both policing and charitable-saviour responses to the diverse needs of sex workers, and ignores the fact that sex workers can experience violence but do not always experience violence

In a 2023 research paper, Andrea Mellor and Cecilia Benoit explain their findings based on interviews with staff from seven sex worker organizations: “the diversity of the sex worker population described by participants paints a much broader picture of the industry than is reflected in much of the current sex work literature, governmental laws (i.e., the Criminal Code) and legislation, and conservative antiprostitution lobby groups.” This paper was part of a special issue of Social Sciences Journal that concluded decriminalization of sex work is the best evidence-based strategy to reduce harms experienced by sex workers internationally.

Understanding the Charter challenge of PCEPA

PACE, as a member of the Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform, was awaiting this decision. We optimistically hoped that the Ontario Superior Court would declare all current prohibitions on sex work-related offences unconstitutional.

The court relies on and reproduces arguments from police for the reasoning in its decision, unwaveringly accepts evidence from advocates for criminalization, yet completely dismisses the expert and fact witnesses who highlight the dangers of criminalization. They fully undermine the expertise of service organizations like Butterfly, when the expert testimony of director Elene Lam was given “no weight” (CASWLR v AG, s. 171). Expert witnesses like professors Chris Bruckert and Chris Atchison are undermined for taking “very public positions in favour of the decriminalization and regulation of sex work” (CASWLR v AG, s.109). Comments like this from the Ontario Superior Court, reflect how ingrained anti-sex work stigma is, and the ways it is used to systematically undermine empirical evidence that proposes policy approaches based on evidence.

The very public activism and lobbying of prohibitionist and anti-trafficking advocates is treated uncritically by the court. And the reasons for the decision reinforce the perpetual argument that more money needs to go to police for them to deal with issues that arise from sex work. Rather than seriously consider what experts offered, the Court decided to give more weight to the beliefs of police and anti-sex work campaigners than to the experiences of sex workers under criminalization.

Policing and enforcement won’t “save” sex workers

The decision from the Ontario Superior court highlights how effective pro-police and anti-trafficking experts are in the legal system. While the evidence of Elene Lam was wholly dismissed, a former Calgary police officer’s personal experience is considered valid when he states that he has never met a sex worker who engaged in the “sex trade” independently.

Even in a context where police are instructed to continue to enforce criminal sex work prohibitions, they are still able to make efforts to mitigate harms associated with criminalization for sex workers. The 2022 report By Us, For Us: A needs and risks assessment of sex workers in the Lower Mainland and Southern Vancouver Island makes a range of recommendations about police, ranging from improved reporting systems, to reform, and defunding. By Us, For Us research determined that many sex workers have interacted with police, but 59 percent of the survey respondents stated that they did not feel safer with available police presence while doing sex work.

Police are not an effective intervention to state violence, especially for Black, Indigenous and racialized migrant sex workers. Police forces across Canada are rooted in a violent, colonial history that shapes their contemporary enforcement efforts. When the court defers to police’s interpretation of PCEPA, it fails to acknowledge discriminatory, biased, and outright illegal actions police take, often targeting marginalized community members.

What next? How to continue supporting criminalized sex workers

While this case makes its way through the courts, PCEPA and other enforcement tools, such as prohibitions on migrant sex workers, continue to harm sex workers. Unfortunately, litigation and Charter challenges also rely on courts and elected officials getting things right.

If Canadian law and policy-makers are unwilling to acknowledge evidence that decriminalization is the legislative regime that offers the best protections for sex workers, we need to look beyond these institutions and build the alternatives we want to see.

In the meantime, sex worker-led organizations and allied agencies and individuals must build supports that directly protect the safety, liberty, and working conditions of their sex working members. This means amplifying the call to defund police and invest in community-based crisis response, providing robust harm reduction, supporting sex workers through mutual aid, and funding organizations that convene sex workers as people with experience, expertise, and political agents who can best outline the harms sex workers experience and the solutions they urgently need.

Law- and policy-makers rely on anti-sex work stigma to justify their decisions about legislation, policy, and enforcement regimes that target people who do sex work. Unfortunately, these moralistic positions fail to attend to the realities of sex workers, who are a diverse group of labourers existing across intersections of oppression, privilege, autonomy, and agency. Instead of investing in legal frameworks that harm sex workers, we need a societal shift towards the immediate decriminalization of sex work, occupational health and safety, and addressing oppressive conditions that impact workers in all sectors.

If you want to support sex workers in your community, here’s a few ways:

- Learn about organizations like PACE Society, which operates on a by, with and for sex workers model.

- Support fundraisers, like this gofundme for Maggies Toronto and Holy Trinity to help recover from a devastating fire that destroyed the Maggies office.

- Amplify the work of Butterfly: Asian and Migrant Sex Worker Support Network, and SWAN Vancouver.

- Challenge anti-sex work stigma that exists in your own communities (including left organizing spaces, feminist groups, workplaces, etc.).

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate