The Fall and Rise of American Finance by Stephen Maher and Scott Aquanno (Verso 2024).

How should socialists think about finance? This is a question that’s been asked and answered time and time again. However, the answer is often unsatisfactory. Maher and Aquanno provide a refreshing take on financialization that puts both academic and activist minded individuals on the right track when it comes to tackling contemporary capitalism. There’s no shortage of left leaning books about the rise of finance as a parasitic, speculative, and rent seeking force which has led to the decline of manufacturing, the hollowing out of industry and the end of U.S hegemony. Instead of repeating these worn-out tropes, Maher and Aquanno show the real necessity of finance to the functioning of American and global capitalism.

The Fall and Rise of American Finance Capital is a great introductory text for those looking to understand contemporary finance while also providing a base theoretical and history understanding of the topic. Financialization refers broadly to a process in which “money-capital—or the circuit whereby money is advanced and then returned with interest—achieves greater dominance over social life and the economy”.

In order to discuss the different instances of financialization, Maher and Aquanno divide their book into four broad historical periods of American finance, all of which show its importance to capitalist production.

Classic finance

Starting with the classical finance capital period (1880-1929), they outline the origins of corporate development and the centrality of banks in providing the initial financing in the form of credit needed for industrial mergers and acquisitions.

Financial capital in this sense refers to a specific form of capitalism in which relationships between industrialists and financiers are particularly close, to the point where their interests all but align. As Marxist theorist Rudolph Hilferding famously described it, the financiers became industrialists, in other words, money capital became finance capital. At this time, individuals such as J.P Morgan were at the helm of extensive networks of corporate control and helped guide the development of American capitalism through their own holding of corporate stock. This period ended with the stock market crash of 1929 and led to the breaking up of this particular connection between banks and corporations with the advent of New Deal regulation.

Managerial finance

What followed was the managerial period (1930-1979). With banks being limited in their ability, internal managers of corporations came to be central economic actors. Typically, narratives of finance present this period as one devoid of its influence, but Maher and Aquanno point out that this is the time when managers themselves internalized many financial activities to deal with changing relations of accumulation. Businesses started to learn how to borrow and lend on financial markets directly. More importantly, to deal with the myriad of different concrete productive activities that corporations engaged in with the development of multidivisional corporate models, general managers needed to become financiers, who sat at the top of the corporate ladder and welding abstract-money capital in whatever would lead to the biggest profit. Instead of the presentation of the “Golden Age” of capitalism as devoid of financial logics, Maher and Aquanno show that firms were financializing in ways that were crucial to the rise of neoliberal in the following decades.

Neoliberal finance

After the crises of the late 1960s and 1970s ended with the Volker Shock when the federal reserve increased interest rates dramatically, we saw the rise of the neoliberal period (1979-2008). The hegemony of industrial managers was superseded by a new form of financial power, which grew due to a number of factors, including the rise of global financial markets, the globalization of production, and the rise of shareholder power. Furthermore, union militancy in the preceding period also played a part in the rise of external financiers via pension plans. Earnings of the preceding period of high productivity were collected into huge pools of money-capital in the form of pensions to be reinvested in the market. Massive pools of profits and savings in the economy led to the development of huge institutional investors. This rise of institutional investors laid the groundwork for the asset management industry we see today. All of this led to the increasing influence of external owners of debt and equity on organizations, especially corporations.

The growth of “corporate raiders”, proxy battles, and shareholder ideology led to a resurgence of financial power, but not yet of finance capital. It was not again until the concentrated form of financial power that emerged in the early 21st century that we would truly see the return of finance capital. The financial crisis of 2008 brought an end to the neoliberal period, but unlike many would assume, it did not bring an end to financial hegemony. Instead, the state came in and unlike in the 1930s, they defended finance by protecting assets that became illiquid during the crisis. Now, the Federal Reserve, through its policy of Quantitative Easing promoted liquidity. This resulted in the inflation of assets such as equities (i.e., stocks), and led to an environment where asset managers thrived.

New finance capital

The rise of the Big Three (B3) asset managers, BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street, was part of a historical reconstruction of corporate power and the rise of a new finance capital (2008-now). The pools of money-capital that were produced in the neoliberal period now came to be concentrated into even bigger mega-pools, which become controlled by powerful asset-managers. The properties of the B3 as owners of corporations (in the form of equity) is that they are large owners, concentrated and diversified across the whole economy.

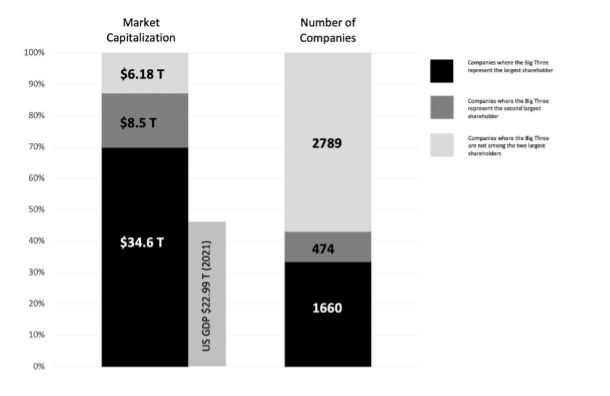

Typically, there’s a trade-off between being diversified and concentrated in the economy at large, but asset managers have overcome this, becoming true universal owners in the entire economy. The immense scale of this process cannot be understated. As the graphic produced by Maher and Aquanno outlines, the B3 are together the single or second largest owners in firms that constitute 90 percent of total market capitalization in the American economy. These firms together represent 45 trillion dollars in assets, basically double U.S GDP.

What mirrors their rise of universal status is the movement towards passive investment strategies. Passive investment involves holding stocks in one’s portfolio indefinitely, only trading to match the weight on different indexes. In contrast, active investment involves trading assets to ‘beat the market’. Passive funds have seen a huge rise in recent years as pointed out by the authors, now making more than half the equity funds managed since 2020. Indexes are themselves just collections of stocks like the NASDAQ of S&P 500, but they can be themed such as “green” investment based. Thus, asset managers have large “passive” funds, which simply trade to match the changes in the weight of certain stocks as a part of an index.

The rise of passive management brings us to a central question that the authors attempt to answer. How have recent changes in capitalism led to the rise of a new finance capital in which financiers “become” industrialists? Well, if we look at all the components of asset managers discussed above, we can see their length and depth of reach has led them to have important stakes in the entire economy. However, they aren’t passive owners, in fact it’s quite the opposite. Because the B3 has large permanent stakes in companies, they become more directly involved in the corporate boardroom, particular through their stewardship divisions. They engage with company management and help to influence corporate decision making. Asset managers and corporate managers will work behind the scenes to discuss and alleviate any concerns investors may have. Even if asset managers rarely vote against managers, this is not because they don’t have power over managers. In fact, when push comes to shove, they will resort to using voting power, as happened in the high level case of Exxonn in 2022 in a proxy war on corporate board composition. Rather, back-door relations often make using voting power unnecessary.

Understanding finance in the capitalist system

In short, Maher and Aquanno help bring readers to not only see finance’s historical role in capitalism, but its centrality. They also ask the question of what to do about it. Now that we know we live under the reign of large, powerful and influential financiers who are steering the movement of capital in a way we’ve never seen before, what does this mean for radical politics? What is above all emphasized is that the essential problem is capitalism, not just “finance”. Finance is merely a form of expression of the essential relation of exploitation that needs to be overcome in our communities and across the globe. The first step to any successful political project is to understand the world to then change it. Finance and industry are inseparable, and thus, our enemies are all components of the capitalist class. There is no chance of a class-compromise or détente with industry versus finance, because that is a misunderstanding of the relation between parts of the capitalist class itself.

Rather, we need movements that harness the power of the working class against the whole capitalist class. Maher and Aquanno strongly reject any social democratic project based on the idea of a coalition between industrial capital and the working class. Attempting to use the current structures of finance, rather than building a broader political movement to capture political power, is doomed from the start. Any radical movement must employ an understanding of the real dynamics of politics and the economy, and that includes how the state, capital and working class are presently organized. If this books helps us to know the world, our next task is to think about how to change it.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate