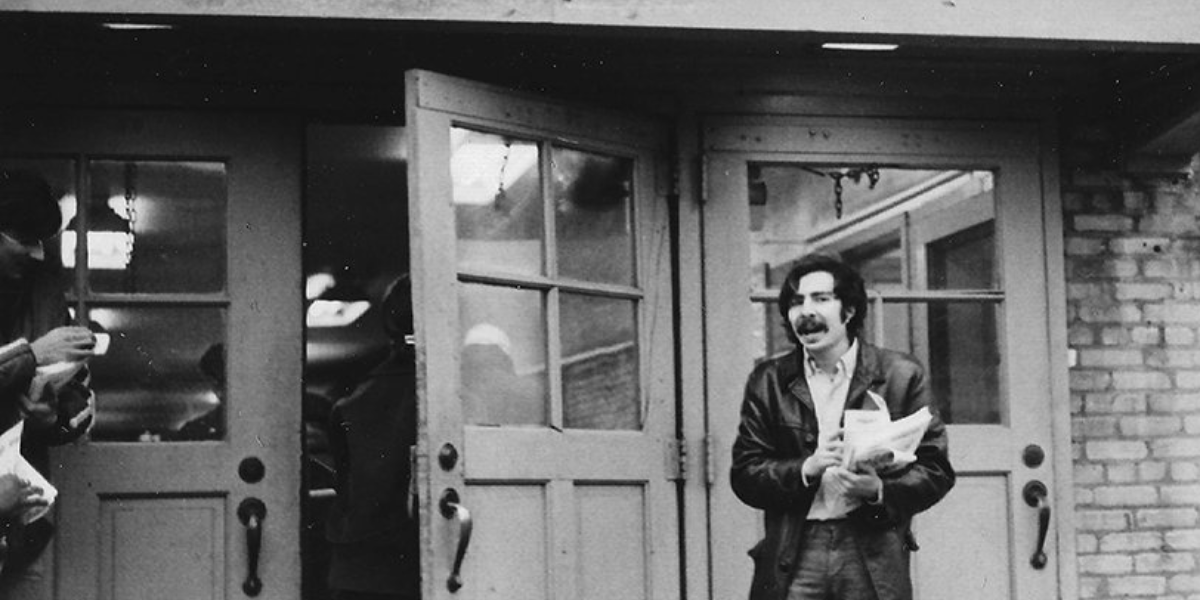

Fighting Times: Organizing on the Front Lines of the Class War by Jon Melrod (PM Press, 2022).

Jon Melrod’s Fighting Times: Organizing on the Front Lines of the Class War is an incredible contribution to documenting and generalizing the lessons of class struggle in recent history. Melrod was raised as the son of a lawyer in Washington, DC. As a rebellious teen he was drawn to radical politics in the 60s, organizing others at his all-boys boarding school to protest the war in Vietnam and writing to Mao Zedong asking for information on the Communist Party. After graduating from high school in 1968, he sought out the most radical, left-wing campus he could find, enrolling in the University of Wisconsin at Madison. It was a key hub for Students for a Democratic Society, the radical student movement that had over 100,000 members at the height of its power.

Melrod quickly threw himself into student politics and helped build the anti-war movement and built connections with the Black Panther Party. His organizing earned him close-watch from the police and a spot on an FBI watchlist. There were nights where he was followed home and he also faced intense police harassment. Through his activism, Melrod was drawn to politics of the Revolutionary Union (RU), eventually joining the socialist organization that centered the importance of the working class as key in the transformation of society.

Fighting Times documents the author’s life after graduation. In 1972, he left the campus for the factory. Believing that his role as a revolutionary was to be in the industrial working class, helping to spread socialist ideas and organize other industrial workers, he and other members of the RU looked for jobs, any jobs, in the factories of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Melrod worked a number of dangerous, non-unionized jobs before he was hired at American Motor Company (AMC), a unionized plant with the United Auto Workers (UAW). The bulk of the book details his experiences there. After his 6 month probationary period, he used his politics to do everything he could to increase the confidence and combativeness of his coworkers.

Being Jewish and an open communist, Melrod had to face down prejudice and red-baiting to help organize his coworkers to successfully beat back forced overtime and production speed ups. He did it by meeting his fellow workers where they were at. He found points of unity that brought people together, using issues his coworkers raised to bring people from diverse backgrounds together socially to find common ground. Once they had a basis of unity, Melrodwould then ask what could be done and take input from others and help shape a common fightback. This little group would become the basis of the Fight Back Caucus, a small rank and file group that could take independent action from the union and push a set of politics and expand the reach of those politics. The Fight Back Caucus used their brand of journalism, reports and letters written by workers from the shop floor, on regularly-printed leaflets to organize coworkers around class struggle and rebuild a fighting tradition in the union which was known in the 1930s for sitdown strikes that inspired the nation.

Often they would start small with a sticker that could be plastered around the factory, after that moving to buttons or a t-shirt. At each point he and his group of allies would assess how their message was resonating and use that feedback to inform next steps. Distributing leaflets, buttons and stickers allowed them to show their power and see who their audience was. This helped them find others who could be counted on to take collective action. This method helped them build majorities on the line who would refuse to do what the bosses said when it violated their collective agreement and essentially challenge who ran the plant. His successful campaign against speedups found him and another coworker Al Guzman wrongfully fired. They campaigned hard to win the membership to a solidarity strike for reinstatement. They would have been successful, but the union leadership purposefully miscounted the votes and the two were fired.

After more than three years, the National Labor Relations Board would force the company to rehire them with back pay, but in the meantime, Melrod had to find other work. A task made very difficult by a police force that would tail him wherever he went and would inform bosses and coworkers that he was a communist Black Panther. However, he managed to get a job at a non-union leather tannery. While there, Melrod relied on the support of his fellow Revolutionary Union members and sold their newspaper to other workers and helped lead campaigns against police brutality in his local community. After bouncing around a few jobs based on his organizing and police or FBI intervention against him, the author found a job at a plant that made steel tanks. As a Steelworker he quickly set about mobilizing his coworkers to assert their power on the factory floor while remaining principally anti-racist and anti-sexist.

Melrod demonstrates a class struggle politics informed by his membership in a revolutionary socialist organization. He demonstrates their worth over and over again as his determined fight against oppression had the effect of strengthening rank and file worker power and vice versa. His support for Menominee Land Defenders against police and vigilante violence helped strengthen his work in the steel tank factory. By patiently working to unite his coworkers to overcome racial division, incorporating them into a fight, Jon Melrod was able to overcome a complacent union leadership, rallying the rank and file to force a strike that won them substantial gains in the face of the inflation of 1975.

January 1976, Jon Melrod and Al Guzman were back with AMC and went right back to work building power as a revolutionary Autoworker. Against plant closures, Nazi coworkers, antisemitism, red-baiting, and an uncooperative local and national union leadership, the author used small caucuses and leaflets and newspapers to amplify class struggle messages and create a wider audience for those ideas. In doing so, he was able to play a part in wildcat strikes, organizing fellow autoworkers to oppose imperialism and march against the Ku Klux Klan, winning more power and security for women and black workers, holding racist and sexist managers and stewards accountable, and winning the best contract of any workers in the sector.

His determined organizing helped him and others in UAW form a United Workers Caucus and eventually win positions as stewards, chief stewards, and later president of the local, while the aggressive journalism of the caucus newspaper Fighting Times was put on trial for defamation. Despite a hostile judge and the backing of AMC, who had urged plaintiffs to bring forward the case, Melrod and his co-defendants won big. The shop floor, small-scale activism informed by the revolutionary politics that Melrod had employed wherever he went, was vindicated in court and had proven its power to the entire city and beyond, as the case was covered across the globe. And in the words of one juror “the paper is a necessary item in the factory to wake up the company to things that are happening.”

This book is an amazing example of the kind of strategies detailed in manuals like Secrets of A Successful Organizer and a living embodiment of the politics of The Rank and File Strategy, demonstrating the way in which a small group of determined workers can defeat the bosses and overcome the reluctance of labour leaders. It is a short, powerful and lesson-rich work that should be read by anyone interested in building power in their workplace.

To learn more about organizing on the shop floor, join us for our Secrets of A Successful Organizer book club organized by the Spring Labour Caucus.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate