July 7 marks 30 years since the Ontario NDP government passed the Social Contract Act (Bill 48), rewriting collective agreements and forcing massive concessions on public sector workers. For a generation of trade union activists, the Social Contract came to symbolize all that was wrong with the New Democratic Party.

The unexpected NDP win

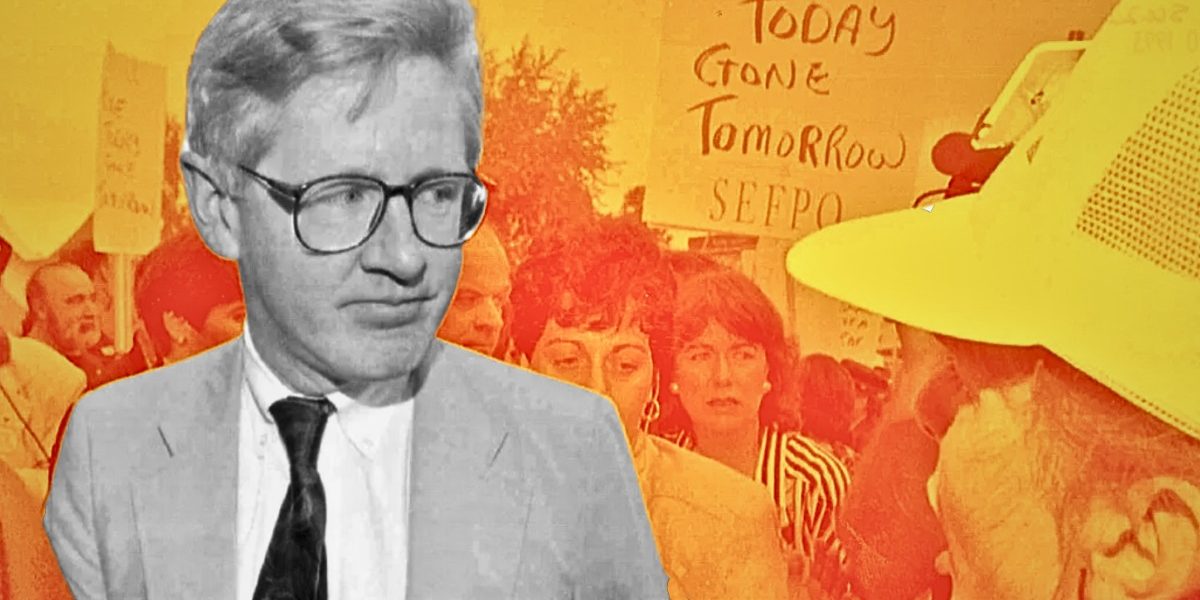

The election of the NDP in 1990 came as a surprise to not only most pollsters and pundits, but to the NDP and its leader as well. Bob Rae, won the leadership of the Ontario NDP in 1982 after serving as an NDP MP. His youthful appearance and media savvy won him the backing of both party and labour leaders.

The NDP under Rae had fought two elections, winning the balance of power in 1985 and losing seats to Peterson’s Liberals in 1987. By all accounts the 1990 election was supposed to be a clean sweep for Peterson’s Liberals. Rae thought this was probably his last election as leader.

Both the NDP and Progressive Conservatives, under their newly elected leader Mike Harris, ran campaigns focused on Peterson’s credibility gap. The NDP’s platform, the Agenda for the People, was released late in the campaign and was scant on details. It promised higher corporate taxes, higher social assistance rates, bringing in public auto-insurance, increasing the minimum wage to $7.20, and strengthening the Employment Insurance Act.

The 1990 election was a referendum on Peterson’s Liberals. The NDP surge in the election came late, with polls only indicating a possible NDP win days before the election. On election day the NDP won 74 seats with just 37 percent of the vote – a stunning majority.

Staring down a recession

By the fall of 1990, it was clear Ontario was entering into a recession. The early 90s recession was global but it hit Canada and Ontario particularly hard. One of the reasons Peterson had called an election early in his mandate was because the governing Liberals assumed the economy was headed for dire straits. Better to call an early election with high poll numbers than call an election in the middle of an economic downturn was the thought.

While this strategic choice didn’t pan out for Peterson, it did leave the NDP in charge just when a recession was taking hold. In the first year of the recession, 250,000 Ontarians lost their jobs. The first budget projected about a $10 billion deficit, about a three fold increase from the previous year. But almost all of that was because of the recession. The 1991 budget contained only about $350 million in new program spending – a paltry sum compared to the $53 billion for the total budget. There were also some new tax increases for upper income earners, but this was hardly an ambitious social democratic budget.

The media and the political right made fodder out of the ballooning budget. The NDP was painted as incompetent spendthrifts. The truth is while the deficit increased, Ontario’s debt to GDP ratio remained well within bounds of other advanced capitalist economies. The attack from the media and the right, however, served to increase the NDP government’s existing fear of being perceived as bad economic stewards.

Public auto-insurance put on ice

One of the biggest issues that the NDP had advocated for throughout the 1980s was the implementation of public auto-insurance. Other provinces, like Manitoba, Saskatchewan Quebec and B.C., had brought in no fault public auto-insurance. The NDP had promised to do the same in Ontario in its first term.

The insurance industry organized to resist this move. While Rae delayed, the insurance companies launched a public campaign to pressure the government to back down from the planned reform. Companies argued a move to a public system would cost thousands of jobs in the industry. The insurance industry mobilized their largely female workforce whose jobs they said were on the chopping block. Ministers and other high profile NDPers were subject to protests by women insurance workers (organized by the insurance industry). The industry also pushed an aggressive media campaign to force the government to back down.

By September 1991, Rae and the NDP backed down on bringing in public auto-insurance. This about face on a central NDP issue and campaign promise not only demoralized NDP voters, it also left the impression for all Ontarians the NDP was quick to abandon its promises.

Labour, the left and the NDP

The single most important piece of legislation that the Rae government passed was Bill 40, which brought in a series of sweeping labour law reforms. Bill 40 banned the use of scab labour by employers, brought in card check certification which made it easier to join a union, implemented successor rights, gave greater access to private property for picketing, and made it easier for workers to achieve a first contract.

The bill was fiercely resisted by the Coalition to Keep Ontario Working, the big business lobby group. KOW commissioned a study based on a survey of CEOs that claimed over 295,000 jobs would be lost as a result of the Bill 40. Another study claimed 450,000 jobs would be lost. KOW used public hearings on the bill to push its fear mongering about stronger rights for workers. Throughout the process, the newspapers sided with the big business lobby. Not surprising since just months earlier, the Toronto Star had used scab labour in a dispute with striking workers.

Bill 40 passed in late 1992 and went into force on January 1, 1993. This represented the upper limit of what workers achieved under an Ontario NDP government.

Deficit mania

In its first two years of power, the NDP had brought in important labour law changes, raised the minimum wage, raised welfare rates, invested in housing, and raised taxes on higher income earners.

At the same time, the government was laying the groundwork for severe austerity. In January 1992, Rae took to television to tell Ontarians there were unsustainable deficits ahead and action needed to be taken. The NDP’s main focus was to get the deficit under control.

Either the NDP was going to push forward real substantive changes to how the economy works and for whom, or it was going to appease the economic forces in power. Rather than take on the big business agenda head-on, the NDP in government was pulled into managing the economy. And, first and foremost, this meant placating business interests and creating a stable climate for investment and business.

It should be noted that much of the hew and cry about the deficit and impending debt wall was baseless. The government claimed that the deficit would be $18 billion by 1995, an over-the-top projection. The real figure was almost half of that. Ontario still had access to financial markets; there was little concern about its long run debt to GDP ratio.

The NDP was viciously attacked by the rightwing and under siege from the big business lobby but there is little to suggest that Ontario was facing an actual fiscal crisis. The net debt-to-GDP ratio under the Rae government was lower than any subsequent government in Ontario.

To get the deficit under control, the NDP opted to not go after the rich and powerful. Both a wealth tax and an inheritance tax were dismissed early on. The NDP was also not going to substantially raise corporate taxes. The government was more comfortable bailing out corporations, opening casinos, and doing big pharmaceutical companies favours, at the taxpayers’ expense.

Rae Days

For Rae and the NDP addressing the deficit was about showing it could play hardball with its own base. Rae used his regular meetings with union leaders to signal that he wanted concessions from unions. The NDP plan was to have general tax increases of $2 billion (a large portion of which fell on middle income earners and excluded corporations); make public program cuts of $2 billion (in addition to the $2 billion in cuts already announced); and wrest concessions from union members of $2 billion. Rae used the metaphor of a three legged stool to describe this corporatist model of cutbacks.

Some unions were willing to strike sector based social accords that encompassed early retirements, hiring freezes and even wage freezes. But Rae had other ideas. On March 30 1993, he publicly threatened public sector unions that they had to agree to wage rollbacks and mandatory days off, or face massive layoffs. He then unilaterally announced the suspension of public sector collective agreement negotiations. Negotiations between public sector unions and the government over the Social Contract began on April 5 under a cloud of animosity and distrust.

The government landed on a position forcing unpaid days off on public sector workers, excluding workers who were making less than $30,000 a year. The government wanted the unions to acquiesce to the opening up of 2500 collective agreements to accept massive concessions for about 950,000 workers. The NDP wanted to impose these concessions through sectoral bargaining tables. The unions, fearful of the unprecedented nature of the concessions and rewriting of collective agreements, refused. The NDP was trying to drive a wedge between the unions, by offering EI top ups to unions that voluntarily accepted the Social Contract and punishing unions that refused by denying access to the top up.

Unable to win unions over to voluntarily accepting massive concessions, the NDP legislated the Social Contract via Bill 48. Rae had promised the unions early on it would not legislate the Social Contract concessions. This was one of the single largest wage rollbacks in Ontario’s history.

The fallout was immediate and long lasting. Julie Davis, President of the Ontario NDP resigned immediately. NDP MPPs Karen Haslam, Peter Kormos and Mark Morrow, along with former New Democrat Dennis Drainville all voted against the legislation. Haslam also quit cabinet.

Amongst public sector union members, the imposed 12 unpaid days off became known as Rae Days. The Social Contract never went far enough to appease the NDP’s rightwing critics, but it did alienate its base. Most notably the Social Contract split the labour movement.

Labour divided

A month after the passing of the Social Contract, leaders from the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) voted to dramatically curb its financial support of the Ontario NDP. CUPE would have a similar discussion about pulling its support in the fall, landing on offering qualified support. Most private sector unions, minus the CAW, ended up supporting the NDP – reasoning that taking concessions to preserve jobs was the norm in the private sector.

At the November 1993, Ontario Federation of Labour convention the split became open. A motion by the executive board to disaffiliate from the NDP provoked a walkout from delegates from the United Steelworker, the International Association of Machinists, the United Food and Commercial Workers, and the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers. These unions circulated a statement on pink paper to delegates prior to their walkout which argued that the NDP had brought forward good pieces of legislation and needed to be supported by unions. The walkout caused the OFL to lose quorum. Public sector unions who criticized the NDP were looking to shift more of their resources away from the NDP and towards building movements.

The split between “pink paper unions” and the public sector unions (plus CAW) meant the labour movement was disastrously divided.

In 1995, Mike Harris was swept to power on a mandate to cut public services and attack workers. The split in the union movement played out in how the unions sought to combat Harris. At the 1995 OFL convention, the pink paper unions sought to push an electoral strategy while the CAW and the public sector unions pushed a series of one-day general strikes. While a compromise was reached that pushed both strategies the divisions inside the labour movement only deepened. Despite organizing massive protests and strikes against Harris, the union movement remained divided. This acrimony and division over the NDP played a role in weakening the ongoing resistance to Harris.

The NDP’s attack on collective bargaining paved the way for unions like the CAW to adopt strategic voting. If there was no difference between the Liberals and NDP then why not deal with both was the reasoning. The divisions over the NDP in the labour movement in Ontario are still at play today.

Learning from Rae days

Thirty years later, what can we learn from the Social Contract debacle?

First it is important to understand that the NDP’s assault on unionized workers can not be chalked up to bad leadership. While Bob Rae later drifted away from the NDP into the Liberal Party, dismissing the Social Contract as a product of Rae’s leadership clouds rather than clarifies the truth. Rae had the support of almost his entire caucus in imposing the Social Contract. His Minister of Finance, Floyd Laughren, was on the left-wing of the party.

The NDP was also not forced into making such a choice because of the bad economy. The recession was deep and limiting for the Rae government, but the NDP had other options. They chose the option that pushed the pain of the recession onto the back of workers.

The reality is the NDP in power will invariably be pushed into managing the economy. Unless there is an alternative vision of how to organize the economy and a corresponding strategy about how to achieve it, the NDP and other social democratic governments will be forced to facilitate the smooth operation of capitalism. The NDP could have chosen to run more deficits and implemented a robust wealth tax, but that would require a massive confrontation with capital, which the NDP was not prepared to do.

The left and labour movement under the Ontario NDP government was too quiet and focused on backroom deals. If the NDP in power was going to deliver it needed to be pushed by strong social movements. The reality was that the greatest counter pressure on the NDP was the big business lobby.

The legacy of the Social Contract for many in the labour movement is one of betrayal. The NDP sold out its union base to appease capital – pleasing no one in the process. If the NDP is ever elected again in Ontario, unions and social movements should learn that class war won’t diminish, it will intensify. And the only way to advance our interests is to organize strong movements outside the legislature, not bank on the people sitting inside it.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate