GardaWorld is an odious enterprise that profits from armed conflict, deportations and right-wing fear mongering. The Montréal firm’s government and military ties say a great deal about the Canadian establishment.

Collaborating with Trump and ICE in the US

Garda’s US subsidiary has a USD $8 million contract to provide armed guards to oversee ‘Alligator Alcatraz,’ a controversial detention facility in South Florida recently established to imprison migrants. It is located in an area swarming with dangerous habitat as part of a malignant security/public relations strategy. Garda’s US subsidiary reportedly donated $5,000 to Florida governor Ron Desantis.

Garda’s role at ‘Alligator Alcatraz’ is but one example of the company’s many ties to the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency. The world’s largest privately held security company has been criticized for rights abuses at migrant facilities in Texas, Chicago and elsewhere.

Garda benefits from these repressive border and political policies. CEO Stephan Crétier has talked openly about the company’s need for repressive university, business and political leaders and the company has long sought to “convince different levels of government to increase their use of the private sector in public safety.”

The child of neoliberal militarism

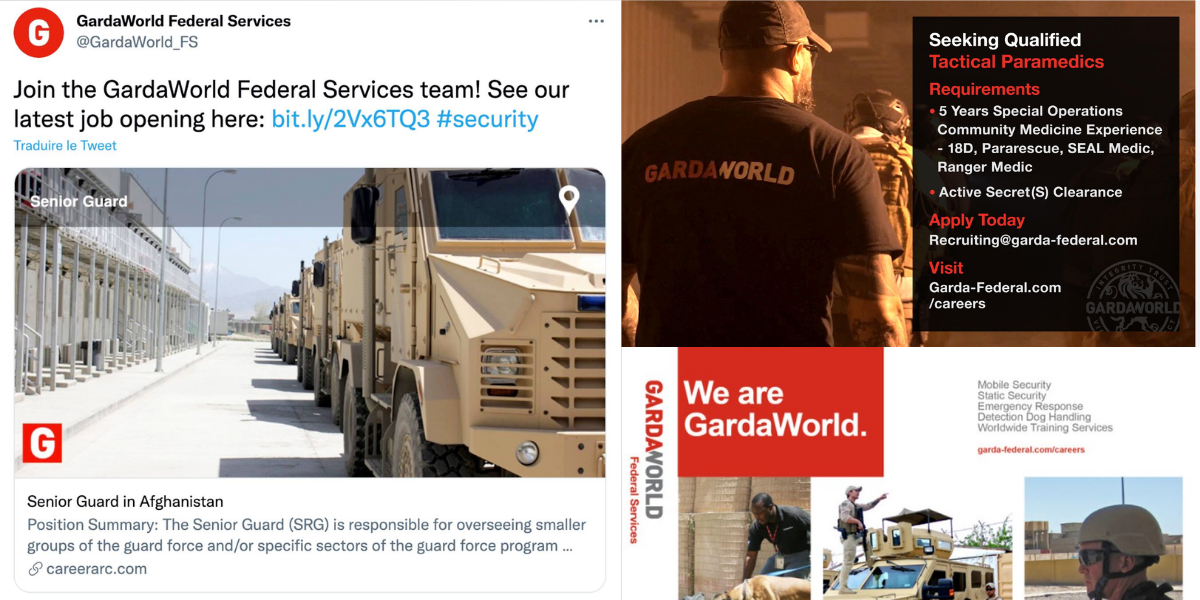

While Garda is a creature of neoliberal capitalism, it’s also a creature of NATO and US aggression. With 120,000 employees worldwide, Garda has been dubbed “Canada’s Blackwater”. A 2014 Canadian Business profile described Garda’s business as “renting out bands of armed men to protect clients working in some of the Earth’s most dangerous outposts.” Garda has operated in over 35 countries including Iraq, Afghanistan, Colombia, Pakistan, Nigeria, Algeria, Yemen, Somalia and Libya.

Established in 1995, the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq in the early 2000s propelled Garda’s international growth. Iraq represented nearly a quarter of its $683 million in revenue in 2006. In 2007 four Garda employees were kidnapped in Iraq. They were later killed.

Garda was engulfed in controversial and violent incidents in Afghanistan as well. In 2012 two of its employees were caught with dozens of unlicensed AK-47 rifles and jailed for three months. Again in 2014, its head in Afghanistan was jailed for allegedly smuggling guns. In 2019, three children were among a dozen killed when a minibus full of explosives crashed into a Garda SUV carrying foreign nationals in Kabul. That same year, the Taliban attacked the complex where Garda’s offices were located in an incident that left thirty dead. The Kathmandu Post reported that Garda illegally shortchanged the family of a Nepalese employee killed in the attack.

Garda’s most controversial foray abroad is in Libya. Sometime in the “summer of 2011”, according to its website, Garda began operating in the country.

Garda in Libya

After Libya’s National Transition Council captured Tripoli (six weeks before Muammar Gaddafi was killed in Sirte on October 20, 2011) the rebels requested Garda’s assistance in bringing their forces “besieging the pro-Qaddafi stronghold of Sirte to hospitals in Misrata”, reported Bloomberg. Garda’s involvement in Libya may have contravened that country’s laws as well as UN resolutions 1970 and 1973, which the Security Council passed amidst the uprising against Gaddafi’s four-decade rule. Resolution 1970 mandated all UN member states “to prevent the provision of armed mercenary personnel” into Libya while Resolution 1973 mentioned “armed mercenary personnel” in three different contexts. In an article titled “Mercenaries in Libya: Ramifications of the Treatment of ‘Armed Mercenary Personnel’ under the Arms Embargo for Private Military Company Contractors,” Hin-Yan Liu pointed out that the Security Council’s “explicit use of the broader term ‘armed mercenary personnel’ is likely to include a significant category of contractors working for Private Military Companies.”

Still, contravening international law can be good for business. As the first Western security company officially operating in the country, Garda’s website described it as the “market leader in Libya” with “over 3,500 staff providing protection, training and crisis response.”

Garda’s small army won a slew of lucrative contracts in Libya. The Montréal company protected European Union Border Assistance Mission (EUBAM) personnel who trained and equipped Libyan border and coast guards in a bid to curtail African migrants from crossing the Mediterranean. Garda’s initial four-year EUBAM contract garnered attention in early 2014 when 19 cases of arms and ammunition destined for the company disappeared at the Tripoli airport. But the company didn’t let this loss of weapons deter it from performing its duties. According to Intelligence Online, company officials asked, “to borrow British weapons to ensure the safety of EU personnel.” The request found favour since Garda already protected British interests in Libya, including Ambassador Dominic Asquith. In Under Fire: The Untold Story of the Attack in Benghazi, Fred Burton and Samuel M. Katz describe the ambassador’s protection detail: “Some members of Sir Dominic Asquith’s security detail were undoubtedly veterans of 22 Special Air Service, or SAS, Great Britain’s legendary commandos, whose motto is ‘Who Dares Wins.’ Others were members of the Royal Marines Special Boat Service, or SBS.”

In June 2012 a rebel group attacked Asquith’s convoy in Benghazi with a rocket-propelled grenade. “The RPG-7 warhead fell short of the ambassador’s vehicle”, notes Under Fire. Two Garda operatives “were seriously hurt by fragmentation when the blast and rocket punched out the windshield of the lead vehicle; their blood splattered throughout the vehicle’s interior and then onto the street.”

In 2023, seven Garda employees were reportedly detained in Libya for two months. There are few regulations constraining Canadian private security companies’ international operations. Unlike the US and South Africa, “Canada does not have legislation designed to regulate either the services provided by Canadian PMSCs [private military security companies] operating outside of Canada or the conduct of Canadian citizens working for foreign PMSCs.” Furthermore, Ottawa has not signed the international convention against the recruitment, use, financing, and training of mercenaries and has been little involved with the Human Rights Council’s Working Group on the use of mercenaries.

In 2022 the Quebec government invested $300 million in Garda. The Montréal firm also has substantial connections in military–political circles. The head of Garda’s Afghan operations, Daniel Ménard, previously commanded Canadian Forces operations in Afghanistan while Garda’s board has also included former minister Christian Paradis and ambassador to the US Derek Burney.

GardaWorld demonstrates the immorality of Canada’s rich and powerful and their corporations.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate