The People’s Republic of Walmart by Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski (Verso, 2019)

As COVID-19 engulfs the globe, the perpetual tension within capitalism between private profit and human need has risen fully into view. Why in the midst of a global pandemic, researchers and medical experts warned about for years, are there severe international shortages of test kits, basic medical supplies, infrastructure, and other essential items? Why have major pharmaceutical companies completely abdicated the field of research and development for vaccines, antivirals and antibiotics?

In short, why are we literally staking our lives on an economic system that is both structurally incapable and uninterested in meeting the major national and international challenges of the twenty first century?

The American historian Mike Davis wrote recently that in an era when “capitalist globalization seems to be biologically unsustainable,” the time is overripe for an independent socialist project advocating for broad social ownership and democratic control of economic power in society.

While the global crisis has led to some small concessions, such as minimal income maintenance programs, broad-based economic planning based on public need has been conspicuously left off the table by all major parties. Leigh Phillips and Michael Rozworski book People’s Republic of Wal-Mart is essential reading to help the left put democratic planning back on the agenda.

Utopias through the mist

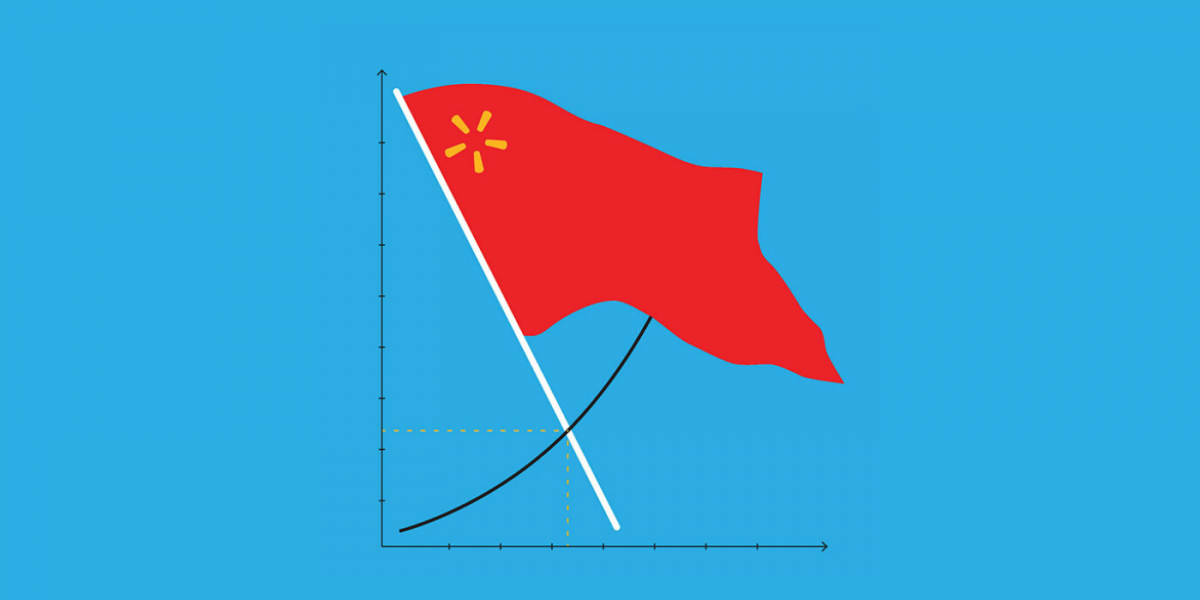

The authors’ central argument revolves around the conceit that while Wal-Mart (along with Amazon and other large multinationals) is a globe-spanning capitalist monolith par excellence, it is also an example of a vast, centrally planned enterprise that utilizes internal non-market allocation and distribution (i.e. planning) to great success.

Contrary to planning’s detractors, the authors contend that capitalism in the twenty first century is in fact dominated by large centrally planned firms (they note that Wal-Mart’s yearly revenue is equivalent to the entire economy of the USSR circa 1970!). In short, we already have planning and it works. This leads to the obvious question, if capitalists can utilize planning with such intricate, profit-seeking rigor, why can’t socialists do the same, but for public and egalitarian ends?

The question is more complicated than it sounds. Much of the first half of the book is dedicated to explaining the “socialist calculation debate” of the early twentieth century between Austrian and socialist economists. Most are familiar with the broad contours of this line of argument by way of the popular refrain that socialism will always fail because central planning is markedly inferior in its allocation and distribution of resources to a market-based system that utilizes the price system.

Friedrich Hayek, the Austrian economist often credited as the philosophical forerunner of neoliberalism, famously called prices a “system of telecommunications”. Hayek believed that prices under capitalism imparted vast stores of collective knowledge to producers, consumers, and everyone else in between that ensured the social coordination of the entire economy.

Without a price system or any workable alternative, Hayek argued, it would be impossible for a team of central planners to gather and process the necessary information in order to efficiently allocate the resources of an entire economy in real-time. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end-of-history triumph of neoliberal capitalism in the early 1990’s, the theoretical argument received what many considered empirical confirmation.

Yet despite capitalism’s ostensible triumph, the rise of ubiquitous mega-firms like Wal-Mart, Amazon and others – all of whom use extensive internal planning mechanisms rooted in “big data” — seems to offer a real life counterargument to the contention that planning is unworkable. Is not the rise of big data alongside advanced computing technology the modern advent of the “system of telecommunications” that Hayek saw as the critical role that prices played?

The authors explore in detail how Amazon uses big data to accurately and efficiently forecast, manage and distribute goods worldwide, from the moment a product enters their warehouse to the moment in lands on a consumer’s doorstep. Similarly, when peering into the blackbox of a firm like Wal-Mart, one sees a paragon of logistical efficiency, with innovative global supply chain management techniques rooted in algorithmic record keeping as well as cooperative planning with suppliers and distributors.

In contrast, the authors offer up the glaring counterexample of Sears, whom under the recent tutelage of a right-wing Ayn Rand-devotee CEO, instituted internal markets that divided their product divisions into as many as 40 competing enterprises. The results were disastrous, as each division fought relentlessly amongst the others for profitability, destroying the firm-wide cooperation and planning necessary for running a large enterprise.

Planning by and for whom?

If we accept the author’s contention that not only does planning work, but it is in fact already being used to great success on a wide scale, we’re still left with the fundamental question of what a system of public planning should look like on a large scale. On this question the authors are less clear.

Simplistic calls for nationalization of major industries or retailers that simply “lop off” the private owners at the top and replace them with a set of national administrators, while leaving the hierarchical, exploitative infrastructure intact is clearly insufficient, as acknowledged by the authors. The success of Wal-Mart and others is based not just on its use of efficient internal planning but also its super-exploitation of labor in developing countries overseas, while paying poverty wages to its non-unionized, precarious employees at home.

This basic point was made over 120 years ago by Irish socialist James Connolly who noted that: “state ownership and control is not necessarily socialism – if it were, then the Army, the Navy, the Police, the Judges, the Gaolers, the Informers, and the Hangmen, all would all be Socialist functionaries.”

It’s clear that any socialist alternative worth its name requires that economic planning incorporate broad democratic ownership that overturns the fundamental social relationship between capital and labor — from a relationship of tyranny and oppression to one approaching some level of democracy and workers’ self-rule.

In addition to its emancipatory effects, the authors argue that internal democracy is necessary to the overall effectiveness and vitality of planning institutions. They take pains to explore the ways in which nationalization without internal democracy as well as meaningful public accountability (in the cases of the UK’s National Health Service and planning under the Soviet Union) led to the deformation of these institutions as well as the creeping rot of marketization and hijacking by rapacious private actors.

These concerns are doubly important when one considers the issues of privacy and freedom in the age of big data: the replacement of unaccountable Silicon Valley oligarchs by a similarly unaccountable set of technocrats is cold comfort for those who seek a free and democratic society.

The Wal-Marts and Amazons of our time are archetypes of twenty first century capitalism that inspire awe as feats of vast social coordination and data-based logistical efficiency, as well as terror at their rigorous exploitation of labor and the environment in the service of enriching a privileged few.

In building a socialist project seeking to wrest back a vision of human liberation from the clutches of private domination, one must keep both sides of this coin in full view. Broad economic planning based on public need is possible, but it will require democratic social ownership if it is to be emancipatory in more than name only.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate