Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, decades of cuts to social assistance and the gutting of social programs by successive governments led many to look to a form of basic income as a solution. But in the wake of a global pandemic and severe economic crisis, basic income policies have garnered renewed interest. It is not hard to understand why: the appeal of a basic income is its appearance of addressing inequality, poverty wages, lack of income supports and a broken welfare state. In this regard basic income has a lot in common with an idea and movement that swept across much of Western Canada in the 1930s, social credit.

The Social Credit theory

The idea of social credit was the brainchild of British engineer C. H. Douglas who had developed the economic theory during World War One and took to popularizing it during the 1920s. Douglas argued that the financial system generated an artificial scarcity of both producer and consumer credit. This scarcity of credit was leveraged by the private banks due to their monopoly on credit-creation.

In the social credit economic worldview the land, labour, machinery and raw materials that made up the useful productive power of the economy was real credit. Money was supposed to reflect the value of real credit, but the financial powers used their monopoly power to restrict credit in order to boost their profits. This limitation of credit within the system lowered purchasing power which made it harder for consumers and independent producers to access needed materials and goods to thrive. Social credit saw this restriction of credit as an inefficiency within the capitalist financial system. In this view the free market was not causing economic hardships, rather it was being distorted by the power of financial capital and the result was a failure to provide people with enough purchasing power for them to enjoy the fruits of society’s economic production.

The solution to this problem was the creation of a National Credit Office which would issue credit to consumers, a national dividend, to ensure effective demand within the system. Douglas and social credit theory abhorred the idea of using the state to expand public services, the social safety net or to address unemployment.

Farmer-settler contradictions and the rise of Social Credit

Social credit began to gain widespread popularity in the 1930s, especially in Western Canada amongst farmers. Since the start of the “wheat boom” of the late 1890s over a million people moved to the Prairies as part of the white settler-colonial project of the Canadian state. The construction of a transcontinental railway, and the doling out of land to white homesteaders, part of the “National Policy” helped to facilitate this economic boom. As a result population density increased and wheat production doubled in the span of two decades.

As J.F. Conway explains farmers-settlers were “small-capitalists who embraced private enterprise, individualism, hard work, and entrepreneurial ability. They were a key element in the nation-building capitalist project embodied in the National Policy.”

While farmers in essence embodied the capitalist ethos, their material reality quickly bumped up against the reality of the free market. Farmers found themselves on the wrong end of the capitalist stick, at the mercy of capitalist manufacturers, transport companies, and banks who used their effective monopoly position vis a vis the farmers to inflate prices. On top of that tariff policies for manufactured goods added to the burden placed on farmers. The only way for farmers to survive was to expand and intensify their production.

But expanding their land and upgrading their farm equipment meant taking on increasing debt loads. The experience of most farmers was one of crippling debts and economic insecurity. While many retained the ethos of small commodity producers and attachment to private property, the market pushed many to look for collective political solutions. The agrarian populist movement of the first two decades of the 20th century resulted in significant reforms like the Canadian Wheat Board and culminated in farmer-backed political organizations winning provincial elections in Ontario, Alberta and Manitoba, while also having a strong showing in the 1921 federal election.

But a steep decline in wheat prices in the early 1920s, combined with political setbacks, fractured the populist movement. The federal Progressive Party was split on how to orient to the Liberal government in opposition. At the provincial level newly elected farmer-backed parties were directionless and quickly alienated their base. Even hard won reforms like the wheat board were rolled back. In this political vacuum a number of organizations and ideas stepped in to compete for farmer’s loyalty.

The onset of the depression exacerbated the precarious economic situation that farmers found themselves in. By the early 1930s farmers were looking for alternatives. In Saskatchewan this came in the form of support for the nascent Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), while in Alberta the newly formed Social Credit Party of Alberta was swept into power in 1935.

Social Credit in power

In the early 1930s William Aberhart, a part-time school teacher and radio host, took to proselytizing the ideas of social credit. He blended a powerful call for monetary reform with conservative Christian rhetoric. His ideas split the United Farmers of Alberta, and eventually led to the formation of a Socialist Credit Party of Alberta. The promise of a national divided for all and the rhetoric of putting banks in their place proved highly popular with voters in Alberta, and it also put the CCF on their heels.

Aberhart and the social credit movement looked to quickly make inroads in other provinces, especially neighbouring Saskatchewan. CCF leadership in Saskatchewan responded by pointing out the rhetoric of social credit promises could not match its reality under capitalism; it was an illusion to preserve capitalism. George Hara Williams, a leading figure in the CCF in Saskatchewan noted that the type of society social credit promised required the socialization of wealth, not individual dividends. While most of the CCF leadership opposed the social credit, Tommy Douglas initially pursued an accommodationist approach, by accepting the Social Credit Party nomination in the 1935 federal election. This popular front approach of unity at all costs against the Liberals was pursued by both the Communist Party and some sections of the CCF.

But it was clear that by 1937 Social Credit’s promise of reform was running out of steam. C. H. Douglas, the founder of social credit, was brought into the Alberta government as advisor, but resigned in 1937 demoralized by the government’s inability to deliver on its promises. As Douglas stated at the time, “to the extent that ʻSocial Credit has failed in Albertaʼ, i.e. has not been tried, the root cause has always been evident – a persistent determination not to recognize that when Mr. Aberhart won his first electoral victory, all he did was to recruit an army for a war. That war has not been fought.”

Promise and reality

There was good reason for Douglas to be crestfallen about the Social Credit government in Alberta. After passing almost no reforms in its first year in office, in 1936 Aberhart’s government circulated a Covenant for citizens to sign in order to usher in social credit. This covenant promised that all citizens would receive a type of guaranteed income above and beyond whatever wages they were already earning. Aberhart promised every citizen over 21 years of age would get a monthly dividend of $25, and those under 21 would also receive a smaller monthly amount.

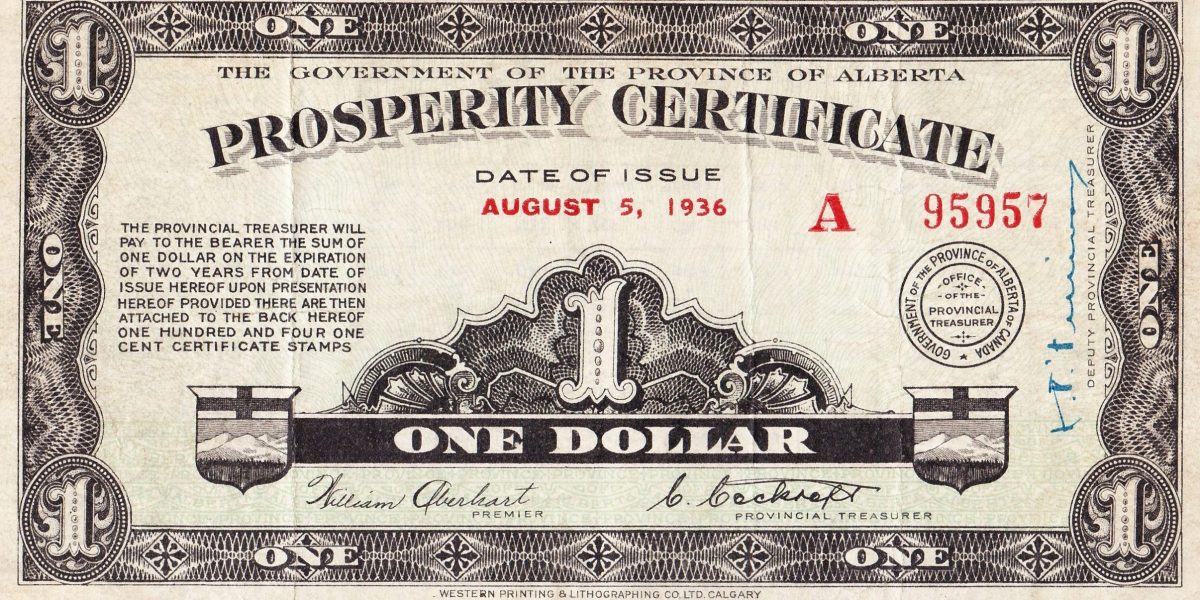

But the money never materialized. Facing a fiscal crisis, with nearly half of all revenue going to service the debt, Alberta defaulted on a major bond and cut interest rates on public debt. The guaranteed income, in the form of a dividend, was paid out in special prosperity certificates to citizens which supposedly backed Alberta’s credit. The government pushed hard for citizens to use the new scrip for all transactions. But the government itself refused to take the prosperity certificates as a form of payment. After printing and circulating a quarter million in new scrip it became obvious that the certificates were not circulating.

After the blunder of the prosperity certificates and facing internal criticism from other social credit supporters, Aberhart’s government passed the Alberta Credit House Act. This promised to provide cheap credit to all, a house for every worker, a business for every entrepreneur and economic independence for all. The act was a clear violation of the federal powers over banking and currency. Aberhart’s government used the promises contained in the Alberta Credit House Act to boost its popularity, despite never taking any concrete efforts to make it a reality.

By 1937 dissension in the Social Credit Party ranks began to grow. Aberhart was being publicly criticized by Douglas, while backbencher grumbling about the lack of social credit policies being implemented grew into an open revolt. In response Aberhart agreed to try again to pass legislation asserting provincial power over the banking system. This turned out to be the last gasp of social credit monetary policy. All three pieces of legislation were struck down. The Social Credit Party of Alberta won re-election with a reduced majority in 1940. But by this time the party had all but abandoned the tenets of social credit monetary policy as unworkable. Instead they focused on populist conservative measures mixed with conservative christian rhetoric. The death of Aberhart in 1943 and the ascendancy of Ernest Manning to premier cemented this direction.

Social credit parties existed in every province, some drawing significant votes through the 1940s and 1950s. In British Columbia, the Social Credit Party won election in 1952 and dominated provincial politics until 1991, winning every election except for 1972. Learning from the Alberta failure in implementing an unworkable social credit monetary policy, it abandoned all pretence of instituting social credit before it assumed office.

Social credit quickly became a bastion for right-wing social conservative politics across the country and remained so through the 1990s, but this was not its origin. The initial social base of social credit were farmers who embodied a capitalist ethos but were forced into conflict with aspects of the capitalist system. The politics of farmers vacillated between supporting an agrarian populism of the left that argued for socialization of wealth, and of the right which supported monetary reform and freer markets. The economic turmoil heightened the political polarization and instability of the farming class, which was caught between workers and capitalists.

From Social Credit to Basic Income

It is easy to dismiss the ideas and experience of the social credit movement as a peculiar anomaly that reflected the social dislocation of the settler-colonial farming class. But the rise of social credit does have relevance for today. The quirky and muddled economic theories of social credit mirror the economic arguments underpinning basic income and Modern Monetary Theory.

Social credit reflected the populism of a class caught between capitalism and labour. It hoped to preserve the system but address the real material concerns of farmers. Its inability to achieve this outcome was not because of a lack of effort or political fortitude. Rather the economic promises of social credit were not compatible with capitalism. Social credit as an economic theory was based on a fallacy that capitalism could be fixed if only there was easy and universal access to credit to boost consumer demand.

Social credit’s populist appeal sought to position its idea beyond the left and right paradigm of Depression era politics. Farmers were facing real economic hardships and social credit seemed to offer a solution that appealed to their deep desire to address their material concerns and to their sensibilities as small commodity producers. But the social credit movement failed to patch up capitalism and in the process descended into a right-wing reactionary political force.

As with social credit, basic income elides class divisions and the nature of the capitalist state in favour of rosy visions of a future where everyone’s needs are provided through a guaranteed income. Basic income has a long history of being supported on both the left and right: both Martin Luther King and Milton Friedman supported some version of a basic income, the former as a part of a mechanism to abolish poverty, while the latter as means by which to destroy the welfare state. The fact that basic income could be supported from such divergent political perspectives speaks to the ambiguity and elasticity of basic income as an idea. It can be targeted or universal. It can replace existing social programs or supplement them. It can cost a few a billion dollars a year or hundreds of billions. It can usher in a whole new world of work and leisure or accelerate a failing social assistance system. Because it is a vague idea and policy, and most discussions leave it the realm of abstraction, it can mean almost anything to anyone.

But the very notion that the government will provide a robust Universal Basic Income (UBI) for all, while also maintaining private ownership over property and production is what Geroge Hua Williams called the “the last illusion of capitalism”. As Williams stated in 1935, “the Aberhart proposal is merely an attempt to patch up the present system and is based on fallacious economic reasoning.” Similarly, it is both economically and politically infeasible for a capitalist state to provide a UBI at high enough levels, to allow workers to sit outside the job market and still have their basic needs met.

This is why the illusions of UBI repeatedly crash up against reality. Over the last number of years, governments and NGOs in many regions ran pilot programs to test different versions of basic income. The wide ranging study by the Public Services International summarized the results of these experiments: “It could find no evidence to suggest that such a scheme could be sustained for all individuals in any country in the short, medium or longer term – or that this approach could achieve lasting improvements in wellbeing or equality.”

Beyond patching up the system

Basic incomes appeal is that it appears to offer a unique policy and political solution to decades of austerity and inequality. It has all the allure and trappings of a shortcut to better future. Advocates of basic income see it as an idea that is “neither left nor right, but forward.” While basic income has appeal across socio-ecomomic categories, some of its most ardent supporters come from the ranks of small business and the self-employed, who view a Universal Basic Income (UBI) as a wage top-up or as a way to encourage entrepreneurial activity. The populist appeal of basic income skirts over the material reality of instituting the policy or the dangers of the rightwing to use it to further erode social programs.

While many academics and basic income boosters look to the brief mincome experiment in Manitoba as an example of what a made-in-Canada basic income could be, the experience of social credit cannot be ignored. A UBI, with its questionable economic underpinnings and cross class appeal has many parallels with social credit. And like those on the left who criticized social credit in the 1930s it is incumbent upon us to understand the appeal and the contradictory nature of UBI, and to reach out to those who are drawn to it from the left while exposing those pushing it from the right. But rather than building cross-class illusions in a system that can’t be fixed, from social credit to basic income, we need to mobilize for solutions that empower workers to socialize wealth and to take over production.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate