The Filipino people are no strangers to mourning. Many Filipino migrant workers will tell you harrowing stories of personal grief, the kind of trauma that might make many of us retreat from the world for months or years.

A coworker used her minimum wage earnings to fly to the Philippines twice in two months in response to the unexpected deaths of her parents, one after the other. A friend had not seen her daughter for a decade, raising her child through nighttime phone calls. I met one worker who visited the Philippines for the first time in years for her son’s funeral and lost her immigration status upon her return to Canada.

Some years ago, I taught English to a Filipina domestic worker who worked 12-hour days while living in her employer’s house as a caregiver, gardener, chef, personal assistant, and cleaner. She carved out 4 hours every Tuesday evening to transit from a remote suburb outside of Toronto to our ESL classes, and she had spent over $900 on CELPIP tests in hopes of getting PR.

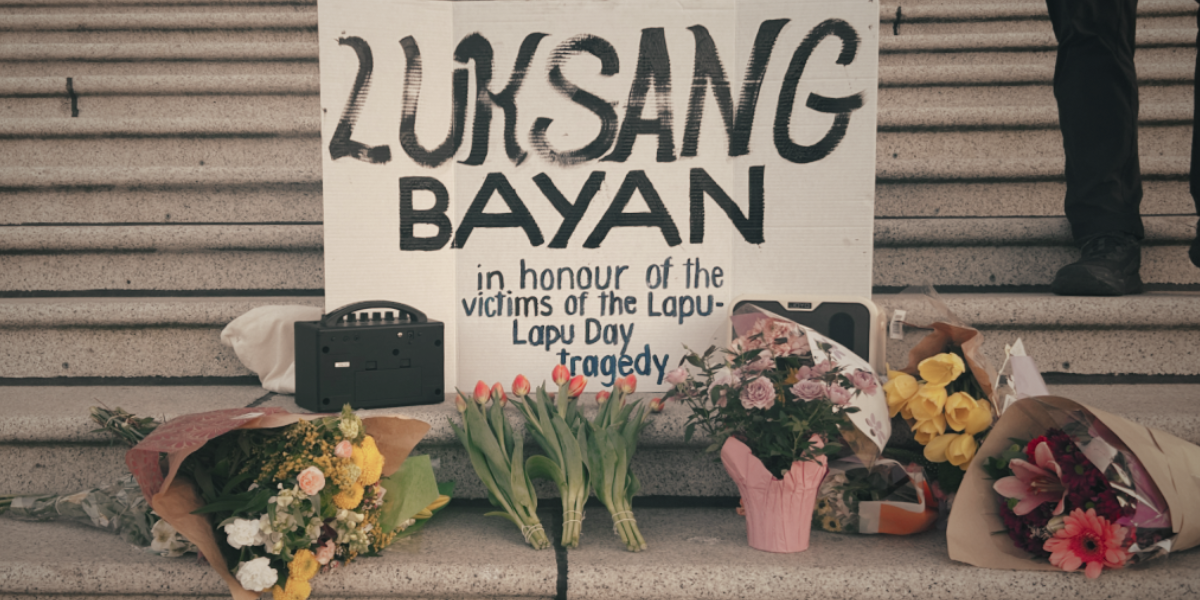

The car-ramming attack at Lapu-Lapu Day in Vancouver, BC, has brought Filipino grief into the spotlight. The media has focused on the contributions of the Filipino community to Canada: our good cheer, our peaceful nature, our generosity. Filipino people give and give, said BC premier David Eby in the wake of the tragedy.

Our people give, perhaps because we are kind and generous people—but also because circumstance has forced us into servitude. The colonial history of the Philippines has pushed our nation into abject poverty. The minimum wage in Manila is currently just over 530 Philippine pesos per day—around 13CAD. Over 7,000 Filipinos leave the country every day in search of better opportunities. We are vulnerable to exploitation and scams, like Mary Jane Veloso, who was imprisoned on death row in Indonesia for 14 years before being repatriated to the Philippines, where she remains in prison.

Why has the killing at Lapu-Lapu Day so deeply moved the Filipino community worldwide? It is, first and foremost, a tragedy of enormous consequence: 11 confirmed casualties, dozens of critical injuries, and hundreds of traumatized witnesses. Yet luksang bayan has made a space for us to grieve as a whole community—a global one. We are rocked not just by tragedy, but by the injustice of our visibility turning to vulnerability. For once, we were not caregivers and cleaners and agricultural workers, invisible to the bourgeois society that put us there. We were celebrants and heroes. And we became a target.

Lapu-Lapu is celebrated not just as a cultural figure but as an anticolonial hero. He famously defeated Portuguese explorer and colonizer Magellan in the 1521 Battle of Mactan. Certainly the tragedy at Lapu-Lapu Day was no battle. It was a massacre of families, beloved community members and friends. Yet it is our resistance that has brought some measure of healing to our people—not our generosity, our ability to accept difficult circumstances, our quietude in bowing down to our employers, but our demanding presence and public vigil. Our occupation of public space.

I reflect on the phrase luksang bayan. Luksa is mourning. Bayan means national—but in the sense of a people, not an abstract territorial boundary. Our people’s mourning, our public mourning. Across the country, community members have united to grieve openly in every city where Filipinos are found.

I moved from Vancouver to Calgary just a few weeks ago. Close friends in Vancouver shared with me their experience of witnessing the attack or responding in the aftermath. Many of my loved ones contributed to immediate crisis response and vigils. Participating in BAYAN Canada’s efforts to compile and amplify public vigils, both BAYAN-led and otherwise, has helped me to feel connected to my beloved community in Vancouver.

The Filipino people ourselves have responded to the call for a public space to grieve. As activities occur in places as far from Vancouver as Fredericton and Yellowknife, I have seen and felt firsthand the importance of a country-wide machinery to bring together these diverse initiatives.

On-the-ground responses have been coordinated by cultural groups, regional associations, churches, and grassroots organizations. BAYAN organizations are not present in every Canadian city, but BAYAN Canada has been able to quickly coordinate a large segment of the Filipino community and connect Filipinos in Canada with compatriots in other countries, including back home in the Philippines. Statements from international organizations and vigils in Seattle and Manila have shown the impact of an organization that can coordinate and build unity across sectors and places. When we unite as Filipinos in Canada, we strengthen our capacity to respond to crises quickly and effectively.

I reflect on our political choice to mourn in public and to lean on each other as the investigation into the attack continues. The motivations of the killer remain unconfirmed and will likely remain unknown for a long time. The true vulnerability came at the hands of the Vancouver Police Department and the City of Vancouver, who failed to implement basic security measures that are standard practice for other festivals.

Rather than focusing on questions of the killer’s individual mental health, mourners at public gatherings have highlighted the systemic issues that contributed to this tragedy, including calling for additional mental health support services. Vigils have brought messages of solidarity between communities, especially as more victims from non-Filipino backgrounds have been identified. Far from fomenting anger and discrimination against the killer on the basis of mental health or race, the Filipino community has united with all Canadians in genuine solidarity and grief.

As the police will likely take blatant advantage of this attack as an excuse to snap up more funding, let us remember the true heroes: the festival attendees, the neighbourhood residents, the grassroots community organizations, and the emergency medical personnel who served the victims and witnesses. Let us remember that we keep ourselves safe, and that the power to mourn, to heal, and to defend ourselves, lies in our people.

Information about Luksang Bayan vigils across the country is available at https://www.luksangbayan.ca/

Email info@luksangbayan.ca or contact @bayancanada on Instagram to submit information about upcoming memorial activities.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate