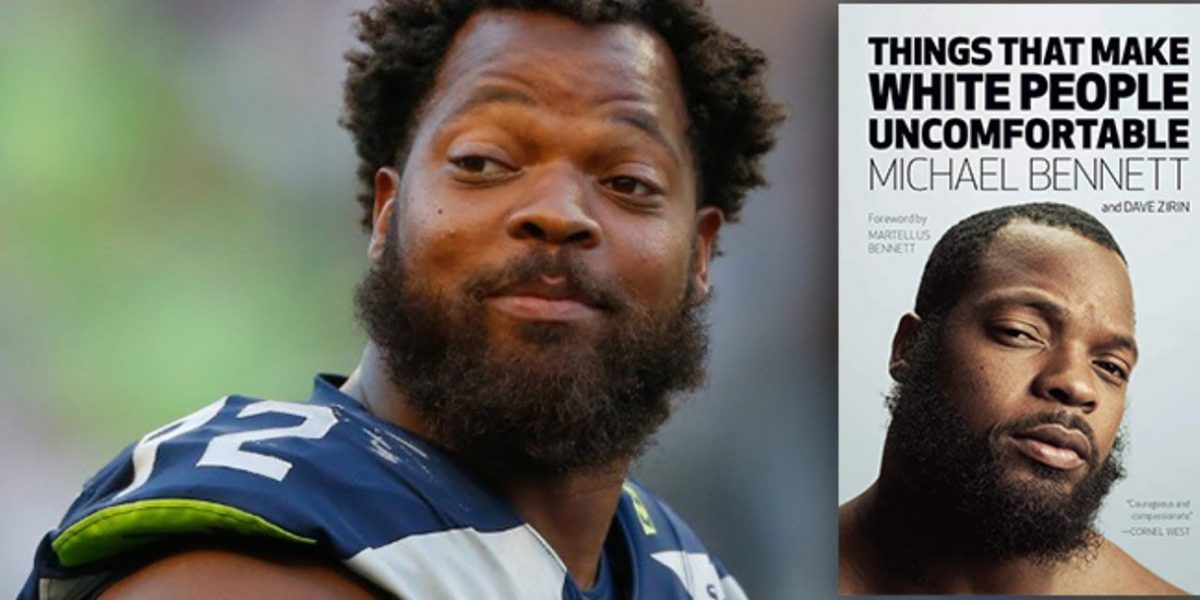

Things That Make White People Uncomfortable by Michael Bennett and Dave Zirin (Haymarket, 2018)

Although written two years ago, the themes in Michael Bennett’s Things That Make White People Uncomfortable could not be more timely, with the growing number of US professional football players (and other athletes) speaking out to support Black Lives Matter (BLM). Bennett is a Super Bowl champion and a three-time Pro Bowl defensive end who played in the National Football League (NFL) for 10 years and is currently a free agent. In his book he explains how both his personal experience growing up Black and his involvement in the NFL led him to be highly visible and vocal in his support for Black Lives Matter. The book is co-authored by the popular Marxist sportswriter Dave Zirin, sports editor for The Nation.

In the last month alone, we have seen improvements take place that would have been inconceivable even six months ago—with everything from NFL commissioner Goodell now encouraging teams to hire quarterback Colin Kaepernick, to stadium sponsor FedEx calling for the Washington team to change its name (as demanded by Indigenous groups for years), to the announcement that “Lift every voice and sing” (considered the “Black National Anthem”), will be sung before the US national anthem “Star-spangled Banner” ahead of every game. These changes did not come out of nowhere, or out of the goodness of the hearts of team owners. This book provides a fascinating and important account of one player’s perspective on the movement that forced these changes into being.

Racism in sports

Bennett begins by explaining why in 2016 he joined Kaepernick and others in refusing to stand for the national anthem: “I was thinking about American Nazis marching in Charlottesville… about Charleena Lyles who called Seattle police for help and they shot her to death… about my friend Colin Kaepernick… about the gap between what we are taught the flag represents and the lived experience of too many people. I was thinking about all of this, and as the anthem started to play, I sat down. There was no way I could stand for the national anthem, and there was no way I would, until I saw this country take steps toward common decency.” He outlines the history of Black athletes speaking out, resisting calls from the right to “stick to your game” – from the same people who are happy to have players speak out for the military or do commercials “selling their kids sneakers they can’t afford.”

Related to racism is the treatment of college athletes who fall under the control of the NCAA – the National Collegiate Athletic Association. The Association allows scholarships for athletes but does not pay them for their work, while making billions in profits, and the safety of players in the particularly dangerous game of football is the least of its concerns. So Bennett has a special contempt for this organization, stating “The main sports in this country built around Black Americans are football and basketball. The only revenue-producing sports in which you are not paid before you reach the top leagues are college football and basketball. This is not a wild coincidence. We tend to come from communities that are the least empowered, the most desperate for opportunity, so we get the shittiest end of the stick.”

No sooner do a tiny percentage of successful college football players make it to the NFL, than a whole other level of exploitation sets in. The absence of Black coaches, owners, and broadcasters means Black players have little voice. Right-wingers will say, “‘You got money, so why are you saying that you feel like you have no voice?’ But your money is tied to your silence.” And this is why Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling during the playing of the national anthem had such a ballistic response from the right.

Shake up the world

In a chapter titled “Brotherhood”, Bennett celebrates his five years with the Seattle Seahawks, particularly how the players supported Kaepernick and the fight against racism. And he comments on how players from other teams took notice, to which he says “more players could be themselves if they just tried. It’s like that expression, ‘You don’t know you’re chained until you try to move.’… If nothing else, sports offers us a platform, both culturally and financially, to try to effect the kind of change that can transform entire communities and even shake up the world.”

Just before his chapter on BLM, Bennett writes a “Time Out” in which he lists the names, ages and cities of 68 unarmed people murdered by police in the US in 2017 alone. The list includes people of all backgrounds, not just Black: “I believe that we never hear about many of these cases because if police violence is painted exclusively as ‘a Black problem,’ then it’s easier to keep us divided.” He views support for and participation in BLM as a crucial way of demonstrating hope. He emphasizes the importance of support from both Black and other people as the key to success: “But we’re not going to come together without trust, and I don’t see trust being built until white people say, ‘Black lives need to matter as much as white ones.’ When a white person gets involved, other people take notice.”

In other chapters Bennett demonstrates his all-round progressive, anti-establishment views when he takes on the food industry for its destruction of lives, and when he celebrates women’s liberation by publicly supporting the Women’s Strikes for Equality. He says he learned to support intersectionality from Muhammad Ali’s identification with the Viet Cong, from Olympic protesters Tommie Smith and John Carlos who were standing up for people in South Africa and Rhodesia living under apartheid, and from Black Panther Fred Hampton’s work with Native Americans, poor whites and gay people. “That’s why you see me working with Native Americans, Palestinians, women, and people in Africa and Haiti.” (and supporting Bernie Sanders’ campaign.)

Organize!

One of the last chapters of the book is probably my favourite, where he writes about the crucial importance of organizing for social and political change. Just looking at Kaepernick’s situation (of ostracization by the NFL) alone, he notes the fragmented nature of support. “Imagine if we’d had an organization in place by 2016. We could have lifted a lot of pressure off of Colin’s shoulders… It’s the lesson of the whole history of sports and politics.”

It turns out other top athletes, Black and non-Black, from across the sports world were thinking the same thing, which led to the creation of Athletes for Impact (A4I). One of its initial actions, after Bennett joined, was to publish a statement in support of Kaepernick. Its website, www.athletesforimpact.com is fantastic and one of its latest posts is a moving letter of support to Bubba Wallace, the NASCAR race driver who, after publicly supporting BLM, found a noose placed in his stall at the Talledega Superspeedway garage. Showing great vision, Bennett describes not only how this new organization has to stay “for and by athletes” (not coaches, owners, agents), but that over time it should extend its membership to include non-professional athletes, even teens. “Imagine a high school soccer player who wants to figure out how to use her position and leadership as an athlete to raise awareness in her school about violence against women.”A4I’s Manifesto is amazing. Its “Values” section speaks in support of inclusivity, the power of grassroots organizing, economic justice and internationalism.

In the concluding paragraph of the chapter, Bennett gives the last words to Nelson Mandela:

“Sport has the power to change the world… It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does. Sport can create hope where once there was only despair. It is more powerful than government in breaking down racial barriers.” But there is nothing automatic about this. It will take many more Michael Bennetts, and the politics of unity of BLM and other working-class movements, to create the conditions for a revolution that will get rid of capitalism and racism once and for all.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate