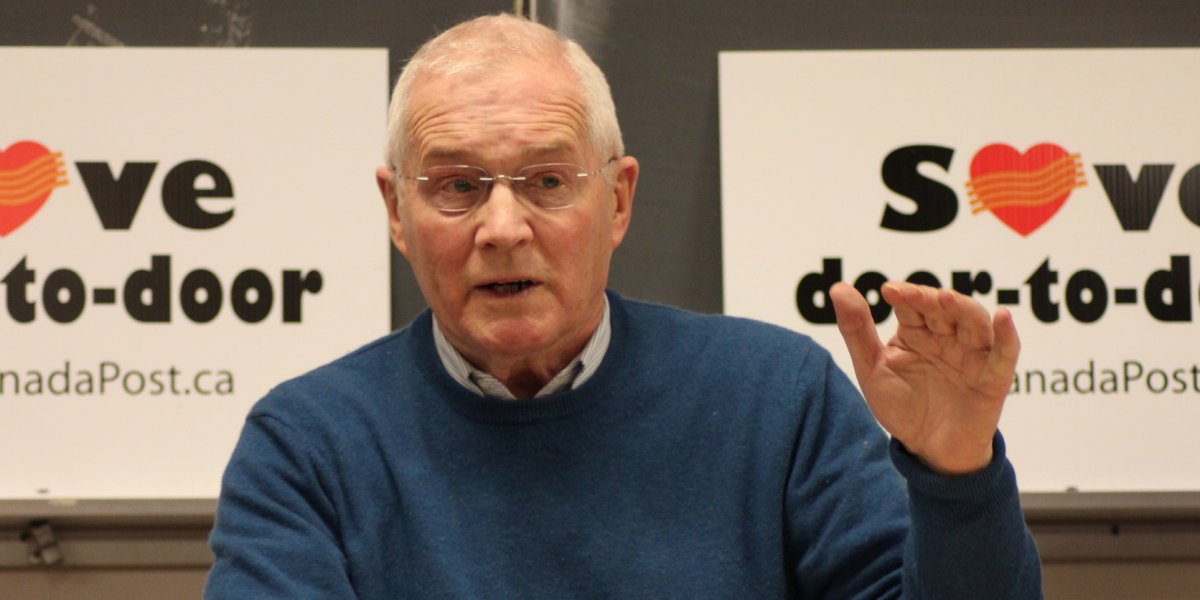

Ernest (“Ernie”) Tate, lifelong revolutionary socialist, died at home on February 5. He was 86. We send our deepest condolences to Jess MacKenzie, his companion of more than half a century.

With Ernie’s passing, the socialist movement has lost one of its fiercest fighters, someone whose deep commitment to working-class emancipation inspired nearly seven decades of political activity and changed the course of history. The greatest tribute we can pay to Ernie’s life is to share the countless lessons he leaves behind and pass to a new generation of revolutionaries the tools they’ll need to build a better world.

Ernie was born in 1934 in Belfast, Northern Ireland and grew up in the Shankill, a Protestant working-class neighbourhood. He left school at age 13 and completed a five-year apprenticeship as a miller before leaving for Canada. He arrived in the spring of 1955. A few weeks later, while wandering down Yonge Street on a warm Sunday evening, he discovered the Toronto Labour Bookstore, an event that would change his life forever. As he says in the first of his two-volume memoir, “this would be my first exposure to socialist ideas and the beginning of a life-long commitment to radical politics I have never regretted.”

For the next 66 years, Ernie grappled with the most urgent questions facing socialists of his day and, at key moments in history, intervened in struggles that had a global reach. His early life in Toronto follows the history of Trotskyism in Canada: first, as a member of the tiny Socialist Educational League, led by Ross Dowson, which by the early 1960s had grown into the League for Socialist Action (LSA); and later that decade and into the 1970s, as a prominent figure in the Fourth International. Even after he left the Revolutionary Workers League (the LSA’s successor organization) in the 1980s, Ernie remained active in the labour and social movements, and continued to engage socialists of any stripe who were serious about building organization and being active in working-class struggle. Among many socialist formations, Ernie participated in the Rebuilding the Left, the Greater Toronto Workers’ Assembly, and the Socialist Project.

The most important lesson his life demonstrates is the urgency to build revolutionary socialist organization: a grouping of like-minded activists who understand that the capitalist system cannot be reformed, but must be overthrown by the mass activity of the working class on an international scale.

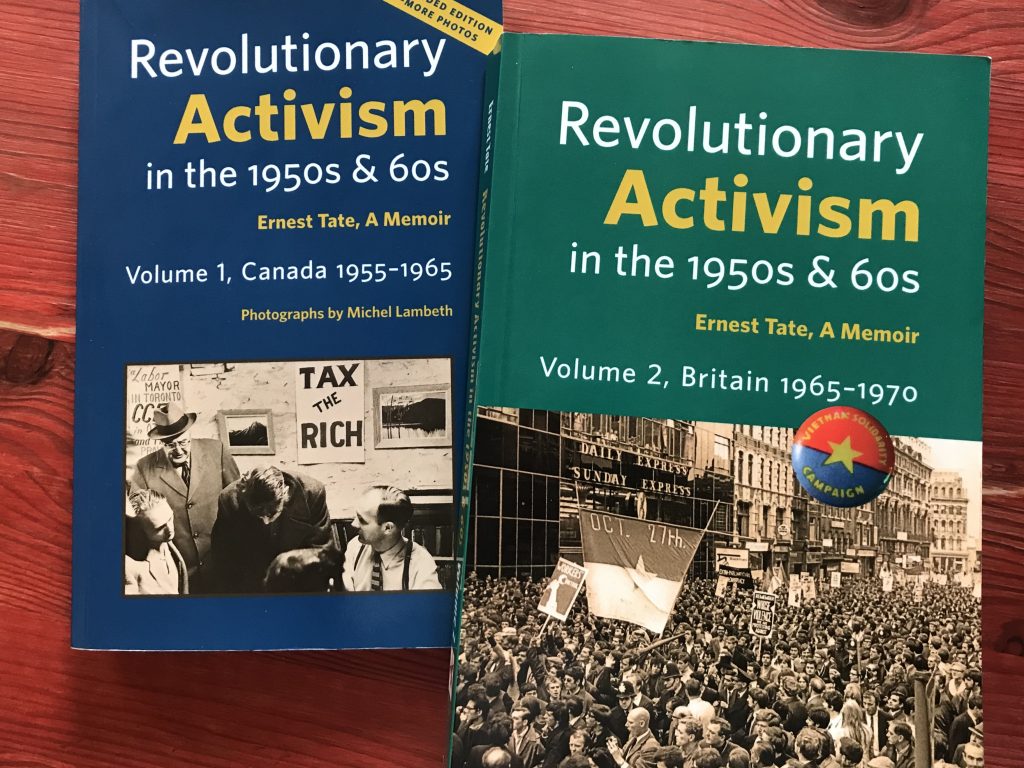

In his memoir, Revolutionary Activism in the 1950s & 60s, published by Resistance Books in 2014, Ernie documents the painstaking labour of this project: organizing regular political meetings, producing and distributing a publication of socialist ideas, going “on tour” across Canada to sell subscriptions to supporters, recruiting new members and developing them into cadre, intervening in key debates and struggles, developing a coherent and consistent set of politics, and learning and generalizing from the activity of the class. Performing any of these tasks is an achievement in the best of times; that Ernie and his comrades did so under the repressive conditions of the Cold War and McCarthyism makes their efforts all the more remarkable.

For Ernie, however, it was never enough just to “build the party”; it had to be an organization rooted in and among working-class people and their struggles, non-sectarian in nature, and constantly relating to events in the outside world. Ernie’s socialism was never from the sidelines, and always on the front lines.

The hard work would pay off. In the wake of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Ernie’s organization had enough skill, experience, and roots to lead a pan-Canadian solidarity initiative, the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, which successfully defended the revolution against Canadian attempts to back the US-led isolation of the island. Similarly, during his time as a socialist organizer in the UK, Ernie played a central role in launching the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign and Bertrand Russell’s International War Crimes Tribunal and in organizing two of the most successful, and influential, anti-war demonstrations in British history at the time. These actions gave expression to the growing anger at the US war and decisively turned public opinion against it. A young Tariq Ali, then a leading student figure on the British left, worked closely with Ernie in the movement, and Ernie helped recruit him to revolutionary socialist politics.

Ernie’s partner, Jess, herself a lifelong revolutionary socialist, is prominent throughout this history and in the events that followed. The central role she played in his life is captured in his memoir and by her frequent appearance with him as fixtures on the left in Toronto.

Ernie carried these experiences with him into other struggles later in life. During the Mike Harris regime in Ontario in the 1990s, he was part of a successful united front that blocked the Tories’ wholesale privatization of Hydro One. In the early 2000s, he was active in the New Politics Initiative, which connected with the rising anti-globalization movement and attempted to push the New Democratic Party to the left, and in the burgeoning movement against the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, where his insights about his own anti-war experiences decades earlier were invaluable. By the 2010s, Ernie enthusiastically welcomed the Egyptian Revolution and the Arab Spring, and helped build the growing movement in Ontario for decent work and a $15 minimum wage.

And in the midst of all these struggles, Ernie always made time to attend meetings, conferences, and gatherings of socialists all over the world. Most recently, for example, on the occasion of the centenary of the founding of the Third International, Ernie was one of only a handful of speakers from outside Latin America invited to speak at an international conference on Leon Trotsky and Trotskyism that took place in Havana in May 2019.

Never someone to seek the limelight, Ernie only ever conveyed his experiences in the most honest and direct manner, and with a deep sense of humility: every word and deed were guided by the goal of empowering the class and building its capacity to act. It was never about what he had done, but what you could do yourself.

At the heart of Ernie’s politics was the unwavering faith in the ability of the working class to liberate itself. And his commitment to revolutionary socialism was about doing everything he could to create the conditions for that to happen.

On a personal level, Ernie was warm, affectionate, kind, and generous. Throughout the time we knew him, first as an activist, then as a comrade and friend, he always found a way to encourage and support our activism, and offer advice on the ever-urgent task of party-building. He and Jess were active supporters of the Fight for $15 & Fairness campaign in Ontario, and joined hundreds for the year-end celebration of the passage of Bill 148. After publishing his memoir, Ernie urged us to write more about our own experiences as revolutionary socialists, and to encourage younger comrades to do the same.

We will always be grateful for the times we met Ernie and Jess for dinner at their home, and forever treasure the political education they passed to us over hours of conversation (and sometimes a few bottles of wine), at the same time as deepening our bonds of comradeship and friendship.

Reading about countless similar dinners in Ernie’s memoir, including the one with Verne and Ann Olson when they recruited him to revolutionary socialism, we were reminded of these special times with Ernie and Jess, and of the responsibility of socialists of all ages to engage, support, and learn from younger comrades. It is in these moments that we renew our commitment to this life-long project of human liberation, and strengthen the link between struggles of the past and struggles of the future.

While we mourn the passing of a true class fighter, we draw inspiration from his lifetime of revolutionary activity and find strength in the experiences he has left us. As revolutionaries, we can never really predict when the struggle of the class will rise again. We just know we have to be ready. And if you’re ready when it does, as Ernie’s life shows, you can change the world.

Thank you, comrade, and fare thee well.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate