More than a million workers have gone on strike across France against the austerity policies of Emanuel Macron. Spring Magazine spoke with Justin Appler, an Ottawa-based activist living in Paris and witnessing the largest mobilizations of the French workers since the 1990s. He attended the first day of the strike on December 5th, marching in Paris with a group of school teachers. On December 10th, he attended a demonstration to interview protesters to gain further insight into the broader implications of the national strike.

From Chile to Lebanon, we’ve seen huge mobilizations that have been triggered by specific austerity policies but that connect with longer standing frustration against neoliberalism. Can you explain the specific trigger of the general strike in France and the broader context?

The specific trigger of the general strike is attributed to the callous and elitist behaviour of French President Emanual Macron towards the working people of France. This is exemplified through the sweeping austerity measures his government has pushed through parliament since being elected in 2017. Macron was brought to power by an apathetic electorate who had grown weary of the established political parties. His government has a low favorability rating – sitting around 30 percent – largely because of the neoliberal reforms he has made since taking office, and his general approach to the plight of the working class.

Macron’s victory came in the wake of the collapse of the Parti Socialiste under François Hollande. In 2016, Hollande’s approval rating was 4 percent. Ultimately, he chose not to seek reelection, making him the first president of the 5th republic not to run for a second term. This precipitated a splintering of the French Left before the 2017 election. Benoît Hamon was leader of the Parti Socialiste and was forced to contend with two newly formed parties: the far left party La France Insoumise led by Jean Luc Mélenchon and Macron’s En Marche centrist party.

In the first round of the presidential election, Macron received 23.7 percent of the vote and ultimately received 66.1 percent of the vote in the second election round. The far right candidate for the National Front, Marine Le Pen, received 33.9. The last time the National Front made it to the second round (under the leadership of Le Pen’s father Jean-Marie Le Pen) was in 2002 against Jacques Chirac. He only received 17.8 percent of the vote.

In 2017, during the second election round, the people of France were confronted with a choice between two stark choices: the neoliberal pro-business vision of Macron and the far-right xenophobic vision of Le Pen, neither of which were appealing choices for the French Left. Macron’s En Marche party was viewed as the lesser of two evils. However, 9 percent of voters spoiled their ballot – the highest ever seen in the 5th Republic. The voter abstention rate was the highest seen since 1969. Just as in 2017, many disaffected left wing voters made up the bulk of those who did not cast a ballot or spoiled theirs. This serves as a clear sign that the French people are disillusioned with the political process.

The strike on December 5th was called by the unions in response to Macron’s plan to restructure the pension plans in France. However, those who showed up were also protesting cuts made to healthcare and education, and, in general, the overall tone and governing style of Macron. The general sentiment is that, under Macron’s proposed plan to eliminate the 42 pension schemes and introduce a universal pension (which would be governed under a new points-based system) workers would be forced to work longer and would receive a reduced pension.

France currently has one of the best pension plans in the OECD. French pensions represent 75 percent of a worker’s pre-retirement earnings compared to the OECD average of 58 percent. At the heart of the protest are transport workers, who would lose their special status under the proposed pension regime. At present, workers such as transport drivers (who perform jobs that are hard on the body and which require long shifts) are able to retire earlier. Such a benefit would be removed under the new plan. The idea of restructuring France’s complex pension system has been attempted many times before; however, due to massive pushback from unions, successive governments have failed. Ultimately, people do not trust Macron’s pro-business government to reform the nation’s pension plan in a way that would be fair for all workers. Many protesters donned signs that stressed that they were against the neoliberal regime of Macron.

Although 76 percent of French people support pension reforms, the public does not have confidence in Macron to be in charge of bringing them about. The strike is largely against Macron and his government, which does not have the support of the majority of the population. It is not solely about the issue of pension reform. In 2018, railroad workers were not able to stop Macron’s changes to their special status. Now, workers have come together from various groups (public and private sector unions representing a wide variety of workers, alongside non unionized workers, students, and the Gilet Jaunes (yellow vests).

Can you describe the protests–the numbers, diversity, slogans, and what people on the streets are saying?

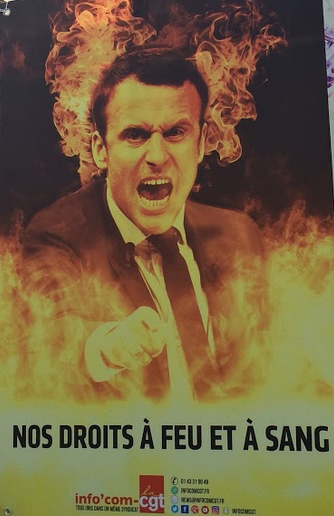

I had the opportunity to march with a group of teachers on December 5 and get their insights as to why these protests are necessary. Getting to our spot alongside other education workers was quite difficult because the streets were packed with strikers from the various unions. Each union had their own float which were blasting music and usually had a representative giving a speech of leading a chant. While we were waiting for the strike to start, there were many signs denouncing Macron’s governing style. The most notable was a sign which displayed Macron as a French king. Many protesters I spoke to stressed the point that Macron sees himself as a king and that he is only accountable to the wealthy nor does he have any regard for the struggle of working people.

Throughout the march I heard the following chants.

“Tout le monde déteste la police” (everybody hates the police)- many protesters explained that the police presence at the protests have become larger and more aggressive. During an interview I conducted after the protest with a teacher named Nour who I was marching with, I was shown a video of firemen pushing back police officers from the protesters, which she says is something they have not seen before.

“Plus chaud, plus chaud que la lacrymo” (hotter, hotter than tear gas) refers to the tear gas which is sprayed on strikers at these marches, and was used on the December 5th strike. Nour told me that the use of the tear gas has become more common and is no longer used as a last resort.

“Anti-anti-anti- Capitalisme” was often being chanted by groups of students.

“Jean Michel Blanquer, Ministère Autoritaire, On veut pas bosser pour toi” (Jean Michel Blanquer, authoritarian minister, we don’t want to work for you) – I was marching with teachers who were protesting the funding cuts to education and the hardships experienced by teachers (who have seen a rise in suicides this school year). Nour told me that the Minister of Education Jean Michel Blanquer claims that this has been one of his best back to school seasons, which completely disregards the suicides among the teachers he is supposed to be representing.

A few days after the strike, Nour also informed me that, at age 30, this is the biggest strike she has ever seen. She was shocked at how long it took the march to get started because of how many people were in the streets. We waited over an hour to start moving and, once we did, we were barely moving more than ten meters every twenty minutes.

In the streets, protesters were setting fire to trash cans and letting off color bombs which in the past have been used to obstruct police vision of the protesters. A few shop windows were smashed and there was a variety of graffiti on top of the wooden panels used to cover up store windows which were closed the day of the strike. Much of the graffiti donned anti-capitalist messages about who these shops serve and the inequality between the rich and poor in France. By the time we reached Place de la Bastille, confrontations between the police and the protesters had become fierce so I decided along with my fellow marchers to step into a cafe until things settled down. When we rejoined the march, we were able to make it to Place de la République where the police presence was strong. Throughout the day, our mobility was limited by a police presence that ensured the protesters could not make it too far off the main drag. We were unable to make it to Place de la Nation because of the sheer amount of tear gas being sprayed. This was around 6pm in the evening and the protesters began to disperse after nearly four hours of marching through the city.

When speaking with protesters on December 10th, the general sentiment is that Macron is a president for the rich. A young unemployed woman I spoke with told me that in the past there had been more of an effort for the ruling government to distance itself from the banks and the big corporations in terms of posturing. However, Macron has made it clear that he is a pro-business politician and will work for the interests of big business at the expense of working people. A lawyer who works for Confédération Nationale du Travail explained to me that Macron is continuing the work of Hollande but has ramped up the pressure to break down the French social system and further the neoliberalization of the French state. At both the protests on the 5th and the 10th there were a variety of communist groups present handing out literature. These groups were not connected with any of the unions, and were present in order to foster a greater consciousness concerning the need for greater change to the capitalist system. I spoke with two members of the Lutte Ouvrière who stressed the importance of harnessing the energy of these strikes to demand greater social change beyond just stopping the reform to the pensions. I spoke to a man who was holding a sign which pictured Macron wearing a crown and “Carrière Hachée Retraite À Chier.” (Jobs cut, retirement nonexistent). His wife said, “They want to take out pensions and put them in their pockets.” The general sentiment is one of distrust of the Macron government. The reforms he is going to make will only increase inequality and the pension reforms are being used to transfer wealth from the workers to the one percent.

Last year the yellow vest movement burst on the scene, connecting concerns about the environment with anti-austerity protests. How are the current protests related with the yellow vest movement?

While talking to protesters on December 10th, most of those I interviewed were firm in their belief that the yellow vest movement primed the French population to show their discontent with the Macron government on the streets. However, with or without the presence of the yellow vests, the plan to reform the pension plans would have caused a large stir. Further, the Gilet Jeunes have showed the people of France that protesting does work. It provided a renewed sense of the importance of solidarity between citizens, beyond just the protection that is provided by unions. This has encouraged the unemployed (and other workers who do not benefit directly from the unions who have called the strike) to come out and demonstrate their disdain for the neoliberal policies of Macron’s government.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate