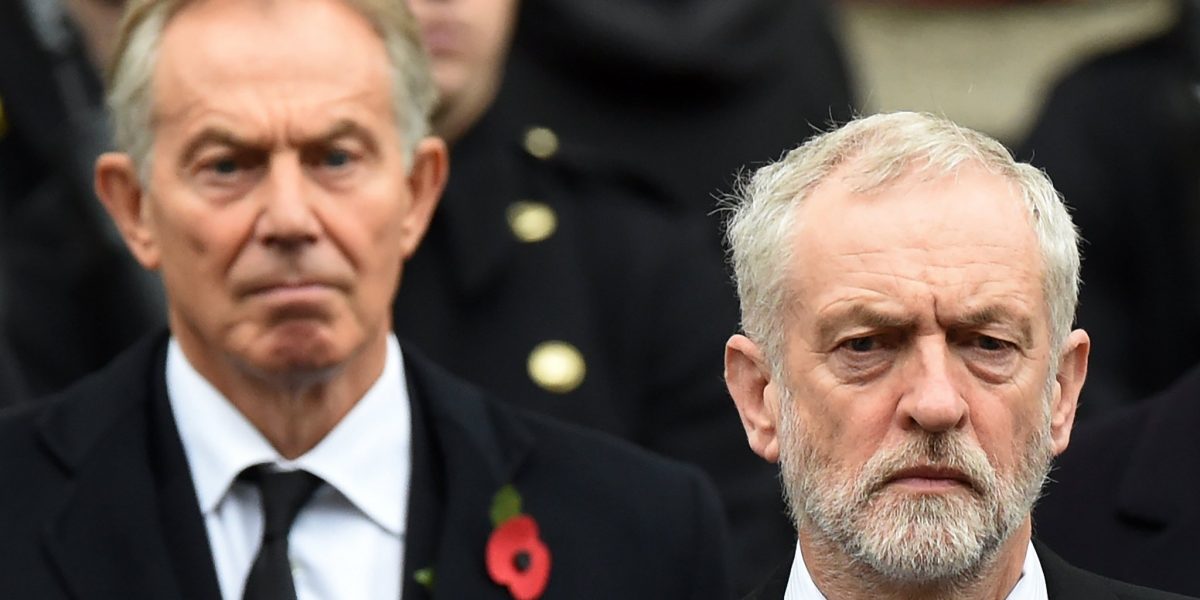

When Jeremy Corbyn won the leadership of the British Labour Party in 2015, it sent shockwaves across the social democratic world, becoming one of the most radical leaders ever chosen to lead a major social democratic party. For the past four years, he has faced a constant onslaught of attacks, from the media, from the right, and from the Blairite and centrist forces within his own party.

Corbyn survived a formal challenge to his leadership in 2016, winning a second leadership vote, and then surprised everyone by pulling one of the strongest Labour votes in decades in the 2017 general election, which destroyed the Tory majority and appeared to put Corbyn on the cusp of becoming Prime Minister.

The election result, however, represents a significant setback for those who had been inspired by Corbynism, many of us shocked and dismayed to see Boris Johnson win a massive majority according to the exit polls. What will certainly occur now is another onslaught against Corbyn but also against any aspirations for a radical leadership of the party. In the United States and Canada, centrists will point to the UK result as a sign that radical politics cannot win and choosing the likes of Bernie Sanders as the Democratic Party’s nominee, or running on a left platform in the NDP, all but ensures a similar defeat.

This poses serious questions for socialists, both those committed to Labour but also those who want to build a left beyond the Labour Party. What can we make of the Corbyn experiment? Why has it fallen short? What are the next steps that radical forces need to take to learn the lessons of the experience and build upon the radical shifting of political discourse that the Corbyn leadership has helped further. These are questions that need some explanation as working people continue to build fighting movements in the streets and workplaces against austerity agendas everywhere.

What went wrong

Immediately after securing the leadership, the Blairite and centrist wings of the Labour Party deemed Corbyn unelectable, despite him winning a massive share of the nomination vote, and went on the attack. After the Brexit referendum resulted in a surprise “leave” vote, those same forces upped their attack, arguing that Corbyn had not campaigned hard enough for “remain” and that he was partly responsible for the result. This prompted a second leadership race against the buffoonish Owen Smith that Corbyn won even more handily than his initial victory.

Despite the loss, reactionary forces were bidding their time, certain that Corbyn would lead Labour to an election disaster. However, when Theresa May called a snap election in May 2017, Corbyn came back from 20 points down to almost overtake the Conservatives. The campaign was filled with massive rallies, inspired by Corbyn and a policy manifesto that broke from the endless austerity offered by previous Labour and Conservative governments. By the end of the campaign, everyone was singing “Heeeey…Jeremy Corbyn.”

Antisemitism charges

The success of Labour’s 2017 election campaign forced the right wing in his party and in the press to deploy new tactics. Although the charge of antisemitism had been whispered previously against Corbyn, due to his unapologetic support for Palestinian causes, it became a focal point of criticisms of Corbyn’s leadership. Dozens of charges were raised against party members having made antisemitic comments and Corbyn was accused of creating an environment hospitable to antisemitism.

Although most of the charges were baseless or made in bad faith, the few legitimate ones were dealt with through party disciplinary bodies. Under constant pressure, the party executive also decided to pass the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliances’ definition of antisemitism in toto, despite it containing several problematic inclusions.

There are debates as to whether the accusations were handled properly by Labour, but it has become clear that the charge of antisemitism was going to be used as a bludgeon, irrespective of how many members and parliamentarians were expelled from the party or how often Corbyn apologized. Every compromise that Corbyn and others made only gave confidence to those making the accusations. This culminated in the ridiculous charge in the midst of the 2019 election by the Simon Wiesenthal Centre calling Corbyn the top anti-Semite of 2019. These kinds of accusations are not only hyperbolic, however, but also intentionally give a free pass to right wing violence against Jews (which has increased) while targeting Corbyn, largely for his sympathy with the Palestinian cause.

Brexit

The even bigger boondoggle facing Corbyn is the never-ending Brexit fiasco. The left in the UK has long held strong Eurosceptic sentiments about the EU, noting that many of its rules would hamstring many radical legislative reforms. Despite this, when David Cameron’s Conservatives called the referendum, Corbyn supported a “remain” position, while calling for changes to the EU. The ambivalence, shared by huge swaths of Labour votes, wasn’t good enough for the Eurofanatics in the Blairite wing, who wanted Corbyn to offer an uncritical support for the EU. It should be noted that Labour’s major advances in the 2017 election occurred when they were holding a People’s Brexit position, not offering up a second referendum.

Despite their failures to oust Corbyn and his successful election campaign, where he pivoted away from the Brexit question and focused on ending austerity, pro-Remain forces in Labour hounded his leadership for not calling for a second referendum. Despite the obvious electoral vulnerability this would produce among pro-Leave Labour voters and the chaos a second referendum would create, shadow Chancellor John McDonnell and Momentum Chair Jon Lansmen eventually pressured Corbyn to concede this point.

This has caused particular problems in this election, with many leave voters reticent to vote Labour this time as they did in 2017. Traditional Labour strongholds in the heartland of the UK, which voted for Leave were more susceptible to being flipped. 70 percent of marginals that Labour needed to win to form government were Leave ridings. Labour’s position on Brexit of having a second referendum made it much harder to win these seats, and allowed Boris Johnson to campaign on the very simple but focused slogan of “Get Brexit Done.”

While Labour announced a series of popular and bold left policy promises, it’s waffling on the key question of Brexit hamstrung its ability to gain a hearing in key marginals.

But the Tories have shown that they can’t in fact get Brexit done and if Corbyn had campaigned on getting a People’s Brexit deal through he could have avoided the electoral losses the party facedin the northern parts of England, devastated by neoliberal deindustrialization.

Election

Despite heading into the election down 15 points, Labour made significant headway. Over three million new voters have registered, mostly young voters under 35 that lean heavily Labour. Their manifesto has some radical solutions, including massive investment in the National Health Service (NHS) and nationalizing the telecom industry.

The Tory campaign was also mired by repeated problems, with Johnson performing badly, refusing to do interviews, and throwing temper tantrums when reporters called out the NHS funding crises. Revelations that Brexit could spell the privatization of health care only furthered people’s fears that a Johnson majority could lead to further austerity.

Despite this, Labour did not catch up in the same way they did in 2017. They remained between 5 and 10 points back in most polls. They had fewer mass rallies and the kind of electricity surrounding Corbyn in 2017 was not repeated. Despite having a lot enthusiasm around his campaign the constant attacks have had an impact. It did not help having a mainstream media (corporate and BBC) serving as an auxiliary force for the Tories, providing extremely biased and negative coverage of Labour, while soft peddling their coverage of Johnson, refusing to delve into his own past antisemitism and racist comments, nor the threat that a Johnson government would pose to the NHS.

Unfortunately, the results speak to Labour being unable to overcome all these obstacles, unable to overcome the Tories simple message and unable to shift the debate away from Brexit. While centrist forces in Labour argued repeatedly that Labour had to become pro-Remain to win, waffling on this question handed the election to the Tories, who appealed to an electorate exhausted of the Brexit issue. The landslide victory for the Tories was the direct result of the strategy pushed by the Labour right.

Which way forward

The knives will now be out for Corbyn and whether he is willing to hang in for much longer is questionable, considering his age and the amount of vicious attacks he has sustained. A leadership race will reveal a lot, with the likes of Emily Thornberry already positioning herself to run as a compromise candidate. Will the mass party that Corbyn has built be prepared to accept compromise with the right wing of the party that effectively sabotaged Labour’s electoral chances?

In terms of which way forward, those inspired by the Corbyn project need to ask tough questions both in Britain and beyond. How do we win in a party where a third of the membership goes out of its way to undermine any attempt to make radical change? How do we build beyond the electoral sphere, taking the radicalization that is occurring to the streets, to communities, to workplaces? There are no easy answers to these questions, but trying to figure out how we build upon the successes of Corbynism is essential for the Left everywhere.

For those across Canada and the US, we need to focus on continuing to build anything that advances radical ideas, but not only electoral campaigns. A left NDP effort or a Bernie Sanders campaign does a lot to broaden the audience of left activities, but efforts need to be made to take these ideas beyond vote-getting, into organizing efforts in workplaces, into picket lines, and into social movements fighting for significant reforms. In the United States, the Sanders impact has already seen a growing militancy among workers, more prepared to challenge their bosses, join unions, and build solidarity with others fighting similar fights. We need to do the same here in Canada.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate