Written in the centennial year of the Bolshevik Revolution over Tsarist Russia in October 1917, Vijay Prashad’s book traces the former Soviet Union’s influence on liberation movements throughout Asia and Latin America from its establishment in 1922 through to the first years of the Cuban Revolution in 1959.

Three themes entwine throughout Red Star Over The Third World. One is an overview of the myriad national struggles for independence and civil-rights in the years and decades surrounding the Russian Revolution. Another is the careful detailing of events which formed circuitous bonds between Soviet-communists, anti-colonialists, and nationalists. The third is a defense of the Communist International as a critical venue “to forge connections across continents.”

Prashad has written a history book in a literary style. Moments are framed in a manner which make it easy to imagine their setting. It is an emotionally effective method to convey the book’s central point: struggles are linked across time and space when there is organization. For example, readers are reminded that just as the French and Haitian Revolutions in the late 18th-century confirmed the belief held by 19th-century socialists that “ordinary people could rule”; the annual International Working Women’s Day marches of the early 20th-century provided the space for the first major “demonstration of worker power in Russia” which later informed the various strategies taken by Zapata in Mexico, Connolly in Ireland, Gandhi in India, and Mao in China. Although it is difficult to think of struggles emerging on a generational timescale, the lesson to take is that only organization allows for revolution.

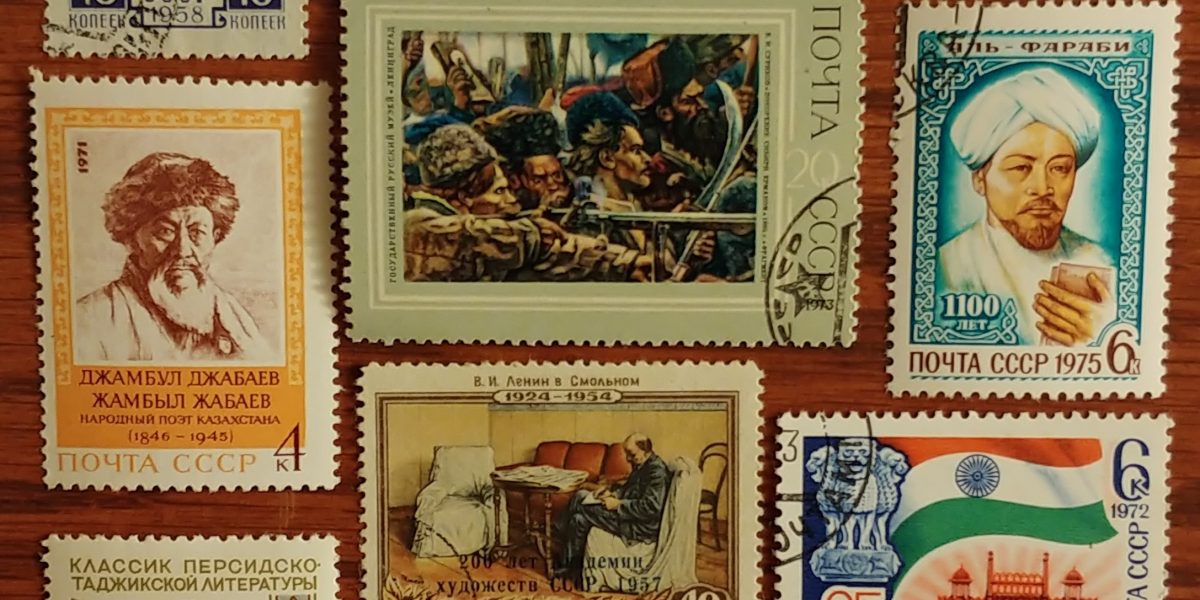

We learn that details of the Russian Revolution seeped passed censors across the colonized world, through poets, singers, journalists and writers. They became conduits who not only propagated the breakthrough in their respective homelands but also informed the Soviets of considerations they would later internalize. Prashad must be commended for (re)introducing figures such as McKay from Jamaica, Bharati from Tamil Nadu and Arce from Mexico and outlining how they, alongside many others, shaped the Soviets’ orientation on issues of ethnicity, women’s liberation, and religious freedom. Further, a critical overview of each of these considerations is tactfully offered.

Perhaps the books greatest quality lays in the many rich expositions which provide unfamiliar facts. To read of people from one country establishing communist parties in others, or of the women who made it a point to “create fronts to develop struggles led by women on women’s issues” is awe inspiring because such information is strikingly obvious after learning the fact. A similar feeling is had when Prashad describes the conjoined nature of colonialism and fascism and its arresting affect on many nascent socialist struggles from the Caribbean to Spain and beyond. Marshalling the amount of information required to knit this history together would have been a considerable undertaking, and providing it in a digestible format likely made the task even more difficult. In the book’s preface, Prashad credits several people for allowing these facts to live once again. It is important to recognize these contributors, one of whom is Toronto-based John Riddell; their commitment to shed new light on an underexplored past has allowed Prashad to deliver an original understanding of an admirable part of the Soviet project.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate