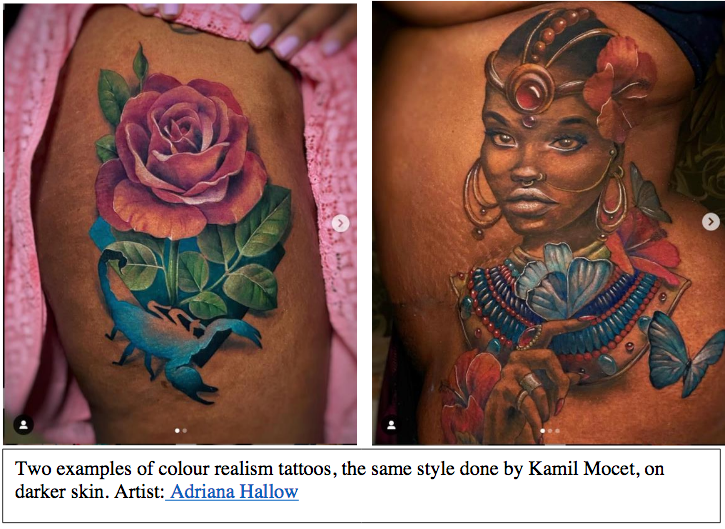

“Do you tattoo darkskin?” This question was recently posed to tattooist Kamil Mocet on January 13, 2021, a tattooist at High Voltage Tattoo in West Hollywood run by renowned artist Kat Von D. His response, “I wish. Unfortunately my style, technique and ink sets I am using they don’t look good on darker skin tone,” is emblematic of the rampant colourism within the tattooing industry. Mocet is one of many artists to refuse to learn how to accommodate different skin tones, blatantly discriminating against people of colour.

Local Hamilton artist Kat Gomboc was one of the first to point out how this response reflects deeper issues within the industry, particularly with the education system of tattooists. Gomboc reached out to Kat Von D., who responded, “the truth is, depending on how much melanin concentration the client has, will depend on what pigments show up properly. It would be unethical to promise people with darker tones that pigments will heal properly and look the same as if they were tattooed on lighter skin tone, while taking their money.”

When apprentices are faced with such statements by accomplished tattooists, they often lack the theory and authority to disagree. As a result, the industry reflects and perpetuates systemic racism and white supremacy through the imagery on tattoos, photographs of tattoos, and the apprenticeship of tattooists. But questioning the history of the tattoo industry and applying anti-racist practice can help tattooists expand their skill set, and help clients hold them accountable.

White supremacy

The refusal to design tattoos with suitable pigments and colour to suit a client’s skin tone is a choice –one that has deep ties to racism within the industry and systemic white supremacy.Historically, tattoos have been found worldwide as far back as 60,000 years ago in a milieu of cultures, including an Iron Age Pictish mummy. While Captain Cook may have introduced the Polynesian word “ta tau” (to write) in replacement of terms such as “pincing” the skin, there a common misconception concerning Cook’s introduction of tattooing to the British Isles. Within Europe, tattoos were found within both Greek and Roman culture in addition to the Picts, as well as the common pilgrim Jerusalem tattoo or stigmata tattoo, and alchemical tattoos.

John Bulwer, in his 1653 book Anthropometamorphosis, was one of the first to denounce body modification and liken it to primitivism, further underscored by the drawings of John White. Images of tattoo designs from Britain’s ancestors, the Picts, were represented on Indigenous peoples by White to show, “that the ancestors of the British were once as savage as the inhabitants of Virginia.” Furthermore, the switch from branding to tattooing prisoners commenced in 1717, with separate tattooing practices also occurring within sea farers. On top of the racist “Intellectual”movement against tattoos, this also cemented our pre-conceived notions of tattoos with Freak Shows and lower social class. While the popularization of tattooing in Western culture largely occurred through the designs of Sailor Jerry, which often used racist and culturally appropriative designs, sailor tattoos stemmed from a longer historical background of tattooing within Western culture–reflecting the deeply complicated history of tattooing, colonization, and Othering of racialized peoples.

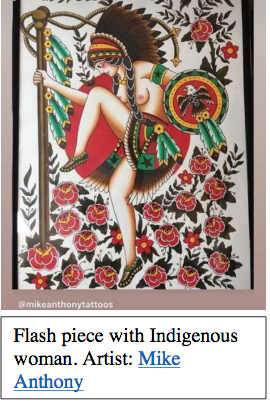

Reflecting the colonial origins of tattoos in Europe, racist flash sheets (pre-drawn design sheets), particularly of Indigenous individuals based in the notion of “the Noble Savage”and clown imagery based in minstrelsy, were common practice. Tattoos featuring cultural appropriation and racist imagery are still all too common, such as Brantford tattooist Mike Anthony’s recent flash artwork, which was heavily critiqued for fetishizing Indigenous women. Kandace Layne encourages other artists to research unfamiliar images and recognize that, “some [designs] are so sacred to other cultures that they may not want people tattooing certain designs or motifs without permission or initiation.”

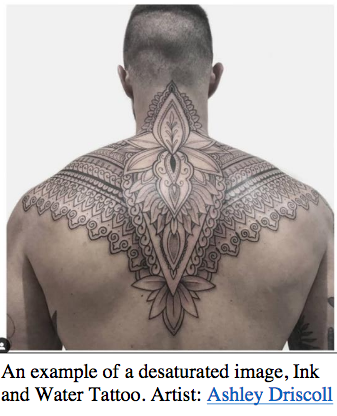

The distinct lack of representation of tattoos on darker skin is another issue, partially relating to the racist history of photography. Artists often post finished tattoos with skin tones that are naturally lighter, or even desaturate and edit their images which distorts their original work. While desaturating works on white skin may simply be used to hide redness and inflammation, the same implications are not true for darker skin. On top of systemic colourism privileging lighter toned individuals, desaturated photographs on darker skin may indicate the artist is unfamiliar or unprepared to accommodate their client, and are therefore hiding their mistakes.

Tattoo apprenticeships are a relationship between a single artist and their apprentice, meaning opportunities are often rare. Apprentices start with ‘shadowing’ the artist, practicing first on their own skin, then graduating to giving apprentice tattoos at reduced prices. Apprentices who learn in predominantly white shops often have few clients with darker skin tones, and do not build the skills and colour theory needed. Furthermore, BIPOC apprentices often face discriminatory attitudes within tattoo shops, putting the apprentice in a position of either giving up their opportunity to learn or facing such treatment. Toronto shops Ink and Water and Tapestry Collective were both identified for their hostile treatment of racialized and LGBTQ+ apprendices in early 2020, leading to the disbandment of Tapestry Collective.

Learning tattoo technique and anti-racist practice

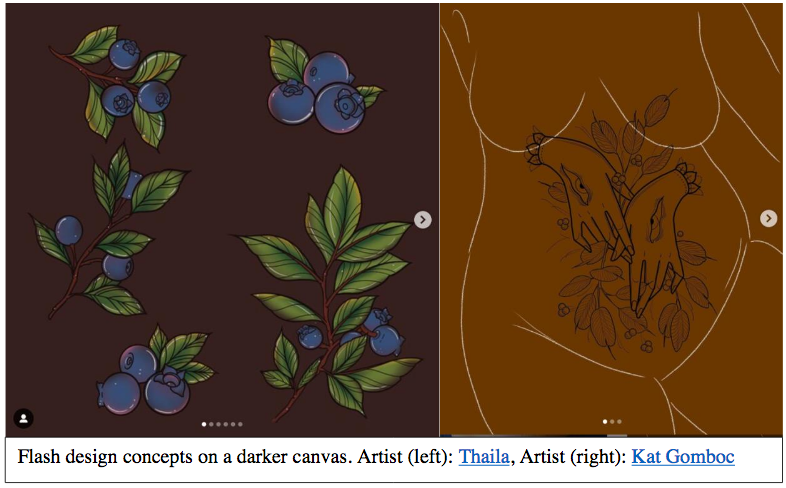

As tattooist Jade Chanel identifies in her post Tips on Tattooing Melanated Skin Tones, there are several distinct ways to accommodate. Firstly, designs may need to be tweaked for the client’s skin tone, particularly by choosing pigments that will suitthe client’s undertone. Tattoo artist Thaila (or Vegasink), suggests artists and apprentices apply their designs to a darker canvas, which can help to identify undertones and understand vibrancy shifts with different skin tones. Secondly, artists may need to use a contrasting stencil colour, rather than the commonly used purple/blue tone, instead using red or green. Chanel also suggests that tattooing and photographing in natural light is particularly important for darker skin tones, but artists can use a soft box to achieve a similar effect and reduce glare on the stencil, which is used as a guide for clean linework.

Black clients are significantly less likely to approach tattooists who lack consistent representation of tattoos on darker skin, especially considering many tattooists are not taught the necessary theory, thereby limiting their choice of artists and even tattoo style. Melanated skin has a higher number of fibroblasts, making the tattoo site initially puffy, which can also obscure details. However, if artists give time for the skin to settle (at least ten minutes) and use products such as Witch Hazel to reduce inflammation, they can produce a diverse and representational portfolio.

As for potential clients interested in getting a tattoo, look for diverse portfolios of artworkon social mediaand aim to support such tattooists.Welcome Home Studio has gathered a resource list of BIPOC artists in a direct attempt to address the ways in which white supremacy bars racialized tattooists from working within the industry. Furthermore, Thaila is in the process of opening Tru Tattoo Studio ,a shop run by BIPOC femmes in Toronto. Ink the Diaspora is an example of a Black-owned shop focused on bringing a platform of representation for tattoos on darker skin tones. They also provide opportunities for tattooists to learn anti-racist practices, such as their January panel It Cuts Deep: Understanding Colorism As A Weapon In Tattooing. As their founder Tann Parker writes, “You were taught that tattooing dark skinned people shouldn’t be a thing, that people are too dark to get tattooed. You were taught that and that’s clearly wrong.”

This is by no means a comprehensive coverage of the subtleties of colourism in the industry, but a call for artists and apprentices to examine their attitudes towards tattooing darker skin tones and an opportunity for them to begin to learn how to accommodate skin tones and actively learn anti-racist practices in their tattooing. Furthermore, this is an opportunity for clients to hold artists accountable to such practices and choose artists that uphold anti-racist behaviour.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate