It is with the exhaustion only an Indigenous woman can know that I write this, as I reflect on my work to release the records of residential schools, specifically records currently-held at the BC Archives, in the Royal BC (RBC) Museum.

The RBC Museum as an institution, and its staff (including those earning six-figures) continue to profit from genocide: through the callous display of stolen sacred items and ancestors, and the storage of genocidal records.

The RBC Museum displays the bones and belongings of countless ancestors from my nation, despite no legal ownership. What kind of institution protects and hides records of genocide, yet triumphantly displays precious and sacred objects without any semblance of protocol? This asymmetrical interpretation of ownership is racism, plain and simple.

Fighting for accountability

My fight for these records began in early July, although my Nations have long-sought accountability and redress from the Museum. In early July 10, I attended the museum, a site which also houses the decommissioned St. Ann’s schoolhouse. During this occupation, I read my demands for the museum aloud and shared them with attendees. Following that, through a series of text and email exchanges, I secured a meeting with senior leadership. That meeting and follow up has proven fruitless. While the RBC Museum proclaims its willingness to ensure survivors have access to records, I must correct this misinformation in the public record and identify the harms that the RBC Museum perpetuates.

The Catholic order known as the Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI), which operated nine residential schools, has stored records at the Museum since 1977, and added to this collection as recently as 2019. The Sisters of St. Ann, which ran four residential schools, also stores its records at the museum. This means that the BC Archives house documents from at least two Catholic Orders that operated Indian residential schools. The RBC Museum has knowingly been protecting records that document crimes against the Indigenous community for over 40 years. In light of continued confirmations of mass grave sites, the RBC Museum has attempted to mollify outcry from the Indigenous community.

We have called on all colonial institutions to release the records. Through meetings with museum leadership and communications with an archivist, it is clear that I cannot actually access the archival materials, despite misleading public claims that suggest they are available. The RBC Museum’s inaccessible process reflects the continued gatekeeping actions of colonial institutions. I have been repeatedly advised that the records do not belong to the RBC Museum, so they cannot be made available to me. In response to my demand for complete transparency, the RBC Museum has offered the possibility of a private viewing of the archives, for the sole purpose of identifying documents where a family member is named. They have said only my mother and I could attend this viewing. To impose these types of restrictions in such an emotional and triggering process is completely inappropriate, and reflects the colonial status quo at the museum. The RBC Museum has no jurisdiction in dictating how I, a Nuu-Chah-Nulth and Coast Salish Matriarch, shall access the records that relate to the genocide of my people.

Releasing the records requires museums, libraries, universities, government and any other colonial powers to uphold relationships with grassroots people. These records include the names of living murderers, rapists, and other violent abusers. Any person who knows a single detail about the location of mass burial sites must be subject to public scrutiny and justice. The perpetrators of genocide must no longer be protected. Direct pressure is the only tactic that works with this museum. Recent pressure and outcry from Indigenous people regarding the mass genocide of the residential school system has led to more truth. Yet, ignoring reconciliation, the Museum continues to take direction from religious orders, further protecting clergy, nuns, and other staff who committed atrocities at these schools. Rather than protecting any religious order involved in the operation of residential schools, the museum should proactively outreach and fund Indigenous communities to initiate the publication of these records.

A racist institution

The museum remains a systemically racist institution. This has been well-documented, including in the high-profile departures of former museum staff Sdaahl Ḵ’awaas and Nupqu ʔa·kǂam̓, two former Heads of the First Nations Department and Repatriation and Indigenous Collections. Nupqu ʔa·kǂam̓ named the museum a “wicked place,” stating that “the Royal BC Museum is established as a bastion of white supremacy, whose Indigenous collections are a gargantuan repository of trauma and violence. The vast majority of that collection was taken during the potlatch ban and residential school.” In June, an internal safety audit of the Museum concluded that acts of racism have taken place.

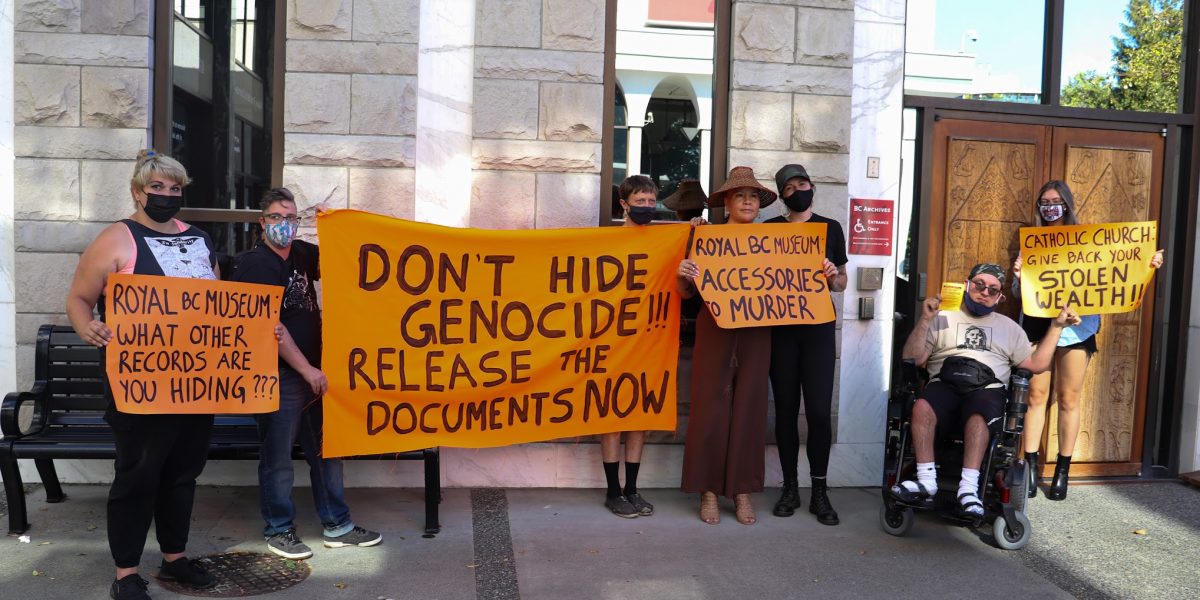

Settlersliving within the so-called province of British Columbia, and specifically those who reside on WSÁNEĆ (Saanich) and lək̓ʷəŋən (Lekwungen) territories, should amplify the statement “Every Child Matters.” Many of you have been moved by the unearthing of mass burial sites, and have joined memorials, worn orange t-shirts, and stood alongside Elders and survivors. Now it is time to hold the RBC Museum accountable. If you are a member of the museum, cancel your membership and tell the museum why. Talk to your friends and family members about this. Write to the museum. Call them. Show up on their steps. Write op-eds.

We must confront every single person who denies the genocide that occurs against Indigenous people. It is time to name the horrific actions of institutions that are complicit in the ongoing coverup of the annihilation against Indigenous people that took place in the residential school system.

We cannot decolonize racist institutions, we must remove them from our society.

To support the work of Xhopakelxhit and her Ocean Wolves, including access to archival documents held at the RBC Museum, visit her website, follow her on social media, and contribute to her Gofundme. Photo credit: Stitch.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate