In early July 2025, the Nova Scotia government abruptly terminated its contract with Out of the Cold (OOTC), a non-profit that had been operating two modular supportive housing sites in Halifax and Dartmouth. With just 30 minutes’ notice, OOTC staff were ordered off the premises by provincial officials and plainclothes security, ending a partnership that had provided shelter and support to some of the city’s most marginalized residents.

More than 60 people—many living with addiction, mental illness, and chronic homelessness—were suddenly left in limbo. At the same time, 42 unionized front-line workers lost their jobs with no prior warning.

This swift and secretive decision has sparked outrage from staff, residents, and community advocates alike, and highlights a deeper conflict over how governments respond to homelessness, substance use, and worker protections in the midst of overlapping public health and cost-of-living crises.

The decision to displace

After the Nova Scotia Department of Opportunities and Social Development (DOSD) ended its contract with OOTC, the province handed control of OOTC’s modular supportive housing sites over to the Atlantic Community Shelter Society (ACSS), a non-unionized organization.

Over the following week, a storm of public response followed—a rally was held, news coverage intensified, and competing narratives emerged from the government, the non-profit, and the workers’ union, SEIU Local 2, which represents the 42 laid-off staff.

The province claims the termination was due to “critical concerns” related to safety, security, and service quality, including improper sharps (i.e. needle) disposal, lack of staff training, and unsanitary living conditions. Officials say they lost confidence in OOTC’s leadership and felt urgent action was needed to protect residents. OOTC and its supporters, however, say they were blindsided by the decision, and warn that this sudden transition threatens both the stability of high-acuity residents and the livelihoods of dedicated front-line staff.

Stakeholders’ positions

The Nova Scotia government, represented by Suzanne Ley of the DOSD, denied that the decision was influenced by the presence of a union or by Out of the Cold’s harm reduction philosophy, insisting it was solely about resident well-being.

The Out of the Cold Board rejected this narrative, saying they had not been given the chance to respond to the most recent allegations. They expressed deep concern for the impact on both residents and staff, and emphasized the work they had done over the past year to strengthen governance, accountability, and operational systems.

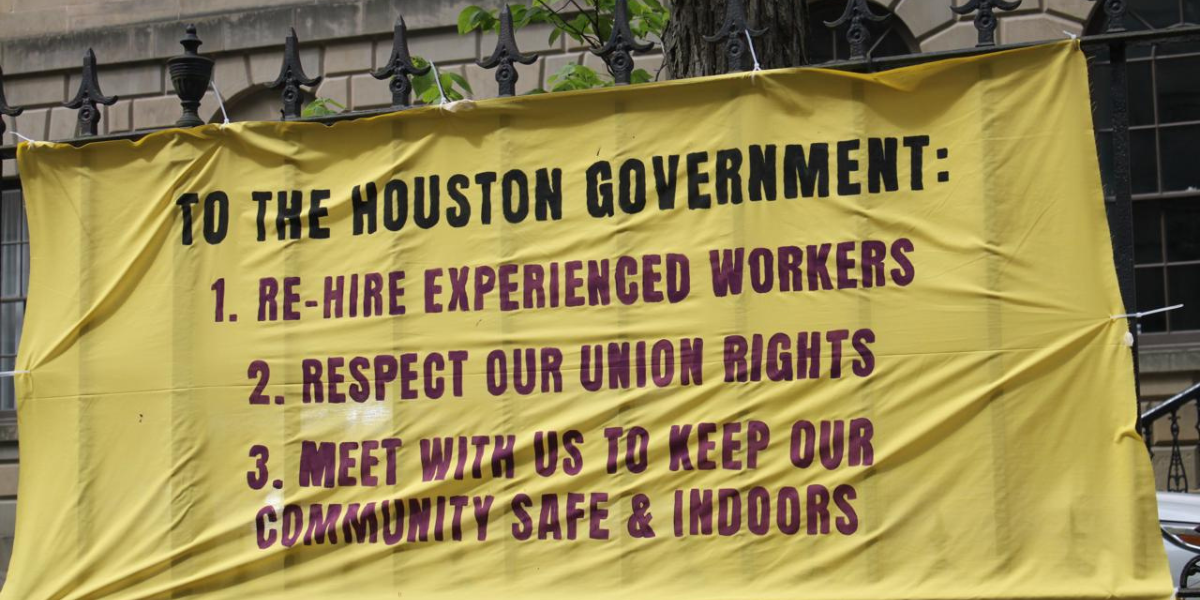

SEIU Local 2, which represents the 42 laid-off workers, called the move a clear case of union busting. Workers described themselves as compassionate, trauma-informed caregivers doing difficult work under pressure. They are demanding reinstatement, recognition of their collective agreement, and full transparency from the province.

Residents and housing advocates warn that the new provider may not uphold low-barrier principles. They say OOTC was one of the only spaces where people were accepted “as they are”—without sobriety or treatment requirements.

Harm reduction vs. the province’s approach

Out of the Cold operated on a harm reduction model that prioritized low-barrier, trauma-informed, relationship-based support. Residents were not required to be sober, medicated, or enrolled in treatment programs to access housing. Instead, staff focused on meeting people where they were at—offering dignity, stability, and care to those who are often excluded from more institutional forms of shelter. This model has been especially vital for residents living with complex mental health needs, active substance use, or long-term homelessness.

Following the contract termination, the province stated that harm reduction would “continue” under the new provider, Atlantic Community Shelter Society (ACSS). However, the lack of a clear public commitment to low-barrier practices has sparked concern. Front-line workers and advocates fear a quiet shift toward abstinence-based or compliance-driven models, which often prioritize “housing readiness” over immediate access to safe shelter.

This shift could have devastating consequences. Many residents do not meet the expectations of traditional shelters, and are only able to access housing through OOTC’s inclusive approach. A move away from harm reduction risks pushing high-acuity individuals—those with the most need—back into encampments, hospitals, or jails. It raises fundamental questions about whether housing is being treated as a human right, or as a reward for compliance.

Voices from the ground

The people most affected by the province’s decision—front-line workers and residents—have been outspoken in their grief, anger, and worry. On July 15, more than 200 people, including shelter workers, members of SEIU, and other community members, gathered for a rally outside Province House, chanting that, “Housing workers are here to stay / We won’t back down or go away.” A sea of protest signs read, “Houston Gov’t Is Union-Busting” and “Housing Workers Are Not Disposable.”

Julie Brown, a Resident Support Worker at OOTC since it first opened, summed up the sentiment shared by many:

“The actions of the provincial government to abruptly close Out of the Cold are appalling. The sudden and unexpected closure that took place last Tuesday was undignified for our team and residents we serve. There was no need for it.”

While some workers acknowledged internal challenges at Out of the Cold, they emphasized their deep commitment to residents. Many had spent years building trust and providing trauma-informed care in a difficult environment, often without adequate support. They did not defend management, but they defended their relationships, their work, and the residents who relied on them.

Some residents expressed concern about the future, particularly regarding changes to harm reduction policies and staffing. Long-time tenants feared displacement if the sites were to become abstinence-based, while others were wary of new staff unfamiliar with their needs and experiences.

Carlo Cininni, a Resident Support Worker at the Dartmouth site, criticized the government’s decision, asking:

“What message is the government sending about how it values workers and the most vulnerable in the province by abruptly laying off unionized housing workers during a housing and cost-of-living crisis?”

Austerity, union-busting, and the housing crisis

At its core, the removal of Out of the Cold’s operations is not merely a story of bureaucratic mismanagement—it is a case study in how austerity, union-busting, and neoliberal housing policy converge. Nova Scotia’s housing crisis continues to deepen, with skyrocketing rents, an overwhelmed shelter system, and a rising number of unhoused and disabled people. The modular units operated by OOTC were never designed as permanent housing, yet they became de facto homes because the broader system failed to offer any real alternatives.

The abrupt termination of OOTC’s contract—firing 42 unionized staff without notice and replacing them with a non-unionized provider—is part of a growing pattern of contract flipping. This tactic, which is illegal in Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia, allows governments to sidestep collective agreements and reassert control over service delivery through cheaper, more compliant operators. It treats front-line workers as disposable, despite their vital role in building trust and care in high-acuity settings.

Meanwhile, harm reduction is increasingly under attack. Across Canada, the language of “safety” is being weaponized to justify the rollback of low-barrier services. In practice, it often means removing workers who refuse to police the poor or force residents into overly medicalized models of recovery.

The real crisis here is not that the management of OOTC made mistakes, but that it was expected to fill the void left by decades of cuts to social housing, mental health care, and income support—then scapegoated for struggling under that impossible amount of pressure.

What comes next?

As the province moves forward with the Atlantic Community Shelter Society servicing the former OOTC locations, there are growing calls for transparency and public accountability. Who monitors the quality of care? Will residents’ needs still be met? And why were experienced, unionized workers cast aside without due process? SEIU Local 2 is demanding that these workers be rehired under their collective agreement, and many in the community support that call—not just for justice, but for continuity of care.

This moment also demands a deeper reflection: What does it mean to provide housing with dignity? And more urgently, who gets to decide how that care is delivered and by whom? The answers to those questions will shape not just the future of these two modular sites, but the direction of housing justice in Nova Scotia for years to come.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate