Set the Night on Fire: LA in the Sixties by Mike Davis and Jon Wiener (Verso, 2020)

Mike Davis died last month after a long struggle with cancer. For many socialists, Davis’ work documenting working class struggle and urban development, particularly in Los Angeles, inspired and amazed. Davis wrote accessible yet penetrating analysis, which condemned the absurdity of how capitalism created cities that isolated and marginalized the working class, and also provided hope when documenting the struggles against capital-driven urban development.

Davis is most famous for his ground-breaking account of the emergence of Los Angeles in City of Quartz and his look at the cultural imagination of the ecologically fragile city in The Ecology of Fear. Yet Davis’s final book, which he co-wrote with Jon Wiener, Set the Night on Fire: LA in the Sixties shows us that even toward the end of life he remained one of our pre-eminent radical historians. Davis and Wiener have managed to craft together stories of parallel and competing accounts into a coherent and gripping history of resistance and struggle.

Repression and resistance

Although constrained within the borders of the City of Los Angeles, Set the City on Fire still manages to provide a broad account of the social movements that reshaped the city and the state. While the popular conception of California is as a bastion of liberalism and counterculture, incredibly conservative and racist forces politically governed the state and its largest city. Repulsive figures like Mayor Sam Yorty and police chief William Parker ruled with unchallenged powers, largely through exploiting fears among white Angelinos and terrorizing Black and Chicano populations with state violence. Rabid anti-communist Ronald Reagan would become Governor of California in 1966 and used his office to attack radicals, most famously Communist Party and Black Panther icon Angela Davis.

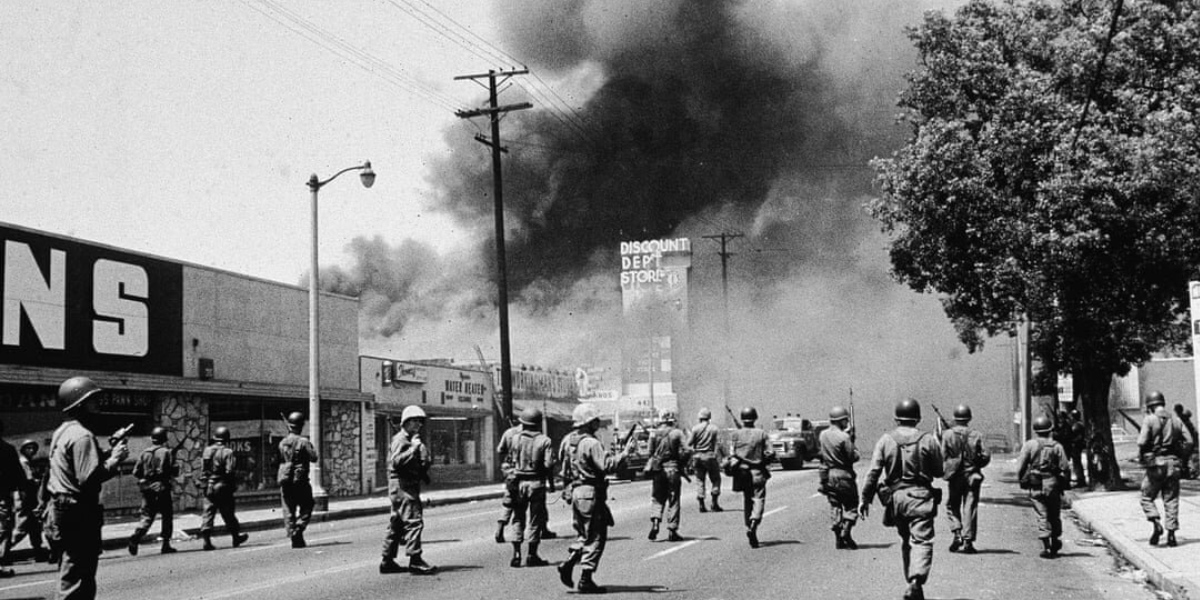

While the forces of reaction were powerful, Davis and Wiener focus on the social forces that mobilized despite the repression. Topics covered in depth included: the battles against segregation and for civil rights, the rise of the Black Muslims and Malcolm X, the struggles for fair housing, the “Ban the Bomb” movement, radical radio stations and newspapers, the birth of the Gay Liberation movement, nuns fighting against the Catholic Church’s reactionary leadership, the Watts Uprising, the rise of Black Power and the Black Panther Party in LA, the anti-War movement and the battles against the draft, rebellions inside Black high schools, the terror and repression of the state, the struggle against gentrification of public beaches, the Chicano population moving toward radical politics, women’s’ liberation, the health care radicalism of the Free Clinic. This gives you a sense of how broad, detailed and intersectional a book Davis and Wiener have produced.

Set the City on Fire, in giving such an exhaustive account, provides voice to those who led and participated in the multitude of social struggles and uprisings in 1960s Los Angeles. It doesn’t shy away from the often complex and fraught interaction that different resistance movements had with one another, whether dealing with misogyny in the Black liberation struggle or racism inside the anti-war movement, but it does give a sense of how these movements tried to work through these to build stronger and broader modes of resistance.

Legacy and hope

Although by 1972 most of the organizational forms of resistance that emerged in the 1960s had become defunct or destroyed, the latter often by brute state violence, Davis and Wiener do not end on a pessimistic note. They conclude that the radical movements of the decade helped shape the minds of the children and grandchildren of those who were on the streets in the 1960s. This intergenerational radical consciousness has shaped incredibly successful campaigns such as Justice for Janitors and Migrant Amnesty, as well as the large mobilizations against the police violence of the LAPD.

It is in this hopeful conclusion that Set the City on Fire is most powerful. Although electoral results can be demoralizing, broad and big social movements (whether in 1960s LA or in Ontario against Doug Ford) can put the ruling class on the defensive, cut against efforts to divide the working class, and win tangible gains for ordinary people.

Mike Davis left us many incredible works but it is fitting that his last great book leaves us on this note of hope and optimism, that the world can be changed and that it is up to us to do it.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate