“To know what a culture insisted was marginal or deviant was to know what was in fact central.”

From the overturning of Roe v Wade, to the backlash against trans rights, to ‘anti-woke’ rhetoric – the policing of gender, sexuality and reproduction continues. This has a long history, but this same record shows there has never been a timeless gender binary, a monolithic ‘normal’ sexuality, or ‘traditional’ family values. These ideologies emerge from their social context, which reveals a changing history of control from above, and a dynamic history of self-determination from below.

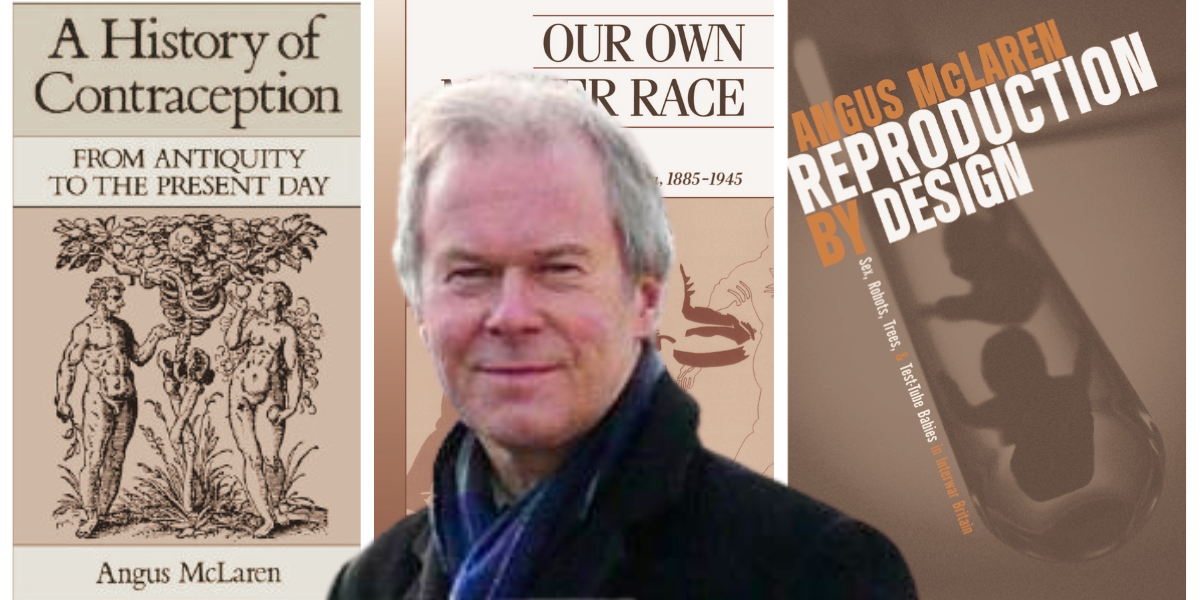

To better face the present we can gain insights from past repression and resistance, through the books of Angus McLaren, recognized as “an imaginative and prolific historian who has significantly increased our understanding of sexuality, gender and reproduction.”

A people’s historian

Born in Vancouver in 1942 to Scottish immigrants, Angus was raised in a religious family who opposed discussing sexuality—which piqued his interest in forbidden subjects. His mother was institutionalized for depression and given electroconvulsive therapy—a treatment disproportionately used on working class women in the post-war era—which led to his skepticism of medical authority. He was the first in his family to go to university, with a scholarship to study history at Harvard, but found the field focused on ‘great men’ which did not reflect his working class background.

But a research trip to Paris in 1968 coincided with the student rebellion. He read Michel Foucault’s theories on how legal and medical professions regulated and constrained sexuality. He was inspired by the Civil Rights and Women’s movements, and influenced by his partner Arlene Tigar, a feminist sociologist. He learned about the emerging field of social history that echoed these movements. As he recalled, “You can do this? This is history? You can talk about reproduction and women’s rights? I would love to do this sort of thing.”

His first book was Birth Control in Nineteenth Century England, published in 1978. As he summarized:

“Abortion has received little attention from historians because it has not been viewed as a ‘respectable’ subject of research. Quantifiers, moreover, are put off by the difficulty, if not impossibility, of establishing the incidence of acts which were illegal and therefore hidden from public scrutiny. One suspects, however, that a third reason for the lack of discussion of even the possible importance of abortion is the fact that the practice was a female form of birth control. Historians and demographers have until recently been reluctant to accept the notion that women would play an active part in determining family size.”

These themes guided his subsequent dozen books over the next 40 years, on the history of Europe and North America. First, a personal interest in people’s intimate lives that have been stigmatized by the clergy, criminalized by the state, and pathologized by the medical profession. Second, the intellectual challenge of documenting this hidden history by drawing from a wide range of sources: moral injunctions from religious to medical texts, testimonials from court transcripts to personal diaries, debates from conservative to socialist press, and popular culture from novels to films. And third, a political approach to history “both from above and below” that highlights the intertwining of class, gender and racial inequities, while stressing working class agency – especially women. What follows is a brief overview of his work, largely through his own words.

Sexuality and social order

Homophobia did not exist in ancient Greece and Rome: “The ancients’ concern was not with the sex act per se, which usually posed no ethical issue, but with whatever might possibly jeopardize the social hierarchy and family property.” As a result, in this patriarchal society, “there are no references to same-sex acts endangering Greek males, yet a long line of thinkers portrayed sex with women as dangerous.” Similarly, under the Roman Empire, “this was a resolutely inegalitarian society in which elite men always had at their disposal submissive and sexually available male and female slaves.”

The rise of the Christian Church saw a shift in ideology that redefined gender and sexuality: “Demonstrations of sexual prowess had been central to the Roman concept of masculinity. For Christians it was not unmanly to be celibate. With a shift in power from political to clerical office, new notions of sexual and marital renunciation cohered with the Christian ideals…The more extreme Christian thinkers ultimately objected to almost every manifestation of sexuality from abortion, contraception, divorce, and adultery to the wearing of wigs and the use of make-up.”

But a close reading of religious texts revealed the reproductive practices of women they were attempting in vain to control: “If stop signs imply the existence of traffic, the clergy’s ongoing condemnations of abortion and contraception can at the very least be taken as evidence of the continued employment of such practices.”

The development of capitalism led first to an increase in fertility in Europe and then a decline: “The growth of waged industrial labour initially provided inducements for early marriage and the bearing of children who would contribute to the family economy…Proletarianization and population growth thus went together.” But “with the fall in the demand for agricultural and unskilled labour, the large family lost its economic rationale…The fertility decline was indeed remarkable and took place in the absence of major improvements in contraception and in the face of the avowed public hostility of the medical profession, the churches, and the state. Clearly, enormous restraint and determination were exercised by millions of ordinary women and men.”

As European powers competed against each other, they were anxious about their fertility declines. While the middle class was allowed to restrict its family size, including through discreet access to abortion, there was growing hostility to workers doing the same. “In making abortion a statutory crime the ruling classes were asserting their rights to police the reproductive actions of the lower orders… The abortion laws were important, not because they necessarily made recourse to inducement of miscarriage any less likely, but because they signalled the intention of the medical and legal professions to intervene in matters of fertility control.” Physicians achieved a monopoly on health services by marginalizing midwives and opposing the contraceptive and abortion services they provided to women.

There was further criminalization and medical surveillance of working class women who, in response to economic circumstances, engaged in prostitution. This produced a series of serial killers including Jack the Ripper and Dr. Thomas Neill Cream, who took bourgeois morality to its logical conclusion: “When women seeking abortion were called killers, when prostitutes were portrayed as spreading disease, when women employing contraceptives to limit family size were charged with contributing to ‘race suicide’, it is not altogether surprising that a murderous backlash should have been precipitated… Although the police and the courts chose to present the women in the following murder case simply as victims, these women in fact played crucial roles in tracking down and convicting the killer”. But the dominant response was not to restrain ‘normal’ male violence towards women, but rather to police ‘abnormal’ male sexuality.

Trials of masculinity

Those who attack LGBTQ rights today often claim that gender and sexual diversity is a modern imposition on traditional norms. But this claim ignores how recently such norms were constructed, and how forcefully they have been maintained. “The process of construction of what many in the West now assume to be natural, timeless male and female genders took place between the eighteenth and the twentieth centuries… Social transformation (such as the changing nature of men’s work, the rise of the white collar service sector, the reduction of the birth rate, and women’s entry into higher education and the professions) appeared in the eyes of anxious observers to have undermined the explanatory powers of older notions of masculinity and femininity.”

Extreme effort went into creating an ideology “that sex and gender – the biological apparatus and the appropriate social behavior – were in effect inseparable. Men were masculine and women were feminine. Yet those who were most strenuous in their claims that these ‘natural’ couplings were powerful and predetermined often expressed in the same breath the contradictory fear that the linkages were so fragile that they had to be closely policed and enforced.”

Medicine and law, “two key systems of gender regulation,” pathologized and criminalized any deviance from the ‘normal’ aggressive, cis-heterosexual male – with new terminology including homosexual, transvestite, sadist, masochist, and exhibitionist. This not only led to state persecution – including Britain’s greatest playwright, Oscar Wilde – but it also fueled crime and violence, just as it had with laws against abortion.

“Blackmail trials demonstrated that just as the law had made homosexuals into criminals, so too had it made desperate women into outlaws.” Starting with homosexuality and then abortion, sexual blackmail surged to target any class, gender, or racial diversity: “The moralists’ strenuous attempts to organize, police, and control heterosexual desires provided blackmailers with an expanding pool of potential victims.” The criminalization of sexuality was also racialized. In the US the Mann Act, or “White-Slave Traffic Act”, purportedly designed to protect women from prostitution, was deployed to criminalize inter-racial relationships, and encouraged racial violence: “Southern racists – who with impunity assaulted black women – had long argued that the protection of white women justified the lynching of black men.”

Our own master race

WWI disrupted Victorian norms of gender and sexuality, as the state encouraged women to enter the workforce and provided condoms to curb sexually transmitted infections in the military. The end of the war also raised the spectre of sexual liberation, with campaigns from Emma Goldman to Alexandra Kollontai. “The legalization of abortion in Russia following the 1917 revolution proved the safety of the procedure but confirmed in the mind of its opponents its association with the forces subverting existing class and sex relations.” Germany in the 1920s had networks for contraception and abortion, and Magnus Hirschfeld campaigned to support gay and trans rights.

But middle class reformers like Marie Stopes and Margaret Sanger advocated the medicalization of birth control to stabilize the heterosexual family and control working class reproduction. “Birth control ideology was embraced by the middle classes once they understood how it could be turned to the control of the reproduction of the lower orders rather than their liberation…It was a cruel irony that many of the eugenically-minded doctors who opposed the family limitation of the ‘fit’ were clamouring for the forced sterilization of the ‘unfit’…Eugenic arguments provided apparently new, objective scientific justifications for old, deep-seated racial and class assumptions.”

In 1933 BC joined Alberta in legislating coercive sterilization, while Ontario continued without legislation into the 1970s. “In place of medical diagnoses the eugenics board relied on the social criteria of what represented ‘normal’ morality, sexuality, and work habits to classify their charges.” Those coercively sterilized were disproportionately poor, disabled, Indigenous, and female.

In the 1930s Stalin reversed reproductive justice in the USSR while the Nazis sent homosexuals to concentration camps, executed abortion providers, and forcibly sterilized the ‘unfit’. “The Nazis launched campaigns of massive state intervention with the intention of reconstructing motherhood, eugenics, and sexuality. Sterilizations led on to euthanasia and euthanasia to the final solution of genocide. Jews, communists and women were targeted… Since homosexuality was a crime in Anglo-Saxon countries, the history of the Nazi persecution of sexual minority groups was ignored.”

The bedroom and the state

After the dislocation of WWII governments again attempted to reimpose gender roles and police sexuality. But women and gay liberation movements won a series of partial victories.

Campaigns defeated the laws against homosexuality, while sexologist Alfred Kinsey normalized the wide spectrum of human sexuality. But the policing of sexuality shifted from criminalization to medicalization, with harmful psychiatric or endocrine treatments. Those who today oppose gender affirming care are those who last century supported coercive hormone treatments. “Whether it was in encouraging the reproduction of the fit or limiting that of the unfit, defending heterosexuality or ‘curing’ sexual deviancy, the eugenically minded sought to turn endocrinology to the purposes of policing reproduction.” But the Stonewall rebellion launched a movement for LGBTQ liberation.

In the 1960s contraception was also decriminalized, alongside the commercialization of the pill. In Canada a mass movement defeated the abortion law, and revealed its ongoing faultlines. “The abortion reform groups that rallied to Morgentaler’s defence opened a new chapter in the Canadian fertility debate. Some of the older supporters of family planning found the feminism and radicalism of the new pro-choice activists disconcerting. Many doctors, though in favour of decriminalization of abortion, were opposed to the slogan of ‘abortion on demand’ because it represented a shifting of power from the physician to the patient.”

Reproductive justice has yet to be won, and what Angus and Arlene wrote in their history of abortion and birth control in Canada decades ago remains today: “The consequences of birth control services becoming increasingly bureaucratized, professionalized, and commercialized have been both liberating and coercive. On the one hand, access to safe and effective birth control and abortion has improved a great deal…On the other hand, the birth control services, by ultimately being managed and controlled by the government, scientific community, medical profession, and pharmaceutical industry, have often not increased women’s sense of controlling their own fertility. They have often been provided services unequally, coercively, and abusively…As abortion has become a safer procedure, it faces the danger once again, due to political opposition, of being driven underground and becoming again a risky undertaking.”

20th century sexuality, and beyond

There have been huge societal shifts over time. “We now lived in a culture in which – thanks to the contraceptive pill, abortion, and reproductive technologies – it was taken as a given that sex and reproduction were split.” From the oral contraceptive pill in the 1960s to Viagra in the 1990s, there have been repeated claims of a ‘sexual revolution’.

But “if such a revolution occurred the obvious question is why… the issues of pornography, prostitution, abortion, sexually transmitted diseases and homosexuality are still so hotly debated? The answer is that the old forms of restraint were no doubt displaced but new methods of containment emerged…A new balance was struck between the forces of change and those of order. Enlightened authorities recognized that liberalization could provide better, reconfigured means of control. They could accept a reappraisal of the sexual aspects of social conduct because it appeared to mirror a free-market mentality that valorized privacy. Capitalism, once puritanical, was now sensual.”

But new methods of containment rely on old inequities that need to be continually challenged. “Given the tenacity of class, gender, race and ethnic divisions, those seeking to control and discipline the marginal will continue to produce accounts to exploit the ‘dangers’ purportedly posed by sexual practices and desires…Racial discrimination, class differentiation, state manipulation and commercial exploitation all played crucial roles in shaping sexuality in the past, and all the indications are that they will continue to play such roles in the future.”

Sadly, Angus McLaren passed away a year ago. While this is personally painful, he left an inspiring wealth of knowledge about our past that can help guide our future. His legacy will continue through a scholarship at the University of Victoria, and the movements he documented will continue to chart their own history.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate