September 11, 2023 marks an ominous anniversary, fifty-years since a CIA-backed coup overthrew Chile’s democratically elected socialist president Salvador Allende. In office for barely three years, the Unidad Popular government brought through significant reforms and set off an extended period of industrial militancy that threatened the Chilean ruling class enough to embrace a brutal junta, whose impact continues to define the political landscape in Chile and beyond.

Euphoria of election

Allende had run for president three times prior to 1970, the perennial candidate of the Socialist Party and its coalition partners. Although popular he had not come very close to winning. A broad coalition of parties, including the formidable Communist Party, supported his campaign for president in 1970 and with the help of splits on the right Allende won the presidency with just under 37 percent of the vote.

Allende embraced what he termed the “Chilean Way to Socialism” that amounted to a more radical expression of social democracy but still one largely committed to an electoral-centred approach. Nonetheless, his administration pursued ambitious legislative moves, especially compared to Western social democratic parties that had conservatized over the decades. Allende followed through on his promise to complete the nationalization of copper and coal mines. The government also accelerated the land reforms of previous administrations, breaking up the old large estates and redistributing them, and pushed legislation to increase wages of the working class.

The Right reacts

Immediately, forces of capital (and especially the powerful forces, both domestic and international, that had controlled Chile’s copper industry) feared the kinds of the reforms that Allende would implement. Capital strikes and hoarding of goods became tools for the right-wing, helping to drive up inflation and undermine many of the reforms the Allende government had implemented.

The United States also quickly began to interject in Chilean affairs, worried that the Allende government would become a model for others in Latin America to pursue significant reform and form alliances with the Soviet Union. They had invested heavily to prop up Allende’s electoral competition but when that failed, they encouraged the kidnapping of the army’s chief commander to facilitate a coup before Allende took power. When this backfired, the always villainous Henry Kissinger helped start covert operations in Chile that developed relationships with the military, encouraged anti-Allende propaganda through the country’s largest newspaper, El Mercurio, and funded industrial mischief by forces opposed to the government, including the infamous trucker strike in 1973.

The working class responds

In response to the overt sabotage, the Chilean working class responded forcefully, setting up rank-and-file organizations aimed at undermining capital strikes and hoarding campaigns. Workers took over factories that had been abandoned by its owners, union organizations reopened shops and began coordinating distribution of goods. Cordones Industriales, industry-wide worker-managed organizations began to coordinate all these efforts and soon they were present across the country.

While workers saw their strikes, occupations, and redistribution efforts as supportive to the Allende government, the administration was cautious and worried that such sweeping efforts would provoke a more forceful reaction from the right and the military. Workers were advancing the agenda of nationalization much quicker than Allende desired. The government did not want alternative centres of popular power to undermine its authority and instead of encouraging their growth, Allende pursued negotiation with political forces to his right and agreed to demobilize the cordones in exchange for their support.

Lead up to the coup

Despite destabilization efforts, Unidad Popular actually increased its support, obtaining 43 percent in the parliamentary elections in March 1973. Although still not a majority, the political winds were at its sails and the right wing and its supporters in the military determined that electoral opposition was not enough. Right-wing forces began painting on walls the slogan “Jakarta is coming,” threatening similar military actions that had overthrown a progressive president in Indonesia in 1965.

As fears of a military intervention increased, the Chilean working class responded with increased militancy, increasing the role of the cordones, especially in response to the trucker strike that aimed to economically strangle the country. On September 4, 1973, on the anniversary of Allende’s election, huge demonstrations took to the streets of the capital, Santiago, with many workers shouting slogans encouraging the government to arm the masses to defend the government.

However, Allende never believed in a strategy of arming the masses. He hoped he could convince the military to respect the constitutional government. Even after Carlos Prats, the Commander-in-chief of the Chilean Army, no longer could control the army and chose to resign, Allende hoped his successor Augusto Pinochet would.

The coup and its aftermath

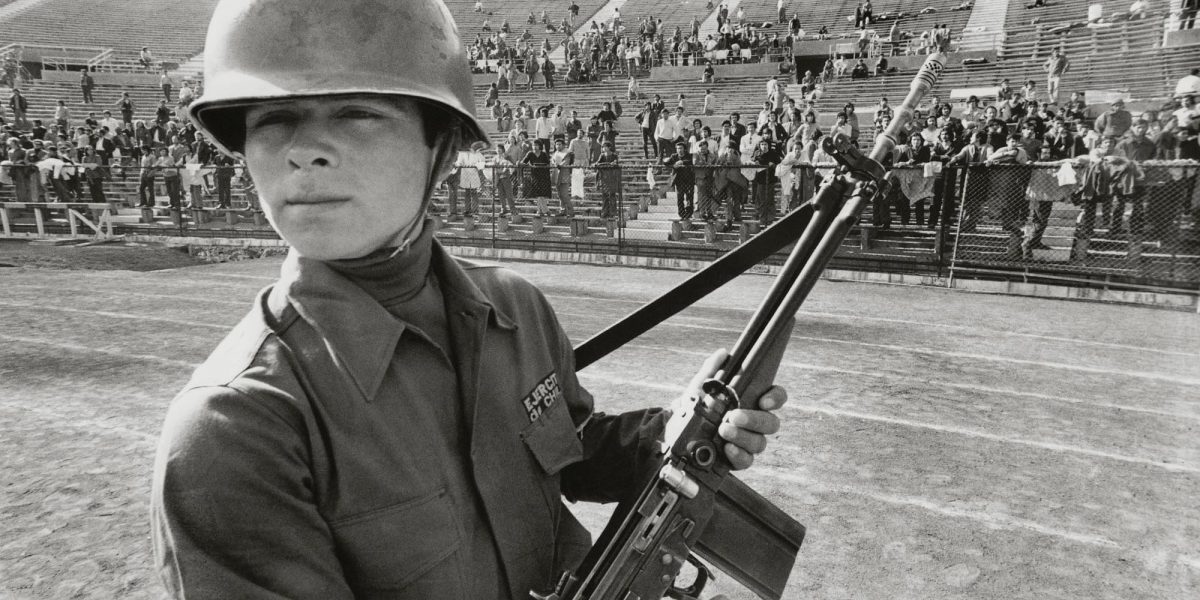

On the morning of September 11, 1973, the Chilean military made its move and announced its intention to overthrow the democratically elected government. Jets bombarded the Presidential Palace and Allende gave a final speech encouraging the continued fight for socialism before taking his own life.

The junta, led by Pinochet, engaged in a brutal crackdown on the left and the Chilean working class. Over three thousand people were killed and tens of thousands were arrested. Unions, media and democratic institutions were suppressed, if not banned. Thousands went into exile. The Chilean state became an experiment for neoliberal economic reform, with Western states and their economists using the Chilean economy as the model of privatization and deregulation. Although the dictatorship came to an end in 1990, Chile remains embroiled in the massive economic disparity these policies created and living under a constitution designed by despots.

The wave of protests in 2019 brought much hope to Chileans, many hoping that the radical economic and social promises of Allende’s election could be reignited. Left-winger Gabriel Boric’s election as president in 2021 and the radical constitutional proposals that emerged soon afterward saw similar excitement. However, the rank-and-file politics of the street had died down by the time Chileans voted on a brand new constitution and to little surprise the document was rejected. Boric now finds himself with little political clout to bring in even modest changes and the Chilean far right has re-emerged as a force to be reckoned with.

There are many lessons that we can learn from the coup and efforts in Chile since. The most significant is the limits of electoral politics in bringing radical change. Even the best-intentioned politicians will be cornered into the world of compromise and their world of backroom deals and negotiations cannot match the power and force of mass activity. Failure to learn this lesson continues to haunt the Chilean working class and the Chilean left.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate