2025 has been a devastating year in many ways. From the emboldening of the far-right, Trump’s tariffs plunging the global economy into crisis, the threat of nuclear war creeping closer, rising unemployment, to the complete destruction of Gaza, many long-brewing developments have become full-blown crises.

These events have been sharply reflected in the art that became available to us this year. Some of the best music, TV, film and books this year have tried to make sense of our descent into fascism and imagined what resistance could look like. While some works exposed the farcical nature of savage capitalism, other works tried to paint an alternative vision or a way out of this dystopian reality. At its best, art holds a mirror to our current moment, subverts it and even helps us chart a path out of it.

We asked Spring members to share what they loved reading, watching or listening to this year. We wanted to share short reviews of projects that really moved them and offered a sharp expression of the political moment. Here are some of the offerings we loved in 2025.

Mo (created by Mo Amer and Ramy Youssef)

Review by Carlie Macfie

After a nearly three year gap between seasons, the second and final season of Mo premiered on Netflix this past January. The show, co-created by and starring comedian Mo Amer, is a brilliant addition to the genre of semi-autobiographical scripted series by comedians. Admittedly, I am a sucker for the genre, which often blends humour, family dynamics and political observation. Mo goes above and beyond in every regard. It is laugh out loud funny, while simultaneously showcasing the humanity of not only displaced Palestinians but the broader undocumented migrant community in Texas.

Mo Amer, as the fictional Mo Najjar, is an undocumented refugee who has grown up strongly rooted in both his Palestinian identity and identity as a Texan. He tries to balance his family obligations, his relationship with his Catholic-Mexican girlfriend Maria, working while undocumented and the hoops he must jump through to get asylum after living in the US since childhood. The show includes damning portrayals of immigration detention facilities along the US-Mexico border, the infuriating bureaucracy of the US government, and the co-opting of Palestinian culture by Israelis (which proves inescapable even in Houston, Texas).

Alongside the poignant political commentary, the show also acts as a love letter to Houston and Mo’s real life connection to the city. It is clear that much of the humour and specificity of experiences can only be sourced directly from Mo Amer’s real life. Overall, the show’s success lies in its ability to show that the personal is political, but it can also be really funny!

With the current political landscape it feels radical that a Netflix show about a Palestinian Muslim family even exists, let alone one that so brazenly critiques US immigration policies and the occupation of Palestine by Israel. Come for the politics and stay for the touching, authentic relationships that have rarely been depicted so humorously on screen.

No Separation (MSPAINT)

Review by Spencer Bridgman

“We were never free, just cost effective.”

So begins No Separation, the 2025 12″ EP from synth-punk masters MSPAINT. Over fifteen minutes and five tracks, the Hattiesburg-based band consistently threads the needle between existential dread and inspiration. The thread that connects them is righteous anger, which guides vocalist Deedee as he rages against capitalism in all its manifestations—from climate change and genocide to the surveillance state and prison industrial complex.

When asked in an interview about the directness of the lyrics, Deedee replied that, “it’s all becoming quite literal to me… I don’t like dancing around stuff. At some point, you gotta say something’s on fire, something has to fall.”

Nowhere is this ethos more evident than on track three of the EP: ‘Surveillance’. The song starts with a sample from Marxist economist Richard Wolff explaining that, “slaves produce the surplus which the master gets, serfs produce the surplus which the lord gets, employees produce the surplus which the employer gets. It’s very simple.” Throughout the rest of the song, Deedee relays his own economics lesson—“margins for profit will benefit evil, structured around anything but the people”—and his own manifesto— – “break these cycles, break these chains, melt them down to mark their graves.”

In the hands of a lesser band, lines like this could come off as cringy, but MSPAINT’s greatest strength is that the sincerity of their message is matched by the intensity of their arrangements. The synths slap, the drums hammer, and the vocals pierce through the cacophony demanding your attention.

MSPAINT are not beating around the bush, there’s no time for that. Their message is very simple: the world is fucked up, the capitalists fucked it up, and only the people can fix it.

Shadow Price (Farah Ghafoor)

Review by Aadiyat Ahmed

In her debut collection, Shadow Price, Toronto based poet Farah Ghafoor takes aim at the central issues of the anthropocene and hits the mark. In this collection, Ghafoor is as much a researcher and documentarian as she is a poet. As the former, she lays out in clear and unvarnished terms the enormity of the climate crisis. Guiding us through the landscapes of history, from Ontario to India, she lays bare how it is a crisis born of colonialism and amplified by it still.

As the latter, Ghafoor proves herself as a lyrical chameleon. She draws on modes for the deeply introspective to the mythological and employs a variety of tones to portray the mood of this era. At times it is grim, capturing the alienation, the suffocation and (sometimes) sheer mundanity of life under capitalism. At other times, it is playful and satirical, for capitalism is not just alienating and suffocating. It is absurd.

This collection serves as a stark reminder of how much we’ve already lost to capitalism and a warning of how much we still have to lose. Wrapped in lyrics that are lively and irresistible, this is a call to action.

Exile (Chronixx)

Review by Rajean Hoilett

Chronixx’s Exile arrived quietly, without the rollout or spectacle that often accompanies a long-awaited release. That restraint feels intentional. Exile is the work of Chronixx, a central figure of the post-Roots generation, navigating a neoliberal Jamaica shaped by centuries of colonial extraction and ongoing exploitation by Canadian and U.S. imperialism.

Rooted in a historically anti-capitalist reggae tradition, Exile draws from the lineage of Bob Marley and Peter Tosh without nostalgia. Instead, it feels grounded, contemporary, and unmistakably working class. These are songs about endurance, dignity, and survival, not as abstract virtues, but as lived realities. Chronixx celebrates community and family while refusing to romanticize hardship. On “Never Give Up,” Chronixx frames struggle not as personal failure, but as a shared condition: “All of us been fighting since the day we were born.” Endurance here isn’t romanticized – it’s collective, inherited, and necessary in a world where giving up is rarely an option for working people.

Exile was released just weeks before Hurricane Melissa would devastate Jamaica, a coincidence that gives songs like “Hurricane” an unexpected weight. It’s a reminder that reggae’s spiritual language has always been tethered to material survival. In a moment of climate crisis disproportionately borne by the Global South, these songs feel less like metaphor than witness.

Elsewhere, the politics are explicit and material. “Market” confronts inflation, food insecurity, and the quiet cruelty of price hikes passed down to working people and farmers alike. “She blame it pon inflation… nuh wonder why the people dem a starve.”

The sound itself is political. Warm, restrained production and a refusal of spectacle mirror the album’s themes. This was the music playing for me in the lead-up to Spring’s Red October conference—less a soundtrack for triumph than one for collective endurance. In moments of crisis, music like this reminds us that struggle is shared, and that we are not alone.

Palestine 36 (dir. Annemarie Jacir)

Review by RBZ

Palestine 36—for all its compelling characters, bracing action sequences and narrative intrigue, plus astonishingly immersive visuals that transport us to the Arab Revolt of 1936-39 — clearly delivers a political message for this very moment. It is best watched in community with others (as some lucky Spring members did at a special Mayworks Festival screening), especially those others who can recognize its iconic, colorized archival images, its historical accuracy, and their own family stories in some of the events depicted.

The film obviously mirrors the settler-colonial brutality that Israel still inflicts on Palestine today. But it also enlarges the conversation by bringing into view the colonial and imperialist powers that have always backed the Zionist project, with divide-and-conquer tactics that they replicate across multiple territories. Filmmaker Annemarie Jacir intelligently highlights major social cleavages between urban denizens vs. rural farmers, upper-class elites vs. the poor and working-class, and collaborationist vs. oppositional, institutional vs. revolutionary responses to the British. At the same time, she portrays labour and internationalist solidarity, as well as community ties that hold across religious and ethnic differences. Women play particularly important roles in the resistance.

At the end of the day, Palestine 36 reminds us that, amidst the swell of social conditions not of our own making, together we can still make history. Each of us chooses whether or not to donate our jewels, betray our neighbors, accept payments from the powerful, lobby the government, even take up arms. One way or another, we all take our places in the vast tapestry of humanity during times of great injustice—let us act, then, on the right side of history

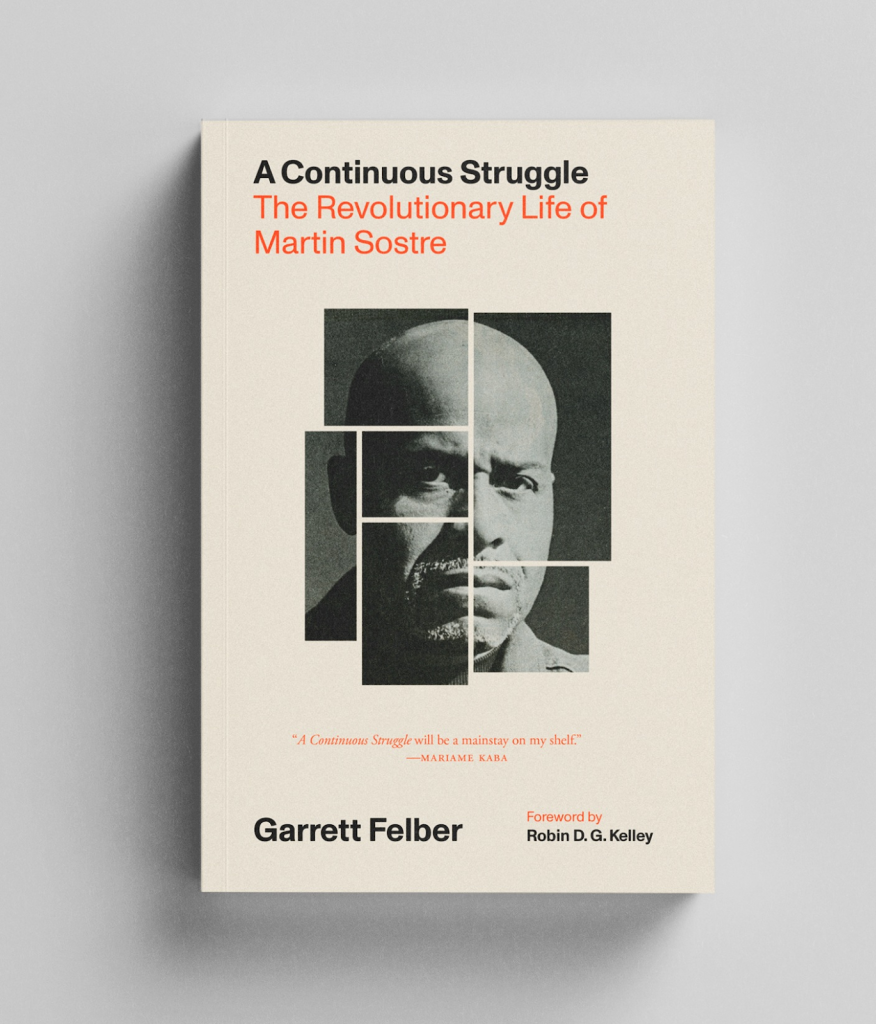

A Continuous Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Martin Sostre (Garett Felber)

Review by Eric Shatosky

A Continuous Struggle serves as the sole biography that depicts the life of Martin Sostre, a revolutionary prisoner, abolitionist and Black anarchist whose political praxis served as one of the primary embodiments of the political transformation of criminalized people during the Black liberation movement. Sostre was one of the most famous political prisoners in the United States, next to Huey Newton, George Jackson, and Angela Davis, before fading from the public consciousness leading up to the later 20th century. During his time incarcerated, Sostre established himself as one of the most pragmatically effective prisoner lawyers that advanced the rights of those most vulnerable to state oppression. His story teaches us not only when, but how to confront state oppression through the utilization of legal mechanisms to further the emancipation of incarcerated people. It was because of Sostre (alongside his peers) that due process, the religious practice of prisoners, as well as the application of the First Amendment to challenge prison conditions are cemented into legal doctrines that arose from the progressive social movements of the 1960s.

Felber beautifully illustrates how Sostre’s intersectional consciousness develops over his life, from his internationalist recognition of Palestinian sovereignty to his devotion to feminist liberation, which eventually culminated into his personal identification as a revolutionary. Perhaps most of all, Sostre further bridged the divide between prisoners rights and human rights, showcasing how incarcerated people remain the compass of our continuous struggles.

The Book of Records (Madeleine Thien)

Review by Robyn Letson

My favourite novel of the year, Madeleine Thien’s The Book of Records, is difficult to do justice to in summary, but here’s my best attempt:

Lina and her father arrive at a vast enclave of buildings called the Sea, a self-organized stopover for migrants. They are fleeing climate collapse in Foshan, China, and have become separated from Lina’s mother, brother and aunt. The Sea is a surreal place that seems to defy the laws of time and space—evocative of the work of Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges. While most people come and go quickly, Lina and her father, too ill to travel, make a home there. Lina has three volumes from her brother’s mail-order book series, “The Great Lives of Voyagers”—one on 20th century German writer Hannah Arendt, one on 16th century Portuguese philosopher Baruch Spinoza, and one on 8th century Chinese poet Du Fu. Lina befriends three somewhat mysterious neighbours, who tell her stories that the books leave out. What ensues are accounts of exile, migration, struggle, and survival—and how these experiences shaped the ideas of each writer.

Thien’s novel is totally absorbing—ambitious in imaginary and historical scope while grounded by a deep belief in human dignity and solidarity. It reminds me of other recent works of radical speculative fiction: An Ocean of Minutes by Thea Lim and Everything for Everyone by ME O’Brien and Eman Abdelhadi.

And in case you need another reason to pick up this book, Thien, a former Giller Prize winner, has been active in the No Arms in the Arts Campaign. In an open letter to the Giller Foundation last year, she requested that her name, image and work be removed from their website and all related promotional materials.

The Book of Records is a beautiful novel by a principled and gifted writer. Seek it out!

Sinners (dir. Ryan Coogler)

Review by Josh Frame and Deena Newaz

Much more than just a film about vampires, Sinners is about music, race, identity, and the experience of loss and uprootedness in America’s settler colonial melting pot. The film explores these themes through blues music—a genre born out of Black resistance and later commodified in commercial rock and roll music—-and says something important about cultural rootedness vs. assimilation, and who gets to participate in the settler colonial project.

Each character sits somewhere between rootedness and assimilation. The identical twins Smoke and Stack mirror each other in their relationship with their cultural roots. Smoke is the closest to his roots and ancestors along with his wife Annie, incidentally the first to recognize the evil when it appears in the movie. The main star of the film is Sammie, a preacher’s son and a blues prodigy who is taken under the wing of the twins. Sammie’s connection with his roots and ancestors is palpable as he resists the Protestant culture that has consumed his father and clings on to his guitar till the end. His soulful voice takes a life of its own in a stunning montage scene where we witness the evolution of blues music, born out of African music and the displaced Black population that brought it to the Americas.

On the other hand, we have Remmick the vampire. It is the trope of Remmick’s vampirism itself which represents the suffocating drive to assimilate everything into the settler colonial project—to live in “harmony,” as he puts it. But harmony for whom? We learn throughout the movie that Remmick is in fact Irish and a similarly displaced person. The difference is that Remmick, and white people generally, can gladly assimilate into a homogeneous American melting pot because it was designed for them. This of course is not true for Black people living in the segregated US south, forcing the viewer to think about upon whose terms assimilation occurs.

But the real question the movie asks is, “What have we all lost?” Throughout, the vampires seek to turn as many people as possible and absorb their knowledge and cultural heritage. However, all they get is a doomed attempt to feel a connection to something authentic—flat homogeneity instead of true communion. In a time of accelerating globalized capitalism, where our consumer choices are more numerous than ever, we must at least ask ourselves the same question.

Black Panther: The Intergalactic Empire of Wakanda (Ta-Nehisi Coates)

Review by Rajean Hoilett

This year, I read volumes 6–9 of Black Panther: The Intergalactic Empire of Wakanda by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Though the series was published in 2021, it feels especially resonant now, as questions of empire, rebellion, and liberation continue to shape our political moment.

Using time travel, Coates imagines a future where Wakanda’s technological power has hardened into an intergalactic empire, ruling distant worlds through conquest, extraction, and slavery. Wakanda is stripped of its exceptionalism and treated as history repeating itself. The story rejects the comforting fiction that advanced technology or benevolent leadership can redeem imperial power. Empire, regardless of its origins, produces exploitation as a system.

The heart of this arc lies not in T’Challa’s moral crisis, but in the growing, worker- and slave-led rebellion that challenges the empire from below and requires sacrifice. Liberation here is not the result of reform or remorse, but of collective struggle by the oppressed themselves.

As a work of Afrofuturism, Intergalactic Empire of Wakanda does more than escape into speculative worlds. It uses imagination to confront real material questions: how power consolidates, how empires justify themselves, and how resistance is born. By stretching our sense of history and possibility, the series offers a sharp reminder that the future is not guaranteed: it is fought for.

No Other Choice (dir. Park Chan-Wook)

Review by Tahira Newaz. Contains spoilers.

2025 has been a year where political cinema felt less like an option and more like a necessity to reflect the struggles of our time. Becoming a member of Spring has deepened my appreciation for the radical arts and the role they play in the revolution by providing moments of joy, reflection, and even inspiration. Among the many powerful films this year, Park Chan-Wook’s No Other Choice stands out as both poignant and delightful, making it a perfect watch for the holidays.

No Other Choice, adapted from Donald E. Westlake’s 1997 novel The Ax, is a comedic social satire anyone touched today’s precarious job market can identify with. Man-Su (played brilliantly by Lee Byung-hun of Squid Game) is a loyal paper company employee of 25 years who gets fired and finds himself with ‘no other choice’ but to eliminate his competitors for a job. What begins as desperation spirals into dark absurdity. After 18 months of rejection and watching his dignity erode, Man-Su creates a fake company to lure and kill his rivals, hoping to become the only candidate left standing.

Park’s critique of a system where self-worth is intrinsically connected to the ability to create capital and the dehumanization of mass layoffs is sharp and direct. Park exposes South Korea’s stark inequality and gender roles, weaving in Man-Su’s fear of ending up like his father, a pig farmer who died by suicide after losing his livelihood. Man-Su embodies the devastating reality of being fired in your 50s; not just becoming unqualified for anything else, but the deeper emotional toll of shame and alienation. The film exposes a systemic paradox where we live in a world that demands we work while subsequently eliminating our opportunities to do so.

While an extreme take, the film’s premise is prescient today, as late-stage capitalism has created a structure of pitting one worker against another rather than the system itself. We glimpse into the future when Man-Su does get hired as the only worker at a factory where everyone else has been replaced by AI. Man-Su gets the job, but he loses all his coworkers, working in solitude and living in a house with the remains of his victims; a metaphor for what capitalism offers.

Perhaps, Park himself is fearful of being replaced with AI one day, and had no other choice but to create this masterpiece.

Did you like this article? Help us produce more like it by donating $1, $2, or $5. Donate